You can click on the graphic above to watch the video of our engaging conversation. but I admit that I generally prefer to read transcripts of talking heads videos. So I took the time to create one for what I think was an incredibly informative conversation. Here it is—enjoy!

Paul Nunesdea: Hello, dear viewers, this is a soft start of our third episode in 2024 of Talk to Your Meeting Doctors. As you probably know by now, we are pleased to entertain today our guest speaker Adrian Segar. He will be talking about his work in a few minutes, but it’s great to be here with you again. Martin, welcome!

Martin Duffy: Well, good afternoon. Lovely to meet you, Adrian. Perhaps people didn’t catch it at the very start, but Adrian, you were just explaining that you’re about 50 years in the States.

Adrian Segar: Yes, I spent the first 25 years in England and began my first career there, fell in love with Vermont to my complete surprise on only the second time I ever came to the United States, and then tried to figure out how to make a living in this beautiful place, which is, as many of your viewers will know, a rural U.S. state. I don’t regret moving here at all. It’s just stunning.

Paul Nunesdea: It’s so beautiful. Indeed. And, Martin, we normally start our conversations with a question. I’m not sure if Adrian already watched past episodes. Maybe it’s kind of prepared, maybe not, but would you like to fire it?

Martin Duffy: Yeah. Extending from where we just started there, Adrian, we normally invite our guests if there’s something about yourself, any little trade secret, or any little personal secret that might intrigue our listeners.

Adrian Segar: Okay. I’ve been writing a weekly blog for 15 years now. And it’s mostly about meeting design and facilitation, but I write about all kinds of things. My bio is there, so I’m fairly transparent about my life, but there’s something I did when I was living in England—my first career. I have, believe it or not, a Ph.D. in high-energy particle physics. I used to do research in neutrino physics at CERN and was lucky enough to work on an incredible experiment there, maybe one of the most important high-energy physics experiments in the second half of the last century. And there are so many stories. I have one on my blog about being trapped in an elevator with a Nobel Prize physicist. That’s a long story, but it’s on my blog and you can read that!

Adrian Segar: If you had told me at that time that what I would love to do is work with people and facilitate connection between groups of people coming together, I wouldn’t have believed you. I’ve had this long, weird arc of professions, careers, and life experiences that have brought me to this place, which I really love, and I’m very happy. I love doing what I do.

Martin Duffy: Fantastic. Well, that neatly segues us into the theme that we set for today, which is unveiling peer conferences. And the concepts behind peer conferences. Can you elaborate Adrian and we’ll let the conversation take us wherever that conversation might go?

Adrian Segar: I’ll try to make this brief. I’d love to talk in a historical context. When I was an academic —my bio says “recovering academic”— I went to academic conferences as a grad student with all these physicists, and I hated [these conferences] because you’re in a room with a hundred physicists. These are interesting people. The format was some famous physicist that had a lot of status being in the front of the room and giving a speech for an hour. And maybe there’d be five minutes for questions at the end. And the questions were more about showing what a smart person who was asking the question was, than about actually learning.

Adrian Segar: I’m in the audience. I’m thinking, people are sitting here and I don’t know; maybe that’s someone I’d really like to meet, maybe we could work together, maybe we could collaborate, or maybe I have stuff to offer them. And there was no opportunity. We’ve spent all this time and money bringing all these people together and nothing is going on except us listening to lectures. Of course, this was nearly 50 years ago. And the other piece of this strange obsession of mine is that I’ve always liked to facilitate connection between groups of people who have something in common.

Adrian Segar: So, even when I was doing particle physics, I started organizing conferences. When I came to the States and started manufacturing solar hot water systems—this was long before electric solar electricity was viable—I organized probably the earliest solar energy conferences in the United States back in the late seventies and early eighties. But they were all traditional conferences because that’s all I knew.

Adrian Segar: And then in 1992, I wanted to do a conference in a new area: The rise of personal computers, using them in educational administration. And I thought, well, who are the experts, because when you do a traditional conference who do you invite to speak? But there weren’t any experts to invite to speak because it was a whole new field!

Adrian Segar: So it was all new. I thought, how do we do this? And so three of us invited a group together and I invented an approach on the spot. This is in 1992 for a conference. Here we are, we’re all doing the same thing. We mostly don’t know each other. So we have to have some way of finding out about each other, what we do, where we live, anything important, what we’re working on, what our problems are, what cool things we’ve done that other people might want to hear about.

Adrian Segar: So we did that. And it became pretty clear; there’s three or four things here we really need to talk about, and there are a couple of people here who have actually done [each of] these things. So let’s have them [lead sessions]. So we created sessions, we created a conference on the fly. We had no alternative because we didn’t know what else to do. And then at the end of it, we said, well, this has been fantastic. You know, we created this conference, and everyone loved it because it was what the group clearly discovered it wanted to talk about, so what should we do now?

Adrian Segar: That conference has now been going for over 30 years as an annual event. It’s a four-day event, and it’s still designed the same way. It’s a very clearly defined group of people who have something in common, and they go, and you never know what the conference program is going to be.

Adrian Segar: I developed this process. This is how I got into this work. That group spends half a day learning about each other. Who’s there, what they want to talk about, what the resources are, generating a conference program from that. And then the rest of the conference, you run that program. It’s a very informal program. It could be lectures, but that’s rare. It’s usually discussions or small group sessions with a lot of participation. There might be two or three people running a session because it turns out they know something about the topic. It’s very informal.

Adrian Segar: I also, over time, developed processes for figuring out what have we done here. What I call a spective which looks back on what’s just happened, sharing group and personal experiences of what that was like and then a prospective of the future. What should we do now?

Adrian Segar: That group, for example, over 30 years has come up with several initiatives outside the conference. “We need to do this, let’s set up a task group,” et cetera, and has created whole new projects as a result. But the conference itself is different every year. It adapts to what the people who come to it want and need, and they love it!

Martin Duffy: So who drives it? What’s the underlying driver? Are there multiple different groups with different agendas or different topics of interest? How does that work?

Adrian Segar: So, again, maybe the historical perspective is a good way to go. I loved doing this event. People loved it. It was clearly going to continue. Other people found out about these formats and asked me to do these conferences on topics that I knew nothing about.

Adrian Segar: So I thought, well, this is great, but will it work if a group of people who own garden centers get together and want to talk about stuff? Or people who own sports venues in the United States.

Adrian Segar: I eventually discovered over the next 10 years that it seemed to work for everybody. Everybody loved this format that I’ve just outlined to you. And that’s when I decided I would write my first book, Conferences That Work, Creating Events that People Love, to talk about the format, and make it available to anyone who wanted to use it. That book came out in 2009, and suddenly I was in the meeting industry. This was my fifth career. Though I’d been convening events for much longer than that; well over 40 years.

Adrian Segar: So the answer to your question is, I wrote a book, and then, with a website and a blog, people started finding me and asking me to [design and facilitate] events. Once I started doing this in the meeting industry, I was doing a huge number of events. Over time, I experimented, tried new things and new approaches, and eventually wrote a couple more books on different aspects of how to do this work.

Martin Duffy: Super! So is there a framework or a process that you adopt generically that you can tailor per the different particular groups that you end up working with? Is that how it operates?

Adrian Segar: Yes, there’s so much detail! What I like to do to describe the general process is something called the conference arc.

Adrian Segar: You’re creating an event that becomes the best possible event for each person who comes. That’s my goal. That [simple goal] implies so many things.

Adrian Segar: It implies that you can’t have a predetermined agenda because you don’t know what the people at your event are actually going to want to do. You don’t know what resources they have that might be amazing for other people who are there and so on. So the framework is very simple. I think of these events as having three pieces. A beginning, a middle, and an end!

Adrian Segar: At the beginning, I use a number of processes where we learn about each other. The core one, which I use a lot, is called The Three Questions where everybody at the event—and you divide into smaller groups if it’s a really large event to do this—answers three questions to everybody in their group. Maybe as many as 40 or 50 people in each opening session.

Adrian Segar: There are no wrong answers to these questions. You can’t answer these questions incorrectly. There’s a fixed amount of time for each person. So we level status differences. It doesn’t matter whether it’s the head of a 50,000-person association or someone who just started working there last week, they get the same amount of time.

Adrian Segar: And the three questions are:

1) “How did I get here?” Which might be answered, “I drove down the street”, or “I’ve been coming to this conference for years and I love it” or whatever it is.

2) “What do I want to have happen?” In other words, if this conference was amazing for me, what would I want it to look like? What would I want to be talking about? What problems do I have that I’d love to find someone to help me work on together? What things do I want to do and I want to find other people who want to do them?

Adrian Segar: And the third question is:

3) “What experiences or expertise do I have that others here might find useful?” There you get to say perhaps “I did this cool thing last year”. And at almost every event where someone says something like that, there are maybe 20 people in the room who are “Oh, we’re just about to do that! Can you talk about it?” and bingo, you have a session that no one even knew was needed.

Adrian Segar: That’s the beginning of a peer conference. The middle is the conference’s bread and butter. You run those sessions. I have a whole set of fairly simple instructions for people who haven’t been to these conferences before so that they get the best out of those sessions. They’re very participatory. I have a double-sided piece of paper with tips for anyone who’s facilitating or leading those sessions, and I find that most people with these instructions can do very well.

Adrian Segar: And then the third part, the end of the Conference Arc, is typically two sessions. [The first is] a personal introspective, a time for people to think in the moment: what has happened for me, what do I want to change in my (usually) professional life as a result of being here? [We do this] while the experiences are fresh. Because how often do we go to a conference and go away with our heads full of ideas and then you’ve got to go back to work and you’ve got a million things to do? And those notes you wrote and those ideas never come to anything.

Adrian Segar: So the personal introspective is an opportunity to [evaluate your conference experience] and make it more likely that the changes you experience at the conference that you decide to make for yourself will actually happen.

Adrian Segar: The end of the arc is the spective. I just wrote a blog post about the spective, which is where the entire group talks individually about their experience of the conference. They start with the stuff that they like, and then they continue with stuff—not that they didn’t like, but—they think can be improved or changed in some way. Two separate pieces.

Adrian Segar: The spective does two things. It gives the whole group a collective experience of what the event was like, We all have our own experience, and you might say, I really didn’t like that session. And then you hear three other people say “That session was fantastic for me”. And that doesn’t change it for you, but it gives you a feeling of why the whole community did that.

Adrian Segar: The second thing is that the spective creates tremendous community bonding. You’re saying, we just had this experience together. And out of that often comes things that the group wants to do in the future. For example, at a first-time conference, people might say, “We have to do this again! Let’s meet next year”

Adrian Segar: So that’s the big picture. And then there’s tons of stuff that I’ve developed to deal with special cases—there are all kinds of processes. Those are in my second book, which is like a tool kit for process design for participant-driven and participation-rich meetings.

Martin Duffy: Let me step back a little bit. Adrian, you said something about halfway through your comments. You said: “There is no agenda”. So the conference starts off with no agenda. So if there’s no preordained agenda, what’s the hook? What’s the reason that people show up in the first place?

Adrian Segar: Why are they coming? There’s a Japanese word Ikigai that means my reason for getting out of bed in the morning. My Ikigai is facilitating connection between groups of people who have something in common, which is basically every association that exists on this planet. And things that we don’t even call associations because associations are actually incarnations of what one would generally call communities of practice.

Adrian Segar: You have groups of people who have something in common. Every single association started with a group of people who said, we’re all cardiac surgeons, or we’re all folks concerned about climate change or whatever it is, and we want to meet and talk about that, and then the group gets formalized.

Adrian Segar: So, the reality is there are hundreds of thousands of these groups all over the world. In the United States, there are I don’t know, probably over a million associations alone. And there are plenty in Europe. They tend to be larger in Europe and less of them because a lot of the things that people build associations for in the United States are handled at a governmental level in Europe and in other countries.

Adrian Segar: So the answer to your question is, you define a community. There’s a community of practice. There are always some vague edges. But you have a group of people…for example, I did a conference for anyone who owned an independent garden center in the United States. All those people know each other.

Adrian Segar: And there’s an association for them, so they have a lot in common to talk about, and so do cardiac surgeons. That’s how you define a group. [Ultimately,] the group is self-defined. Then when you frame the invitation to the conference, you have to make it clear who you’re inviting.

Adrian Segar: Maybe it’s a certain kind of cardiac surgeon or people who own independent garden centers rather than large chains, for example. So it’s clear when the invites go out. “I’m in that group. This is interesting. I will be meeting with other thoracic cardiac surgeons” or, whoever the group is that’s of interest to me.

Adrian Segar: You tell them that it’s a format where they will actually get to ask questions and get problems solved that they personally have, that the conference is designed to work that way, and the conference may well tap their valuable knowledge and experience and expertise that they don’t even necessarily know is valuable until 20 other people say, “Wow, that’s really a cool thing you’ve done. We want to hear about it. We want to learn from you.” All those things become possible.

Martin Duffy: So we haven’t set an agenda, but we’ve set a thematic area. We’ve identified a target audience. We’ve pushed out the invites, we’ve set the date, we’ve got the venue, people turn up, and now what happens, and let me be a bit more specific. So very often there’s going to be somebody who’s going to cheerlead from their perspective and they’re not always necessarily the best people to hold a group together. But they’ll almost always want to take the lead. Is that what happens or is it more structured and more managed?

Adrian Segar: The subtlety of designing meetings is that you need people who I would call facilitators. I define myself as a meeting designer and facilitator. So clients will often ask me to facilitate.

Adrian Segar: The meeting is usually about something I know nothing about. I’m very curious and I’m always interested and I learn a lot. [But there are different approaches.] For example, Eric de Groot, who you mentioned earlier, he’ll do corporate events. You’ve got situations where two companies are merging or something like that. How do we make that happen successfully and so forth. And he’s brilliant at that. My focus is much more on [creating a] good experience for each person who’s there.

Paul Nunesdea: It’s interesting. It’s fascinating. The world of meetings is fascinating because now we see a kind of specialization. Eric is more focused on corporate meetings, and Adrian is more on association meetings.

Martin Duffy: What Adrian said: his focus is on personal experience, as opposed to, let’s say, corporate experience. You know, that’s an area that I’m kind of intrigued to understand in a little bit more detail as well.

Paul Nunesdea: Absolutely. Absolutely. But what crossed my mind, Martin, is that in the world of corporate meetings, every one of us is also likely a professional from an association. So, if we are not in a corporate meeting, we will probably end up in an association meeting.

[Short tech change break]

Paul Nunesdea: Thank you so much for watching us. Dear viewers, we are on episode three of Talk to Your Doctors. This is a LinkedIn live event series. Co-hosted by me and my dear colleague, Martin Duffy. Today, we have a special guest, Adrian Segar from the United States, and we are having a wonderful conversation. Martin, can you just bring us back to the thread?

Martin Duffy: I’ll do a really quick synopsis. Adrian, you started off by telling us about how your first career in particle physics brought you along to academic conferences, which you found a little bit stifling of participation. You found a way for new people to come together in groups to engage hearts and minds in a way that was based on a design with a beginning, middle, and end to the conference.

Martin Duffy: Your beginning has three key questions that enable people to engage and interact with each other at the interpersonal level. And out of that flow the common interests that they have in whatever the thematic area of the conference is. The middle part of your session is then to run the discussion using facilitators within the groups themselves, and you’ve got guidelines and so on for that.

Martin Duffy: And then at the end of the conference, you said to us that there are two different endings that you try to focus on. One is the personal kind of introspective. What did people introspectively take or get from the conference? They do that at the very end rather than three days later when a lot of it might have gone out of their minds.

Martin Duffy: And the second [ending] is to look at the collective perspective, so it’s a kind of feedback within the group about the conference itself. What was good and what we might improve the next time. Interestingly then, you took us to framing the invitation to the event, which now takes us into particular groups with particular individuals in the group, where there’s a thematic area.

Martin Duffy: And then your focus is typically on the personal experience that people get from the conference that they’re attending. And that’s where unfortunately the technology let us down. We had to pause and we’re back. So looking at it from the personal experience point of view, as opposed to your colleague Eric de Groot, where you suggested Eric will be more focused on the corporate perspective, while your perspective is at the personal experience level. Could you expand that idea just a little bit for us, Adrian, to give us a flavor of what you’re doing?

Adrian Segar: Yes, it goes back to my joy in bringing people together to connect at an individual level in ways that work for them.

Adrian Segar: I give them the support and structure for them to create, the connections and the sessions that they need and give them good process to allow them to run those. I [should] add in the beginning piece, after the uncovering of who’s there, what they want to talk about. and what the resources are in the room (remember the saying “the smartest person in the room is the room”).

Adrian Segar: There’s an art in doing this. I use all kinds of techniques, to create an event that’s maximal for the participants. Eric will get a client who says, this is what we want to achieve for this organization or association. He will come up with some very creative ways, [e.g.] using elementary meeting techniques, which are really great.

Adrian Segar: He’s coming up with ways to create a meeting that serves the needs primarily of people at a higher level in a way that works for the whole organization. Whereas my focus is from underneath. My focus is I’m interested in every single person who comes.

Adrian Segar: How can I make their experience maximally useful for them? And what I’ve found for decades is that when you do that, the event also benefits the stakeholders, the sponsors, the folks who brought the event together. The leaders of the association are happy because the event is very energetic. Participants are very happy. The closing session often comes up with whole new directions for the group to go that are often bottom-up. They’re not imposed by leadership at the top, but by people in the group, the people who form it. That community of practice is saying, “Hey, this is what we want to explore. This is where we want to go.”

Adrian Segar: And the resulting initiatives are very likely to be successful, much more successful in general than top-down directives of [leadership] saying, “We think we should go here”. Their intentions may be great. But in fact, as we all know, [top-down] initiatives don’t always pan out.

Martin Duffy: So what kind of timescale for this type of conference?

Adrian Segar: That is a wonderful question. And again, that’s part of the art of designing a meeting. For example, that [original] conference has been going on for 32 years. It’s a four-day conference. So you have plenty of time to do all kinds of stuff. It starts up with a half day and then there are three full days. But sometimes people don’t have that much time, that’s actually a rarity these days. I can do something useful in any amount of time. For example, the probably most well-known format in this genre is Open Space, Open Space Technology. You can run an Open Space event in two hours. And I’ve written some critiques of Open Space and some people think that what I do: “Oh, it’s got to be Open Space!”

Adrian Segar: Open Space is only one of many formats. It has one advantage in that it’s fairly well known. It has some disadvantages too, in that it tends to, in my experience, cater to extroverts who are happy to come up at the start of the event and say, “I’m going to do a session on this in room so and so”. And it’s true that people don’t have to go to [that session], but there’s some time wasted there; it’s inefficient because you go and, “This isn’t really what I wanted”.

Adrian Segar: I believe if you’ve got the time, if you have half a day, or a day or a day and a half, or two days, it’s worth doing what I described to you in general terms at the beginning of the conference. Where you take some time to hear from everybody, not just the people who say “I want to do a session on this”. There’s nothing wrong with that, but the introvert who actually is a fount of knowledge on a topic isn’t likely to stick their hand up and say, I want to run a session. You don’t hear from those people. I’ve talked to people who have said “I know there was a world expert on this topic in the room, and they never offered a session because that’s the kind of person they are.” That person would be far more likely via the processes that I use to be seen and acknowledged, and people would say, “We really want to hear from you, on X that you know a lot about.”

Martin Duffy: And that person is much more to talk in the event. Yeah, I was going to specifically ask you about Open Space because I’ve run a number of Open Space events myself. Some of the things you were describing are very similar to Open Space, but actually, some of the things you’re describing are quite different from Open Space.

Martin Duffy: So how would you characterize Open Space? As a variation of peer conferences, or would you describe it more as a separate type of format on its own?

Adrian Segar: No, it’s definitely a participant-driven participation-rich format. And that’s how I describe the peer conferences that I run.

Adrian Segar: I’ve run Open Space when time is really limited. If you’ve got two hours and you’ve got a group together, Open Space is probably about the only reasonable format you can use. But I believe from my long experience, if you have more time, it’s well worth spending some time learning about the folks in the room.

Adrian Segar: The amount of time it takes? You don’t have to take half a day. Half a day is plenty of time for everybody in a group to get a really good picture of who’s there and the resources in the room, but you can do that in a much shorter period of time at a shorter event.

Adrian Segar: So part of the art of doing this is, clients say, “I have a day and a half. What should I do with it?” And I can say. “We should spend this much time on this, this much time on that, this much time on this.” For example, maybe there’s not enough time for a personal introspective because it’s a short event.

Adrian Segar: We’ll just have a spective at the end. That’s the benefit of using an experienced meeting designer because I’ve done so many of these and know how to best use the available time. And there are certain situations where you do something different [because your client has a specific need]. For example, I did a conference in Philadelphia last summer where the U.S. association client was designing the 50-year anniversary of the association, and they wanted to talk about the future. It was the first time they’d ever had a conference, and when they brought me in they had already invited an expert on forecasting the future. And then they scheduled a panel with their experts and that person.

Adrian Segar: They bought me in at that point to open up the event and say, “Well, what do we want to talk about? Having heard all these really good ideas and thoughts about the future? What do people now actually want to talk about?” I used a very different technique from The Three Questions at that point, because a lot of information had already been uncovered.

Adrian Segar: The other thing I’ll mention that I really love to do and specialize in is taking a large group of people with a significant problem that’s group-wide and facilitating a large group discussion on solutions to that problem.

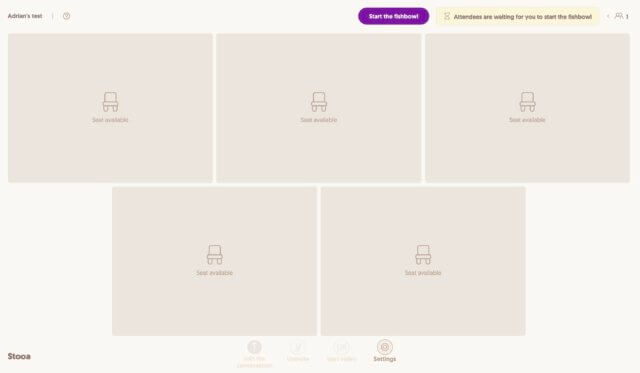

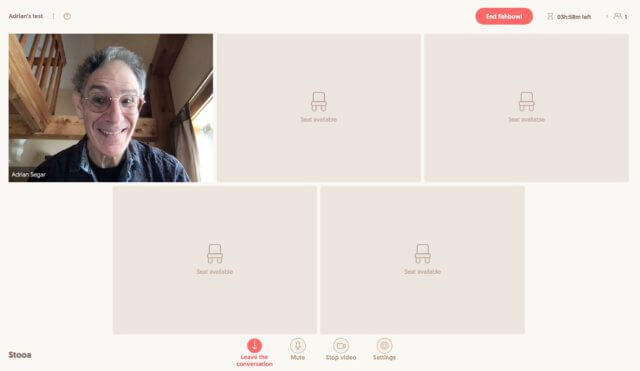

Adrian Segar: I have a technique called the fishbowl sandwich which I developed out of need. It works incredibly well. It taps the wisdom of the group for ideas. It uncovers people who don’t even know they have a fantastic solution that many people in the room love, want, and need.

Adrian Segar: I’ve experienced this numerous times. Someone comes up on stage and says, “Well, I don’t really have this problem because I do X” and half the room goes, “Oh, that’s brilliant!” And the association magazine editor comes up and says, can I interview you about that. It’s just incredible. The person was just someone sitting in the audience thinking, well, I don’t have this problem. And the process brings them out on stage. And they share and it transforms the group and you find three other people who have fantastic ideas. It’s a very effective session for dealing with large group problems.

Martin Duffy: When you say large group, Adrian, what scale are we talking about?

Adrian Segar: Good question! You can do what I just described with hundreds of people. There’s an issue about how some of the things I do scale, because, as you know, a meeting with 50 people when facilitated right is very different from [what you can do] in the same amount of time [facilitating] a thousand.

Adrian Segar: You have to do different things. Typically though, the best events are relatively small, up to a hundred people, because there’s no way you can facilitate really effective connection between, say, 500 people in a day. I can do that better than a traditional conference can, but you’re not going to meet all the other 499 people and get to know them in a day. It’s impossible. Human beings don’t work that way.

Martin Duffy: Yeah. Really interesting. The fishbowl sandwich, just the name is intriguing. What is, or is there a trade secret behind that?

Adrian Segar: No! I write about these things! One of my mentors, Jerry Weinberg, a long time ago said “Give away your best ideas”, don’t have any secrets, share. With my clients, I find this works very well. [They appreciate learning how to solve their problems themselves.]

Adrian Segar: So the fishbowl sandwich, it’s described in my second book in detail. It’s a very simple technique. It starts off with a pair share in the audience. When I use it for problem-solving in large groups what you do is this. You state the problem. You might have three people who have some ideas on how to solve the problem come up before the group and give an—absolute max 5-minute—description of how they are approaching this problem.

Adrian Segar: So that primes the audience to think about the problem in a creative way. Then you do a pair share. You get everyone in the audience in pairs and each person talks [with their partner] about their personal experience of that problem. How they’re dealing with it, if they have some way of dealing with it. Then they switch. So that’s a standard pair share. This gets everyone in the room to say something to someone else in the room and that opens up the session.

Adrian Segar: And if someone says, “I did this” and the other person says, “Wow, that’s really cool. Maybe you should say something in the main part of the session because I think other people would be interested.” So you’ve primed everyone.

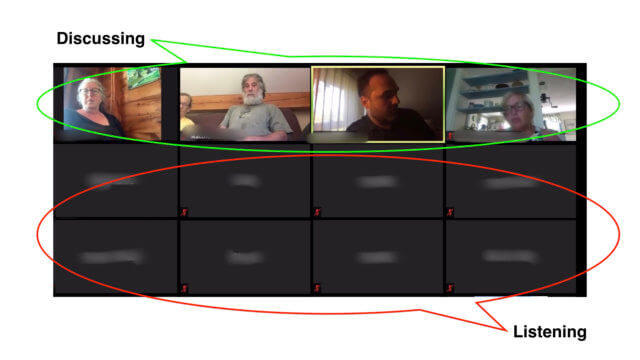

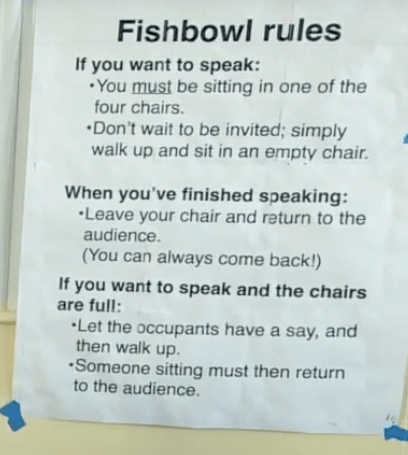

Adrian Segar: Then I run a fishbowl. You know what a fishbowl is—well, there are several kinds—but I have a stage, at the front of the room. I’m in a chair, there are perhaps four other chairs, and the fishbowl, for those of you who don’t know what that is, is a wonderful technique for working with large groups of people and controlling conversations.

Adrian Segar: The rules are very simple. You can only speak if you’re sitting in one of the chairs in the front. And you invite people up to speak. So you say, “Okay, we’ve heard some things. You’ve had some discussions. I’d like to hear people who have, who want to talk about their particular problem, or maybe you’ve got a great way of solving it”.

Adrian Segar: “If you want to say something, come and sit in a chair.” People sit in the chairs. I have the mic, maybe a few mics. I facilitate a conversation between those people. Another rule of fishbowl is when you finish what you have to say, you leave your chair. And another rule is if all the chairs are full and people are sitting up there and someone else comes up then someone in one of the chairs has to leave.

Adrian Segar: So, you have a conversation facilitator and a maximum of four other people at any one time. Sometimes two people are talking with each other, sometimes individual statements, and so on. And it’s very dynamic.

Adrian Segar: Then the last part of the sandwich. It’s called a fishbowl sandwich because it’s a fishbowl sandwiched between a pair share at the beginning and a pair share at the end. The final pair share is “lessons learned”. What did I learn today? You do that with someone else in the audience and you say, “Wow, that idea was really a great idea. I’m going to do that with my business group when I get home” and so on. That’s a cementing technique like the personal introspective. Pair shares are very good at reinforcing [potential] change.

Adrian Segar: The other fundamental thing about the conferences I do is that I’m always interested in creating change in people’s lives. If you go to a conference and you have a good time, but nothing ever changes, there isn’t any point in going apart from having a nice time. I want to learn stuff. I want to get new ideas. I want to maybe change my life. I find someone who can offer me a new job or a new position or a new way of thinking about a problem.

Martin Duffy: The really interesting thing that I’m picking up thematically, that I’m picking up from each of the points that you’re elaborating for us is this idea of personal experience. So, you know, the idea of using the pair share, pairing discussion, where that’s opening up, creating the kind of the unbounded part of the conversation. But even still, with the fishbowl part, we still have four people having a conversation at an intimate level. And then the pair share at the end is consolidating the takeaways, and it’s people personalizing.

Martin Duffy: So that seems to be a fundamental theme that I can feel threading through everything that you’re describing there, which is really fantastic.

Martin Duffy: In terms of scale. You know, where you run an event that, say, between 50 and 100 people, can you give us a sense of how you manage to bring that personal into that scale of collective? How does that mechanically work in your events?

Adrian Segar: Well, the whole event design is designed to model and support. personal interaction, fruitful interaction, not pointless stuff like icebreakers which I think are terrible. You know, a lot of people think, “Oh, we’re going to do that.”

Adrian Segar: No, the crucial thing is—and that’s why the three questions that I’ve talked about are so important—to get to the heart of what it is people want to know about each other at the event. When I was that grad student sitting in an academic conference, I wanted to know about that person three chairs away from me. I wanted to know what they did, and why they were at this conference. I wanted to know what they were working on. I wanted to know what they knew about. That’s all the information you need to have a conversation. So when you design these formats, the wonderful thing I’ve learned, because I’ve done a huge amount of group work, is that you can gently and hopefully ethically take people to places they would never go by themselves.

Adrian Segar: We [facilitators] all know this. That’s one of the things I love about group work. I love taking people into these processes, and they suddenly discover that they’re talking with their peers in a way that they love. “Wow, I went to the session. I saw that there are three people here I really want to talk to, and then I can get to go and talk to them.” Maybe in a session, maybe out in the hallway. “And I found that out on the first half-day or the first few hours of the event. And even if nothing else happens at the event, the fact that that session introduced me to those people is incalculable.” Maybe it changed my life or their life.

Adrian Segar: So you build support for all these interpersonal stuff. And the norm that it’s okay to communicate and talk to you gives them a framework to do it in a way that’s not threatening. Then you sit back and let them do it. You watch it and you make sure it’s going according to plan, but they do all the work.

Adrian Segar: That’s what facilitation really for me is about; if your design is good you don’t need to intervene much.

Martin Duffy: And I think when you bracket it at the back end…very early in our conversation you mentioned the idea of closing out and you have the two steps to closing out, which is the personal introspective. And then there’s the [spective] piece.

Adrian Segar: Yeah. The spective is a combination of a retrospective, looking back, and a prospective, which is looking forward, and I call [the format] a spective because it’s both.

Martin Duffy: Okay. So the future looking spective that you offer, how does that work in practice? What’s what does that sound like or feel like in the group?

Adrian Segar: [For] the process I usually use for that, I start with a pair share or trio share. To get people thinking what they might say, they talk to each other and say, yeah, this is what I really liked.

Adrian Segar: So everybody in the room is already thinking about what they liked. And then I use a very simple technique called plus delta, which works really well. You do it with a flip chart or you can do it with a Google doc. I have two mics, a plus mic and a delta mic, and I have people come up and I say, “Okay if there’s something you liked about this event that you want to share, come up to the plus mic. Form a line, be brief, tell us this is what I liked: a session, the food, meeting this person, whatever it is.” You get a stream of [positive feedback]. And I keep inviting the audience up. You can do this with hundreds of people. And in half an hour, sometimes less, you can get very good information about what was great about the event.

Adrian Segar: Sometimes I have clients video the respective because what people can turn into amazing testimonials. So there’s the plus mic and then eventually the pluses peter out and then I open up the delta mic and I explain “This is not about ‘bad’ stuff!”. This is about what would you change to make this event even better. And people come up. “I think we should do more of this”, “that session could be improved by…”, etc. I have two mics because someone may come up to the delta mic and say, “I think we shouldn’t do X anymore”. And then someone else in the audience will come up to the plus mic and say, “Actually, I thought that was really good.”

That’s plus delta. It’s a very good technique. I usually have the client recording what people say, because that’s incredibly valuable to the stakeholders [as feedback] for improving the event for next time.

Adrian Segar: And sometimes the plus delta includes a piece that’s client-specific. Occasionally, clients will ask me to address an issue that has been troubling the association or one that comes up during the plus delta. It’s often pretty obvious. So after the plus delta, I may facilitate a discussion, which might be a fishbowl sandwich on a specific issue. Or we might hear an overwhelming desire during the plus delta, and I’ll feel compelled to say, “Okay, folks I think we should spend a few minutes figuring this out because it’s very clear that this group wants to do X. Let’s have a discussion on how that’s going to happen right now while it’s really fresh.” For the group spective, that last session, I usually budget it for maybe an hour. And it’s often less than that, but that hour allows us time in case some issue comes up that needs individual attention.

Martin Duffy: Yeah, I’ve used a technique called, I call it PMI: plus minus interesting. It was developed by Edward De Bono. Very similar principles. It’s a plus and a minus and whatever people found interesting. But it’s the same concept of delta, where we find the difference in perspectives. And then we can actually lever off that to say, well, where, where would you take this conference next or the next conference? Where would you take it differently? Which is really cool.

Martin Duffy: Paul, I’m watching the time, are we at our limit at this point?

Paul Nunesdea: We are at our limit, but still, I have one last question to ask Adrian, if I may, Martin, and then over to you to the wrap-up because it’s a privilege to have Adrian Segar here.

Paul Nunesdea: The mind beyond the peer conference model, it’s even more than a method model to design and create your own conference. Adrian, I’ve learned so much from the few comparisons you made with Open Space Technology. It’s really interesting because it never struck me how important it is for a group to meld before they actually [start to work together]. Precisely what you accomplish is that melding at the start that [allows] people to join a safety zone where they then will be able to learn from each other. That’s amazing.

Paul Nunesdea: A question to you. You rightly said that you’re positioning yourself in the meeting industry [where] there’s still these traditional conferences that attract people by the thousands and are extremely expensive. I normally compare them to people in a library buying a book, right? Because this is content that you want to acquire when you buy those books; you can go to that conference, and you pay for a ticket for content, right?

Paul Nunesdea: But in the end, it’s always back to the principle of you leaving that conference maybe with some wonderful experience, but with little change on yourself. So how do you convince meeting owners, the people who organize these large events that a peer conference model is more sustainable, more effective? How do you convince them?

Adrian Segar: Well, there’s no one answer. My rule of thumb, and I think Eric’s too; my rule of thumb is if I can actually get to the decision maker at the organization for ten minutes, the CEO, I can convince pretty much anyone. And the tragedy is that very often middle management or upper management contact me and say “Hey, I love what I read about your stuff” or “I heard about it.” Or “a colleague of mine experienced it and we want to do this.” And then it’s not unusual for the CEO to be inaccessible. I say, “Well, can I talk to your decision-maker? Because I can convince most people if I talk to them directly.”

Adrian Segar: And sometimes that’s impossible. Sometimes at these larger organizations, this person, you can never speak to them. And I have to say that when I don’t, it’s rare for my approach to be adopted. So many associations are still stuck in these hierarchical cultures that don’t really reflect an effective environment for creating change and, fulfilling the needs for which the organization is created. We still have a lot of top-down culture. So the answer to your question is, I get frustrated with it too! It’s not [as simple as] a client approaches me and then hires me, As a consultant you need to be prepared for people to reject your advice. You have only influence, no authority.

Adrian Segar: The plus side of this is that I love the clients that I get to work with because they get or at least partially get enough to trust what I do to actually experience it. And when they do typically they will adopt how I have designed their meetings. I influence them, and their future meetings, even if they don’t use me again, are different.

Adrian Segar: So, I love running in-person meetings. I [design and facilitate them] online as well. and spent a lot of time, since COVID, figuring out how to create online what I do in person.

Adrian Segar: But, it’s a perpetual struggle to change [traditional meeting formats]. And I’ve written extensively about this in my books and on my blog. Why? I think Eric talked about it too. We’re all indoctrinated in school to sit there. It’s the model every single one of us still gets. There’s a person in [the classroom] who talks to you for fifteen years who knows more than you do. And that is how you get taught. That’s how I was taught for years. When I was a college teacher, I taught the same way too. I didn’t know any better.

Adrian Segar: [I have a] vocation and desire to spread the way I describe to create meetings. Participants’ most common response is, “I don’t want to go to traditional meetings anymore”. And that’s growing, and we do see that, luckily, in the meeting industry, and now people in meeting magazines talk about creating connections at conferences, not just content, and how we create connections. [Many] still don’t know how to do it, but at least we’re moving in the right direction.

Paul Nunesdea: And for you, dear viewers watching us, if you want to plan a meeting, please contact Adrian Segar. There’s a wealth of [free] resources on his website, conferencesthatwork.com.

Paul Nunesdea: Myself, I also use Adrian’s stuff when I prepare some of my meetings. And it’s definitely well worth it to read and access those materials. Martin, this reminds me that the more association meetings we have that are peer-based peer-model conferences, maybe that’s the kind of energy that you get in association meetings. Once you get back in your corporate environment in your organization, then you say, “Oh my God, this meeting sucks.” Right? And I think this is probably going to force corporate meetings to be more effective as well. Martin, I think we are close to the time for the wrap-up.

Martin Duffy: Yeah, I did a small summary because of our technical glitch in the middle there.

Martin Duffy: But actually, just in the last 15 minutes, Adrian, there’s one really significant takeaway that I’m getting from what you’ve said. It was a throwaway comment you made, but you talked about bottom-up versus top-down. And when we compare and contrast what Eric talked to us about on our last episode, that would be more reflective of a top-down corporate-type approach which is fine.

Martin Duffy: No judgment made on that. But, how you describe your approach is very much bottom-up. From my own experience, what I might suggest is that the fear of the peer conference approach might just be a fear that the bottom-up is going to send us in a different direction from where the top-down thinks we should be going. Are we afraid that we won’t be able to handle the shift required? Or, do we embrace the possibility that by adopting a bottom-up shift, we can all actually head in a much more unified, harmonious, and productive direction?

Martin Duffy: So I think that’s fascinating. The concept of peer conference, as you’ve so generously shared with us, Adrian, I think it really does open the possibility of that bottom-up input to the overall future direction that our group or our collective or our association, or our organizations, whatever they make; that that bottom-up input, there’s a ready-made way in which we can get that.

Martin Duffy: The question is, Are we brave enough to try?

Adrian Segar: I think that’s an excellent point. And, I agree that a lot of the difficulty in introducing these kinds of meetings to replace or improve on existing meetings is the fear of something unknown, of something one doesn’t have control over. In a hierarchical organization, people like to know we’re going [somewhere specific]. [It’s comfortable that] people are leading us and so forth.

Adrian Segar: What actually happens—and I don’t think this has ever not happened—is that the folks at the top discover that these events are incredibly useful for everybody, including them and the participants. And the folks who are not at the top really appreciate the leadership for giving them these opportunities and are grateful.

Adrian Segar: In my experience, this creates a stronger organization. So it’s a win-win for everybody. The leaders get really good feedback from these events, and also really appreciate them. And the people in the organization or association are grateful to them. It’s like, “Thank you, thank you, thank you for making this event much better than the traditional event we used to have or I’ve gone to online”.

Adrian Segar: So there is no downside. But you’re right. There’s fear. Change is scary. I’ve written a lot on my blog about facilitating change, the difficulties of doing that, how to facilitate change, and leadership models. There are all kinds of resources there!

Adrian Segar: So it’s a pretty popular website. I would like to mention that [conferencesthatwork.com] is the most popular website about meeting design in the world. And there are over 800 blog posts there. It’s a great resource, that includes free chapters from my three books.

Paul Nunesdea: We are on a mission here, Adrian, and thanks for joining our list of guests here and talking to Your Meeting Doctors. We’re on a mission here to convert the meetings of the world to meet in better ways.

Adrian Segar: I agree with you. I’m with you. 100%. Thank you very much for inviting me here today! I love talking about this and I appreciate you. And it’s great to meet you and find some more allies in this journey.

Martin Duffy: A real pleasure meeting you, Adrian. Thank you very much indeed for your time. Bye now.

Adrian Segar: Okay. Take care everyone.

Martin Duffy: Bye. Bye. Hey, what a fantastic conversation with Adrian!

Martin Duffy: And on his final point, Paul. He raised an interesting challenge and a challenge that Eric de Groot raised with us actually in our first episode. And that’s the challenge of convincing the powers that be within organizations that there may be a different way and a better way to manage their resource of meetings in totality.

Martin Duffy: So not just the special meetings or the special conferences, but equally their day-to-day meetings. So perhaps we could line something up for a future episode on that.

Tired of meetings that don’t end on time? Who isn’t? Things were bad enough when we held our meetings in person. Now so many meetings are online, it’s easy to saddle remote workers with back-to-back meetings. When one overruns, you’re late to the next one. Hey presto, your tardiness snowballs! (And, no,

Tired of meetings that don’t end on time? Who isn’t? Things were bad enough when we held our meetings in person. Now so many meetings are online, it’s easy to saddle remote workers with back-to-back meetings. When one overruns, you’re late to the next one. Hey presto, your tardiness snowballs! (And, no,  I’m a big proponent of

I’m a big proponent of

What’s the best way to facilitate a community discussion? Recently, I had to answer that question at short notice. My task: design and facilitate a two-hour community discussion in response to a bombshell announcement made by the largest employer in my tiny rural hometown of Marlboro, Vermont.

What’s the best way to facilitate a community discussion? Recently, I had to answer that question at short notice. My task: design and facilitate a two-hour community discussion in response to a bombshell announcement made by the largest employer in my tiny rural hometown of Marlboro, Vermont.

How often have you heard “Any questions?” at the end of a conference session?

How often have you heard “Any questions?” at the end of a conference session? In less than three minutes, you can use pair share to improve conference sessions. The technique is simple: after pairing up participants and providing a short period for individual thinking about an appropriate topic, each pair member takes a minute in turn to share their thoughts with their partner. (More details can be found in Chapter 38 of

In less than three minutes, you can use pair share to improve conference sessions. The technique is simple: after pairing up participants and providing a short period for individual thinking about an appropriate topic, each pair member takes a minute in turn to share their thoughts with their partner. (More details can be found in Chapter 38 of