Five ways explicit communication improves meetings

1—Tell attendees how your meeting socials will be social!

Want to make your meeting “socials” actually social? Don’t just throw a party with loud music. Like many attendees, I love to dance (when the music’s right). But some people don’t; they want to socialize by talking with others. And most people don’t want to dance non-stop for an entire party.

So attendees need somewhere to talk. And unless they possess excellent hearing, conversing with a colleague while Heroes plays from a monster speaker ten feet away is, well, challenging.

I’ve been at too many event parties where loud music was inescapable. They probably contributed to my current need for hearing aids in group settings. These days I often pass on event parties because I can’t hear anyone over the music.

Meeting planners can make me (and many other attendees) happier by giving us somewhere quiet nearby where we can escape and talk whenever we want. Many events do this—but few tell attendees they have the option!

A little explicit pre-party communication will improve your meeting. “Hey, if you want to talk as well as party, take a few steps and enjoy the comfy sofas in the quiet and elegant LuxeTime lounge!” will be music to many ears.

I’ll be there!

TIP: Many people love to dance but don’t want to get any deafer. The solution: provide (sponsor branded?) earplugs! And, tell attendees in advance they’ll be available.

2—Provide and promote places for people to talk

Conference stakeholders who are serious about maximizing connection at their events provide plenty of places besides the hallways to talk and network. Whenever possible, include appropriate furnishings to make these spaces attractive places for people to connect. Then improve your meeting by documenting, promoting, and encouraging people to use your venue’s quiet spaces.

Think creatively about how to do this. For example, session rooms are often vacant at times. Distribute a “quiet meeting spaces” schedule to attendees so they know where and when they can arrange meetings or go on the spur of the moment. And make sure your room signage advertises these spaces to attendees walking by.

3—Frame exemplary interaction between sponsors/exhibitors, and attendees

Sponsors and exhibitors want to meet potential new customers and strengthen existing relationships. Attendees typically want to find suppliers who can solve current problems and meet their needs. For this to happen, these groups need to interact, typically at trade shows, sessions where suppliers lead or contribute, and meeting socials.

We’re all familiar with this dance, but some meetings implement it better than others.

Attendees, especially when they comprise a minority, can be profoundly irritated by overexposure to suppliers. Examples include sessions that are primarily product or service pitches and socials where attendees have little opportunity to talk alone with each other. Sometimes attendees want “attendee-only” sessions where they can talk frankly about supplier experiences.

Getting win-win interactions between attendees and suppliers requires explicit communication with both groups before or at the start of the event.

What suppliers need to hear

Clearly explain to suppliers before the event, that they’ll do best if they don’t aggressively pitch their products and services. Smart suppliers already know this, but there always seem to be some who haven’t gotten the message. In particular, ban sales pitches on stage. Require suppliers who are presenting to describe in advance how their content will educate session attendees appropriately.

If the event is small (and most meetings are small meetings) consider holding a short session for all tradeshow vendors, allowing each supplier a minute at most to pitch their offerings to attendees. Encourage attendees to be there by holding the session right before the tradeshow opens. I’ve found that suppliers and attendees appreciate such sessions and they reduce the likelihood that annoying pitching will occur at other times.

What attendees need to hear

Attendees may really appreciate some meeting sessions that exclude suppliers so participants can have candid discussions about their supplier choices. If your event includes such sessions, let attendees know in advance! (And, of course, make arrangements to ensure that suppliers don’t attend.)

4—Improve the effectiveness of technical checks

By now, we’ve all had to suffer online presenters who:

- Look terrible; or

- Are largely inaudible; or

- Never show up due to “technical difficulties”.

Event producers can minimize these serious defects by holding technical checks beforehand. If only it was so simple!

On a recent weekly Event Tech chat led by Brandt Krueger, we discussed the knotty problem of getting online presenters to do technical checks before the event. Common issues were presenters who:

- Ignore or don’t show up for the appointment.

- Turn up and inform you that their session’s equipment/location, won’t be the same as what they’re currently on with you.

- Say “Don’t waste my time — I’ve done this a million times before!”

- Are eager to be “checked” but then want an hour of advice on their setup.

How can explicit communication help with these issues?

- To minimize no-shows, put the requirement for a tech check in presenter contracts.

- Also include in the presenter contract that the tech check must be held with the same equipment & location the presenter will be using at showtime. (Yes, sometimes this is impossible, but at least the production crew can be warned in advance and schedule extra time to test before the presenter goes live.)

- For the self-proclaimed experts, tell them it will only take a few minutes (if everything is fine). Tell them that you want them to be seen and heard at their very best, and you’re here to help. Be prepared, if anything needs fixing, to quickly share what the presenter can do. (Brandt showed us a rule of thirds overlay with an oval for the ideal head position to speedily and gently improve a presenter’s video.)

- And for the newbie presenter who wants you to give a free lengthy consult, let them know you’ve only got, say, 15 minutes for the appointment.

There are no guarantees, but explicit communications like these will likely make your online event run smoother.

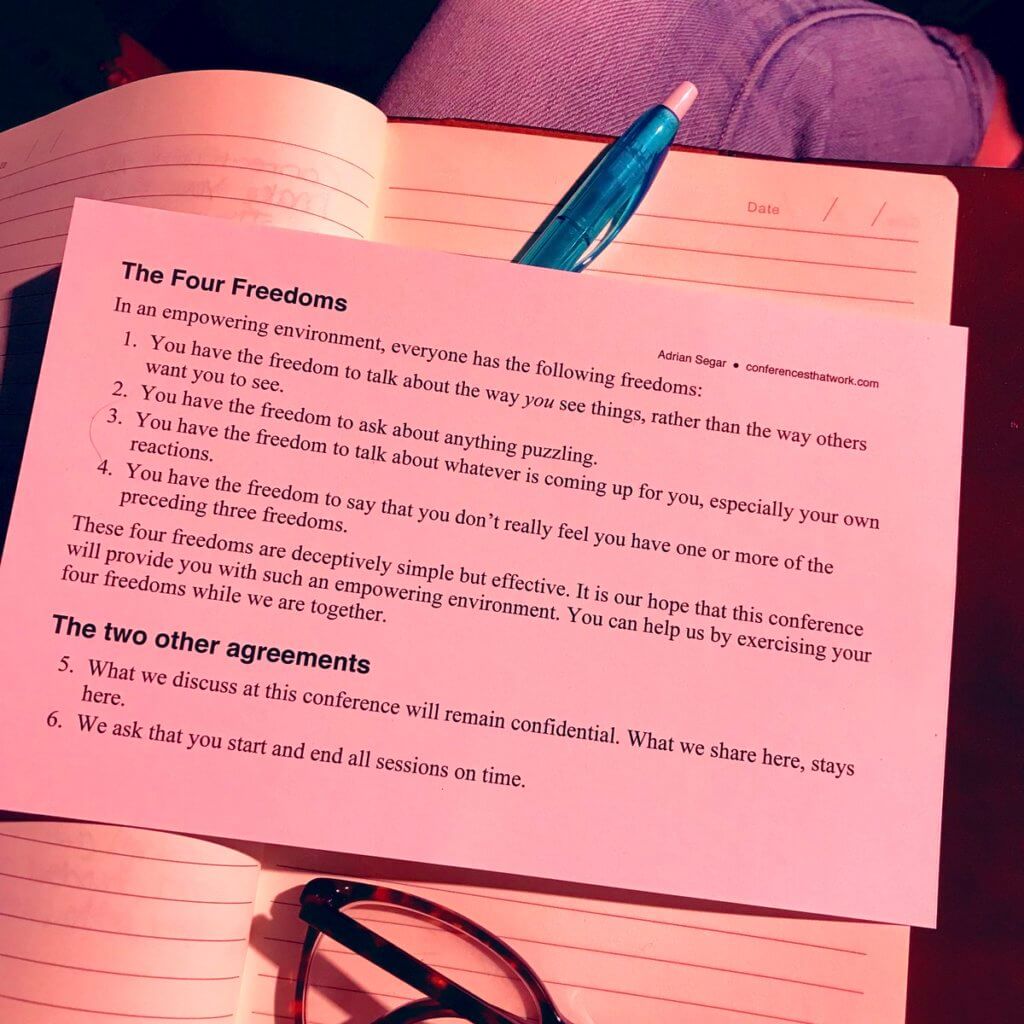

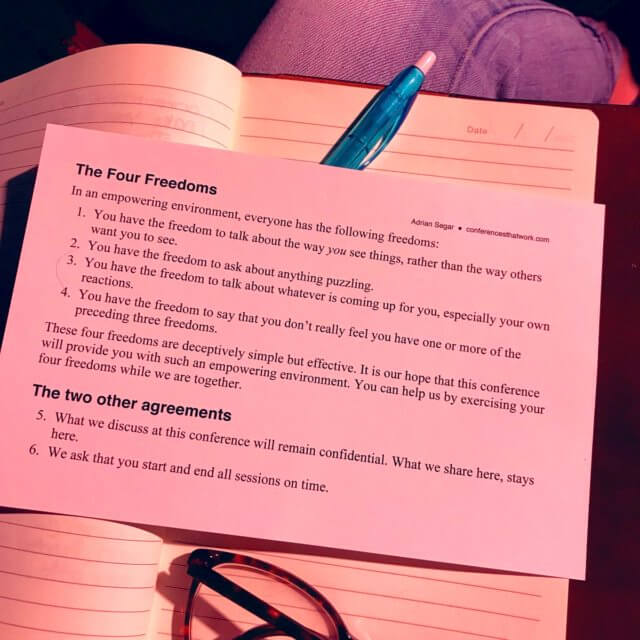

5—Include explicit meeting agreements

I’ve left the best until the end. The most important way to improve meetings with explicit communications is by creating explicit attendee agreements (aka covenants or ground rules) at the start of an event.

I’ve written extensively about the importance of agreements and how to use them in my books and on this blog (1, 2, 3, 4, 5). Check out these resources to learn more.

But wait, there’s more!

Stay tuned for a post on the mechanics of explicit communications next week!

HT to Brandt Krueger and Glenn Thayer for sparking some of the ideas in this post in a couple of weekly Event Tech chats! (Join us on Zoom, Fridays, noon Eastern Time. We’re a friendly bunch!)

Much of the learning that occurs during a traditional conference is wasted because participants don’t have the time or opportunity to consolidate and integrate personal learning into their future life and work. Though a personal introspective takes about an hour to run, it’s the single best way I know to maximize the learning and future outcomes of an event. I recommend you use one at the end of any multi-day conference.

Much of the learning that occurs during a traditional conference is wasted because participants don’t have the time or opportunity to consolidate and integrate personal learning into their future life and work. Though a personal introspective takes about an hour to run, it’s the single best way I know to maximize the learning and future outcomes of an event. I recommend you use one at the end of any multi-day conference.

Tired of meetings that don’t end on time? Who isn’t? Things were bad enough when we held our meetings in person. Now so many meetings are online, it’s easy to saddle remote workers with back-to-back meetings. When one overruns, you’re late to the next one. Hey presto, your tardiness snowballs! (And, no,

Tired of meetings that don’t end on time? Who isn’t? Things were bad enough when we held our meetings in person. Now so many meetings are online, it’s easy to saddle remote workers with back-to-back meetings. When one overruns, you’re late to the next one. Hey presto, your tardiness snowballs! (And, no,

How can you support a community online? Over the last few weeks, I’ve run numerous online

How can you support a community online? Over the last few weeks, I’ve run numerous online

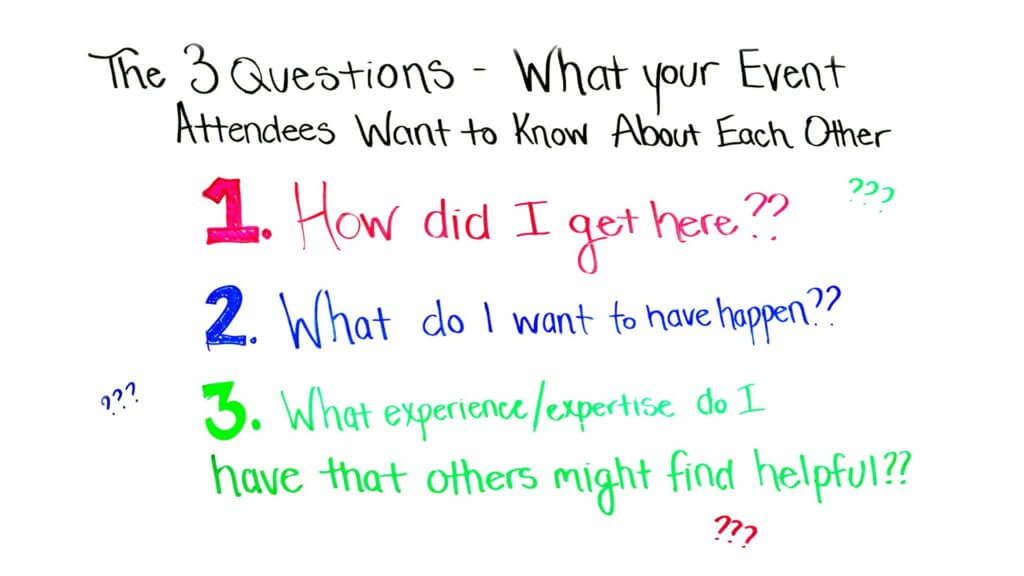

What might leadership for meetings look like?

What might leadership for meetings look like? When we enable people to meaningfully connect at a meeting, something extraordinary happens. We transform a conference from an impersonal forum for information exchange to a place where people feel they matter: their views, their experience, and their ability to contribute become seen.

When we enable people to meaningfully connect at a meeting, something extraordinary happens. We transform a conference from an impersonal forum for information exchange to a place where people feel they matter: their views, their experience, and their ability to contribute become seen. Professional, trade, and public interest associations are significant businesses. In the United States alone,

Professional, trade, and public interest associations are significant businesses. In the United States alone,  You can spend five minutes at the start of your events doing something that will significantly improve them. Something I bet you don’t currently do. You can improve your events with covenants. To understand why including group covenants will make your meetings better, let’s eavesdrop on what’s going on in your attendees’ heads…

You can spend five minutes at the start of your events doing something that will significantly improve them. Something I bet you don’t currently do. You can improve your events with covenants. To understand why including group covenants will make your meetings better, let’s eavesdrop on what’s going on in your attendees’ heads…