Six fundamental ways to make a better conference

The other day, a client booked an hour with me to discuss ways to improve their conference. Not much time, but enough for us to uncover and for me to suggest plenty of significant improvements.

Reflecting on our conversation afterward, I realized that all my recommendations involved six fundamental processes that, when implemented effectively, can make any conference better.

- Using participant agreements.

- The Three Questions.

- Pair/trio share.

- Fishbowl.

- A personal introspective.

- A group spective.

So here’s a brief introduction to each of these core processes. Each section includes suggested links and resources to learn more.

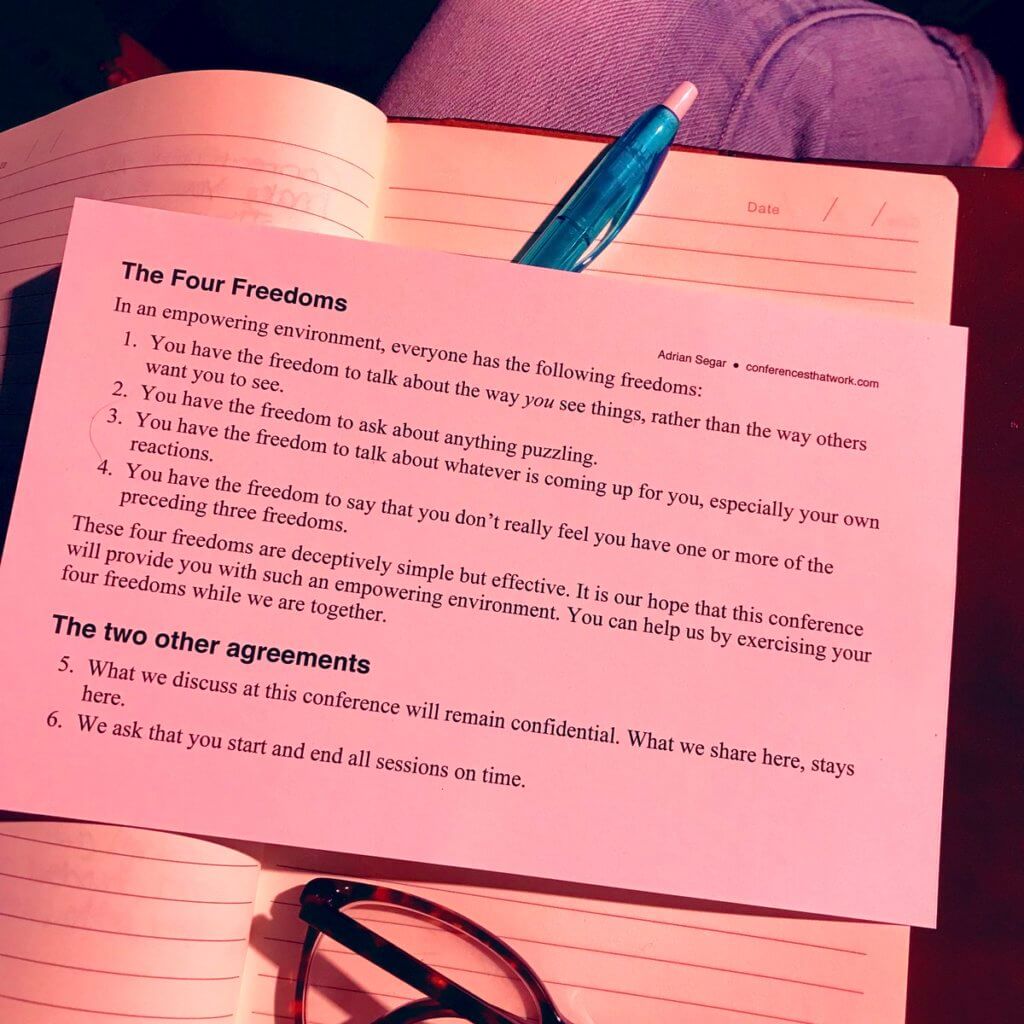

Using participant agreements

Meeting ground rules, covenants, or agreements. Whatever you call them (I’ve used all three terms), explicitly naming and asking participants to commit to appropriate agreements at the start of a meeting fundamentally improves conference environments.

Participant agreements help to create an intimate and safe conference environment. They set the stage for collaboration and participation because they give people permission and support for sharing with and learning from each other

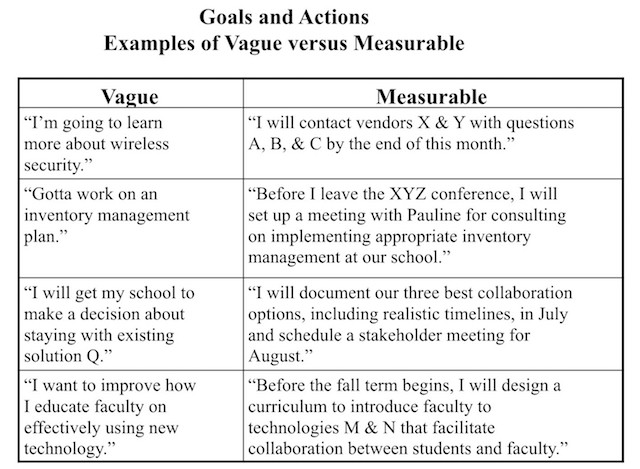

I’ve used the six pictured above for many years. You can read more about creating attendee safety and intimacy through agreements—and the benefits for your meetings—in Chapter 17 of The Power of Participation.

Creating agreements at the start of a meeting takes five minutes!

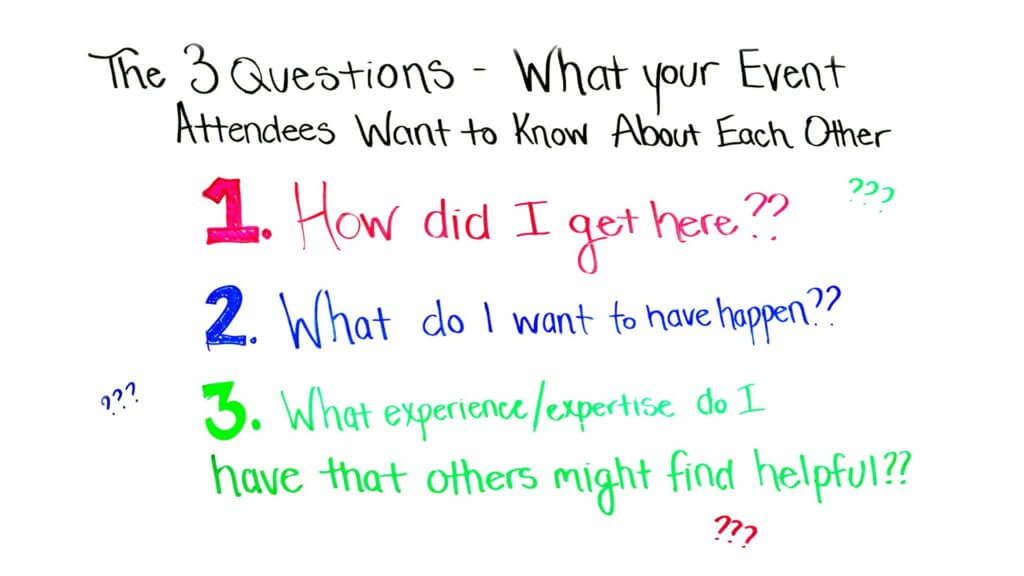

The Three Questions Ultimately, there are three key things that conference attendees want to know about each other. As this post explains, they want to know about:

Ultimately, there are three key things that conference attendees want to know about each other. As this post explains, they want to know about:

- Attendees’ relevant pasts that bring them to the meeting;

- What people personally want to learn and happen at the meeting; and

- The valuable experience and expertise that’s available from others in the room.

I’ve covered the value and how to run The Three Questions in all three of my books, but the latest and most up-to-date description is in Chapter 18 of Event Crowdsourcing.

And check out this video (transcript included) where I explain The Three Questions with the help of my friends at Endless Events.

The Three Questions typically take 60-90 minutes. When you add it to a one-day or longer conference, it will significantly deepen participant connections made and strengthened during the event that follows.

Pair/trio share

Any conference session that doesn’t regularly use pair share (or trio share) is missing out on the simplest and easiest tool I know to improve learning and connection during the session. (Okay, if you’re running lightning talks, Pecha Kucha, or Ignite, you get a pass.)

The technique is simple: after pairing participants up and providing a short period for individual thought on an appropriate topic, each pair member takes a minute in turn to share their thoughts with their partner. Read this post to learn why you should use pair share liberally throughout an event. For more details, refer to Chapter 38 of The Power of Participation.

Fishbowl

Every good conference includes participant discussions (aka breakouts). The single most effective way to facilitate a productive discussion that prevents anyone from monopolizing the conversation is the fishbowl format. (Which you can also use online.)

[TIP: You can use fishbowls to great effect in panel discussions too! Here’s how I do it.]

[BONUS TIP: There’s a fishbowl variant, the two-sides fishbowl, which is great for exploring opposing viewpoints in a group.]

See this post’s conclusion for one more variant!

Fishbowls are flexible formats that can be adapted to the available time and the number of participants. Learn more about them in Chapter 42 of The Power of Participation.

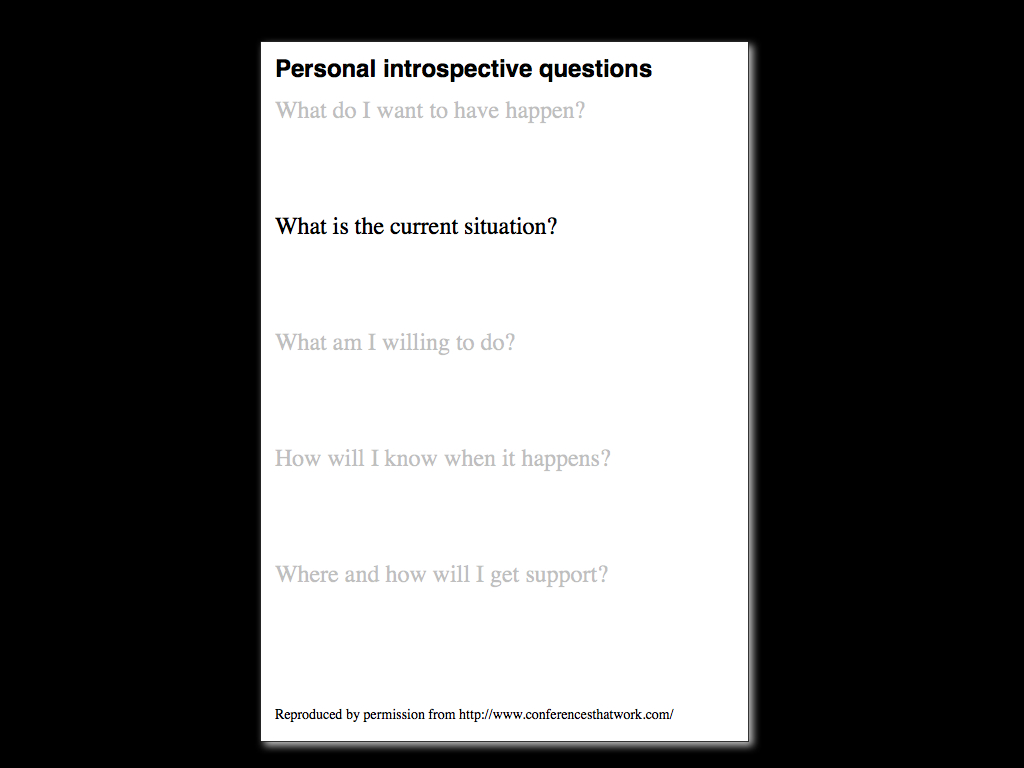

A personal introspective

Refer to this introduction, or Chapter 57 of The Power of Participation, for complete details.

A group spective

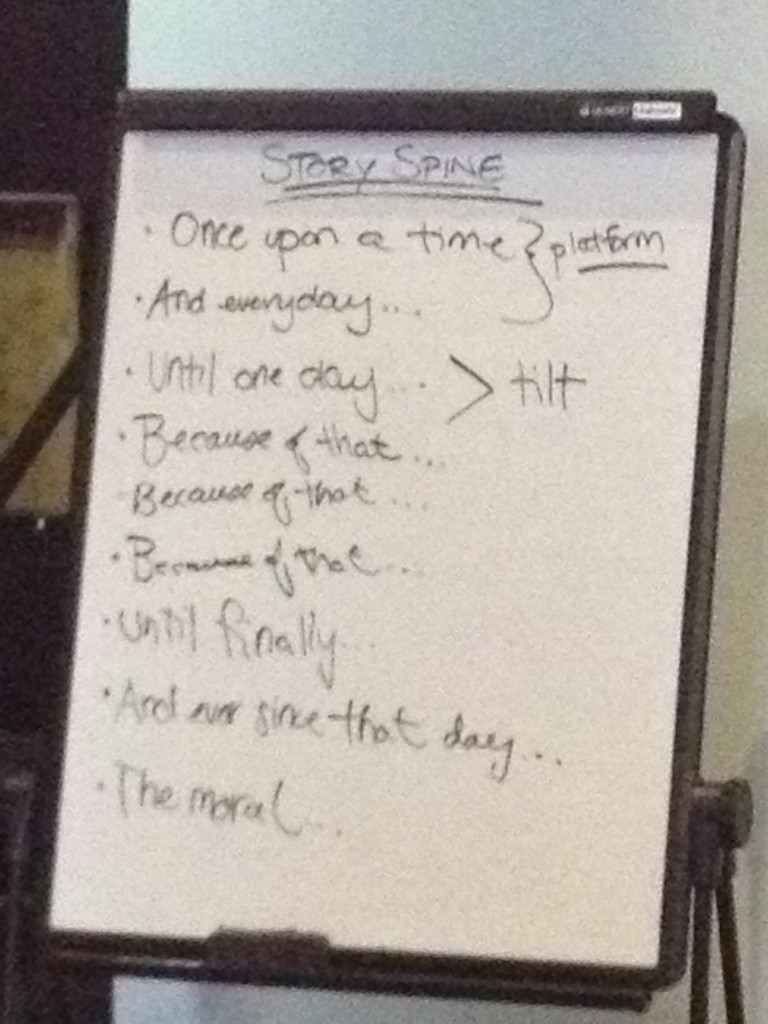

Every conference I design and facilitate has a final session that I call a group spective. The personal introspective described above allows participants to review what they have personally learned and to determine what they consequently want to change in their lives. A group spective provides a time and a place to make this assessment of the past, present, and potential future collectively.

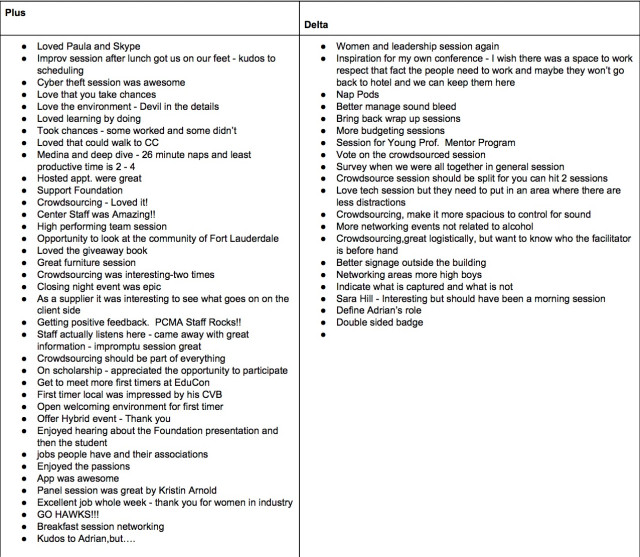

The design of a group spective depends on the goals and objectives of the preceding event. These days, I invariably start with a beautifully simple technique, Plus/Delta (see Chapter 56 of The Power of Participation), in which participants first publicly share their positive experiences of the conference. When that’s done, they share any changes they think would improve the event if it were held again.

Plus/Delta is an elegant tool for quickly uncovering a group’s experience of a conference. I’ve run them for hundreds of people in thirty minutes. (Some groups take longer; your experience may vary!) A Plus/Delta usually has an immediate emotional impact, drawing the group together right at the end of the event.

For more details, refer to this introduction or Chapter 58 of The Power of Participation.

[TIP: A variant, action Plus/Delta, is a great tool for a group to determine and commit to group action outcomes uncovered at a conference.]

Conclusion

It’s best to think of these six core processes as building blocks that can be used in multiple ways. Combining them appropriately enables you to create a customized, optimal process to meet different goals. A great example is using two pair shares around a fishbowl to create what I call a fishbowl sandwich: an incredibly effective way to create very large group discussions around a meaty topic.

It’s also helpful to see these processes as parts of the conference arc, which is how I envision the overall flow of a participant-driven and participation-rich meeting.

One final point. When appropriately incorporated into a well-designed meeting, these six core fundamental processes can make any conference better. However, for maximum effectiveness, it’s essential to use them in a consistent manner.

For example, participant agreements are often useless, if not counterproductive, if conference and session facilitators don’t support them. Similarly, telling attendees they’ll have the opportunity to participate in their learning and then feeding them a diet of broadcast-style lectures will not be well received. In fact, competent facilitation is a prerequisite for these processes to be successful. (Yes, I’m here to help 😀.)

The meeting is over. Did anyone learn anything? And how would you know?

The meeting is over. Did anyone learn anything? And how would you know? How can we design for powerful connection and learning at large meetings?

How can we design for powerful connection and learning at large meetings?

Understanding the psychology of motivation can help us create better event outcomes. I’ll illustrate with a story about unusual traffic on this very website…

Understanding the psychology of motivation can help us create better event outcomes. I’ll illustrate with a story about unusual traffic on this very website…