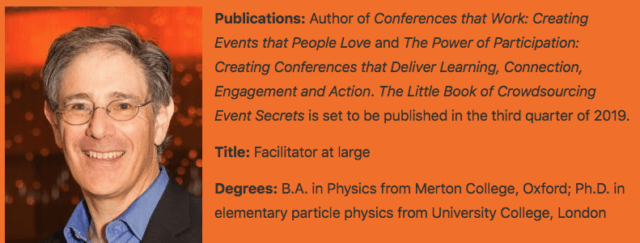

Q&A with Adrian Segar on Crowdsourcing

This (slightly edited) interview by JT Long — a Q&A with Adrian Segar on Crowdsourcing — appeared in the March 2019 issue of Smart Meetings Magazine.

What led to writing the book, Conferences That Work?

I invented the format by accident 26 years ago when there were no expert speakers to invite to a conference on administrative computing issues in small schools. We needed a format that would allow a room of strangers to learn about each other and the issues we were interested in by using the expertise in the room.

I asked people, “If this conference could be amazing for you, what would it be about?” Then I built a program around those topics, with people in the room leading impromptu sessions. Often, the results are unexpected. The sessions are not polished; there is no PowerPoint. Often it is more like a discussion than a presentation, but that is why it is effective. My research shows that asking in advance doesn’t work. At traditional conferences with fixed programs set in advance, at best half of the sessions offered are what attendees want.

That participant-driven conference is still going as a four-day program, with sessions generated over the first half-day.

I discovered that people love the format, and that led to writing the book 10 years ago. I was an amateur in the meeting industry, and that led to some mistakes, but it also gave me a fresh perspective at a time when meeting design wasn’t really a “thing.”

What has been the reaction in the market?

A lot more people are using the peer-conference principles to varying degrees, and I have facilitated conferences for groups, such as PCMA Convening Leaders. Just-in-time learning gives people what they need right now.

This encouraged me to write a second book in 2105, The Power of Participation: Creating Conferences That Deliver Learning, Connection, Engagement, and Action, which contains a comprehensive tool chest of conference and sessions techniques that meeting planners and presenters can use to improve learning, connection, engagement, and outcomes at their events.

Why did you decide it was time to write a third book?

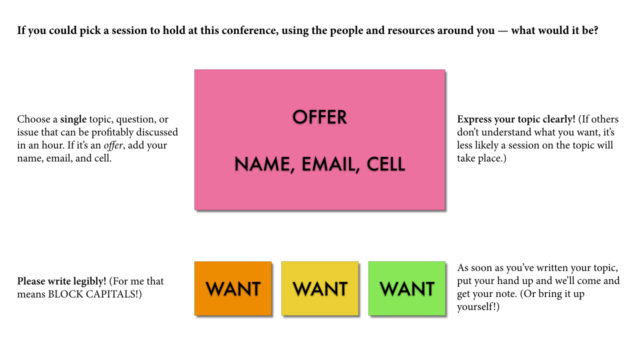

The Little Book of Event Crowdsourcing Secrets is about how to create conferences that turn into what participants actually want and need. People love being heard and having their needs met. Crowdsourcing allows you to do that.

I wanted to expose more people to these valuable formats. I am just one person doing this work, and I wanted to get them out into the world.

Why Conferences Need to Change

Lectures are a terrible way to learn. They are a seductive meeting format because they provide an efficient way of sharing information. However, they are the least effective way of learning anything. Over time, we rapidly forget almost everything we’ve been told. But when we engage with content, we remember more of it more accurately and longer.

Everyone has expertise to share. Instead of limiting content to a few “experts,” peer conferences uncover and tap the thousands of years of experience in the room.

Informal education rules. Today, only about 10 percent of what we need to know involves formal classroom teaching. The other 90 percent is informal—a combination of self-directed learning, experiential learning on the job, and learning at conferences with our peers.

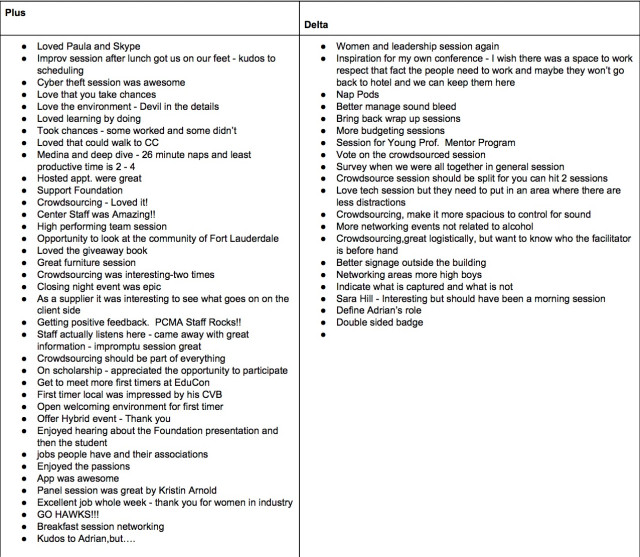

How do you know if a crowdsourced event is successful?

You can feel the energy level. By definition, these sessions are about things people want to talk about, so how can you lose? If you try to predict what people want to talk about six months before, it won’t be accurate.

How can event professionals integrate your techniques into an event?

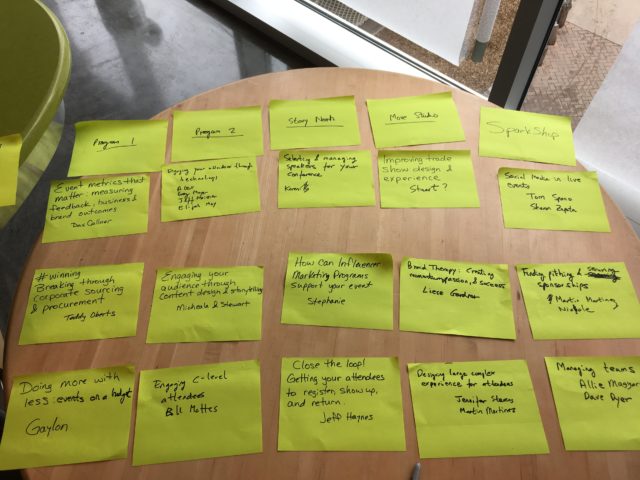

One way is to set aside a block of time—a couple of hours for example—to do sessions that are crowdsourced during, say, lunch, the day before.

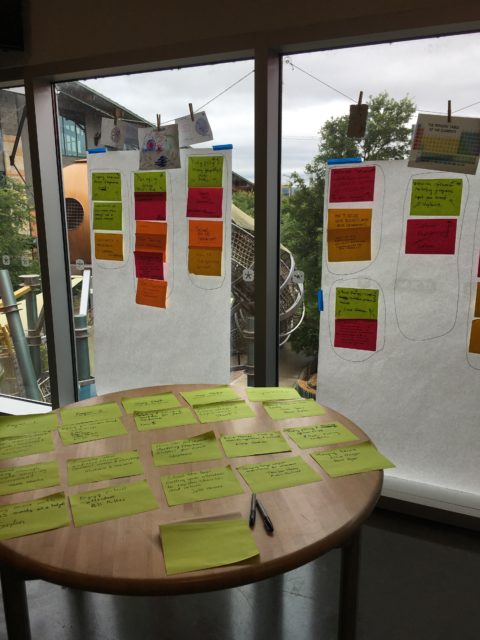

One of the beauties of the sticky notes display is if you put up an issue and a session doesn’t result from it, attendees can connect with the one other person at the conference who really wants to talk about the topic, and that can make the whole conference worthwhile. It is a great way to meet the people who are right for you.

What do people need to watch out for when planning a crowdsourced event?

The biggest mistake is making it a conference track instead of committing across a time block. Most people have not experienced these formats and they might not choose it, even if they would enjoy it if given a chance. Then the conference organizer concludes people are not interested. Pick a period of time for the crowdsourced sessions and have nothing else scheduled. Then meeting stakeholders generally keep crowdsourced sessions in the program and extend them over time.

You have to create a safe environment for people to share. It can feel risky to talk about a challenge at work. That is why you need to agree to rules at the beginning so that people feel comfortable. Otherwise, you won’t get the juicy stuff.

“Design is how it works” is the favorite thing Apple software engineer

“Design is how it works” is the favorite thing Apple software engineer  How can we design for powerful connection and learning at large meetings?

How can we design for powerful connection and learning at large meetings? Do your conference programs include pre-scheduled sessions you belatedly discover were of little interest or value to most attendees? If so, you’re wasting significant stakeholder and attendee time and money — your conference is simply not as good as it could be.

Do your conference programs include pre-scheduled sessions you belatedly discover were of little interest or value to most attendees? If so, you’re wasting significant stakeholder and attendee time and money — your conference is simply not as good as it could be.

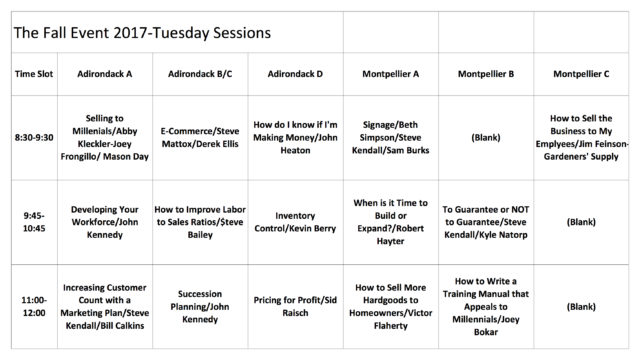

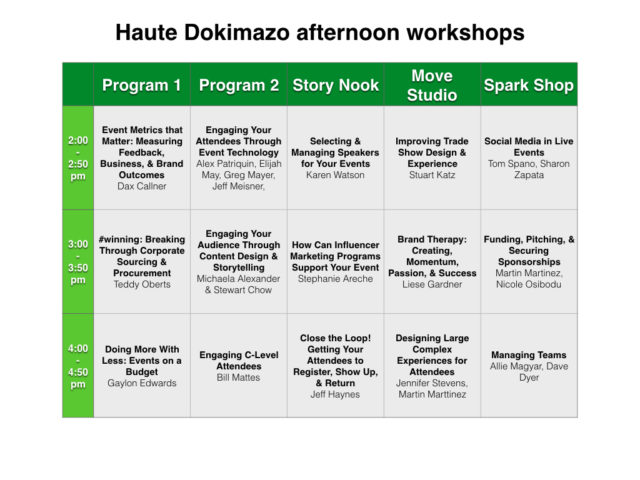

How do we build conference programs that attendees actually want and need? Since 1992 I’ve experimented with multiple methods to ensure that every session is relevant and valuable. Here’s what happened when I incorporated dot voting into a recent two-day association peer conference.

How do we build conference programs that attendees actually want and need? Since 1992 I’ve experimented with multiple methods to ensure that every session is relevant and valuable. Here’s what happened when I incorporated dot voting into a recent two-day association peer conference.

Here’s a 22-second video excerpt of the dot voting, which was open for 35 minutes during an evening reception.

Here’s a 22-second video excerpt of the dot voting, which was open for 35 minutes during an evening reception.