The Right Place: Three Encounters with Strangers in Crisis

Read the rest of this entry »

Read the rest of this entry »

Professional, cultural, and social online communities are at risk. Xitter is in the final stages of enshittification. Facebook is inundated with advertisements and extensive data mining practices. LinkedIn groups’ algorithms bury most comments and reduce the visibility of posts with links. While private groups on major platforms remain functional, opaque and ever-changing algorithms control what users see, and the future viability of these groups is uncertain.

In addition, all corporate platforms are vulnerable to changes imposed by the owners, who can sell them at any time to new proprietors with different visions for operation or monetization, potentially further compromising the user experience.

Read the rest of this entry »

In 1997, Dar Williams, inspired by listening late at night to New Hampshire and Vermont’s progressive radio station WRSI The River, wrote the song “Are You Out There”. Her beautiful song about audiences and humans’ desire for connection speaks to today’s events industry.

Why? First, listen!

[Verse 1]

“…You always play the madmen poets

Vinyl vision grungy bands

You never know who’s still awake

You never know who understands and

[Chorus]

Are you out there, can you hear this?

Jimmy Olson, Johnny Memphis

I was out here listening all the time

And though the static walls surround me

You were out there and you found me

I was out here listening all the time

[Verse 2]

Last night we drank in parking lots

And why do we drink? I guess we do it ’cause

And when I turned your station on

You sounded more familiar than that party was…

[Verse 3]

…So tonight I turned your station on

Just so I’d be understood

Instead another voice said

I was just too late and just no good

[Chorus]

Calling Olson, calling Memphis

I am calling, can you hear this?

I was out here listening all the time

And I will write this down and then

I will not be alone again, yeah

I was out here listening

Oh yeah, I was out here listening

Oh yeah, I am out here listening all the time”

—Lyrics [full lyrics here] courtesy of Genius

Like Dar Williams, a true fan of obscure (at the time) music, people search for experiences that meet their wants and needs. We yearn for connection and look for opportunities to get it. Events are the most powerful opportunities for connection (and learning). While today’s radio is, with few exceptions, a pure broadcast medium, it’s available to anyone with a radio who wants to turn it on and find an interesting program.

Event professionals must remember that their events’ true fans are “out here”. They are the people who will form the nucleus of your events’ success. These days, we have far more powerful tools than broadcast radio to find true fans. Use them!

The young Dar Williams learned through her radio that other people like her “got” the music she loved.

While listening late at night, she realized that she was not alone.

Well-designed events transform audiences into a community.

Community meets a fundamental human need, for connection and belonging. Well-designed events create authentic community through interpersonal experiences at the event rather than attempting to manufacture it through entertainment and novel environments. Such events allow attendees to be truly heard and seen.

Tap into the power your events possess to create genuine community. Participants will become faithful attendees because they will not be alone again.

During a 1992 conference, I created the first of what I now call spectives. A spective is a plenary closing session that combines a retrospective (looking back at what just happened) with a prospective (looking forward into the future).

My visual metaphor for a spective is the two-faced Roman god Janus, who was “the god of beginnings, gates, transitions, time, duality, doorways, passages, frames, and endings”. [Fun fact: The month of January is named for Janus.]

I won’t repeat the details of leading a spective here because they are covered comprehensively in all my books. (You can also learn a fair amount about spectives by searching the posts on this site.)

You’d think spectives would take more time the larger the group, but they scale surprisingly well. Most spectives don’t include facilitated discussion of uncovered themes and issues and typically take from fifteen to forty-five minutes. [TIP: I usually schedule an hour. This means the event usually ends early, which participants appreciate 😀.]

They are a perfect way to end a conference because:

I’ve found that spectives are a fantastic tool for participants to get a big picture of what an event has been like for the group. This informs their own experience. A participant may learn that others shared their specific experience (e.g., I liked/didn’t like a session/format/topic, etc.) Or they may discover that aspects that were negative for them were positive for others, or vice versa. Learning how your experience reflects that of the group is valuable information that leads to the consequence that…

I’m not sure there’s a faster way for a group’s members to learn about what they have in common. Rapidly uncovering and expressing thoughts and feelings about what they’ve experienced together creates powerful bonds. The intense experience makes it likely (though not assured) that the event participants will want to meet again. And the spective provides valuable clues as to what forms such meetings might take.

Spectives are simple to lead, fun, informative, and bonding. They end your event on a high note. So make them the closing session of every conference you create!

A hat tip to Nicole Osibodu and Kamryn Bryce for sparking me to write about the value of spectives, via their LinkedIn post (below) on how they use them at The Community Factory events!

Many meetings still focus on creating audiences rather than community. Yes, there’s a big difference. And not just at meetings. Here’s how Damon Kiesow, Knight Chair for Digital Editing and Producing at the Missouri School of Journalism, compares the concepts of community versus audience from a journalistic perspective.

Kiesow says:

Community does not scale.

Audience scales.

Community is decentralized for quality.

Audience is centralized for profit.

Community is generative.

Audience is extractive.

—Damon Kiesow, @[email protected], Mastodon toot on Nov 06, 2022, 10:37

Kiesow concisely sums up why the news business and the meeting industry concentrate on audience rather than community. When media and meeting owners focus on short-term interests—big circulations and audiences, leading to higher status and consequential larger profits at the expense of “consumers”—it’s understandable that building community plays second fiddle to chasing media visibility and large audiences.

Another media professional—journalist, professor, columnist, and author Jeff Jarvis—writes about similar themes. (These two quotes are from my posts on the parallels between the evolution of journalism and events (2015) and on the parallel missions of journalism and participant-driven and participation-rich events (2018).]

“What the internet changes is our relationship with the public we serve…What is the proper relationship for journalists to the public? We tend to think it’s manufacturing a product called content you should honor and buy…That’s a legacy of mass media; treating everybody the same because we had to…So we now see the opportunity to serve people’s individual needs. So that’s what made me think that journalism, properly conceived is a service.”

—Interview of Jeff Jarvis by David Weinberger

A new definition of journalism: “…convening communities into civil, informed, and productive conversation, reducing polarization and building trust through helping citizens find common ground in facts and understanding.”

—Jeff Jarvis, Facebook’s changes

Jarvis believes that journalism should serve people’s individual needs rather than manufacture content for the masses. In addition, journalism’s service should be about convening communities into civil, informed, and productive conversation.

I began my first book with the research finding (and common observation) that people go to conferences to network and learn.

My later books (and many posts on this site) have emphasized the superiority of active over passive learning. Active learning occurs almost exclusively in community. Creating community at conferences around participant-driven content, therefore, creates a far more effective learning and connection-rich environment. As Kiesow illustrates for journalism, emphasizing community over audience also pays rich dividends for meeting attendees.

This brings us to a key question that is rarely openly discussed: Whom are conferences for? For decades, I have been championing peer conferences, where participants own their conferences. When the attendees are the owners, meeting designs that build and support community are the obvious way to go.

But, all too often, attendees are not the conference owners. Such owners, whether they be individuals or for-profit or non-profit entities, rarely have the same objectives for the event as the attendees. Making money for themselves or their organizations, increasing their status by running large events, promoting the ideas of a few people, or influencing the direction of a cultural or industry issue are their primary goals. Supporting attendee learning and connection is a secondary consideration.

The largely silent battles being fought about the future of journalism and meeting design are strikingly similar. Both realms can learn from each other.

I’m sharing what I’ve learned (so far) here.

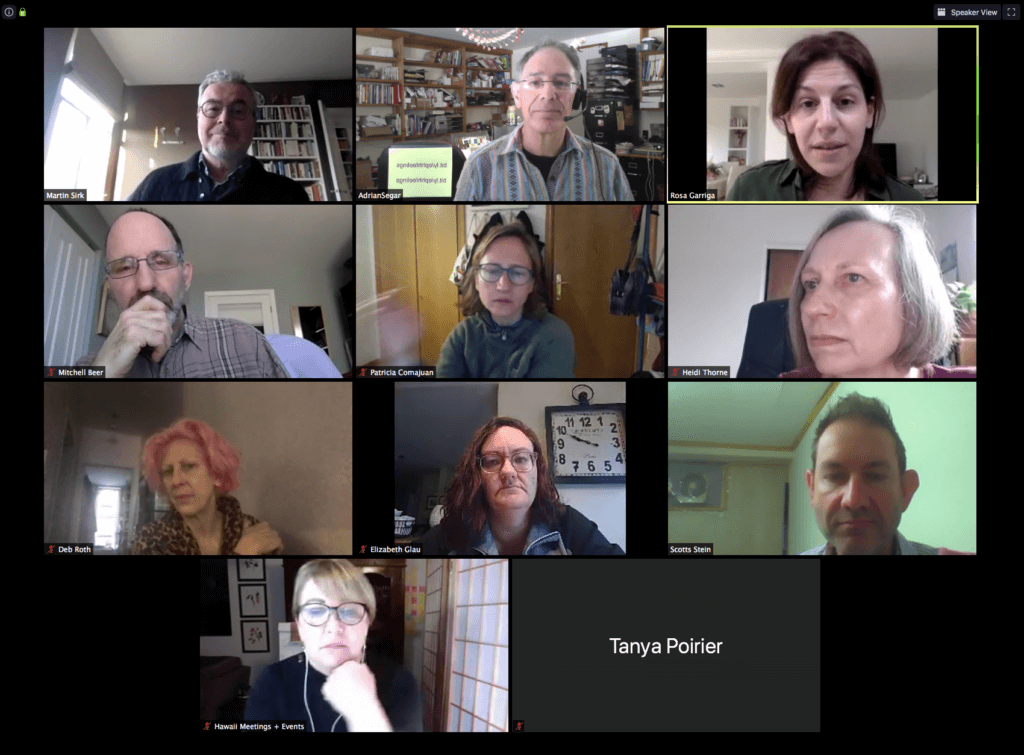

• Breakout room functionality is essential for your online meeting platform.

Small group conversations are the core components of successful online meetings. (If your meeting only involves people broadcasting information, replace it with email!) Unless you have six or fewer people in your meeting, you need to be able to efficiently split participants into smaller groups when needed — typically every 5 – 10 minutes — for effective conversations to occur. That’s what online breakout rooms are for. Use them!

• It’s important to define group agreements about participant behavior at the start.

For well over a decade, I have been asking participants to agree to six agreements at the start of meetings. Such agreements can be quickly explained, and significantly improve intimacy and safety. They are easily adapted to online meetings. (For example, I cover when and how the freedom to ask questions can be used when the entire group is together online.)

• Use a process that allows everyone time to share.

You’ve probably attended a large group “discussion” with poor or non-existent facilitation, and noticed that a few people monopolize most of the resulting “conversation”. Before people divide into small breakout groups, state the issue or question they’ll be discussing, ask someone to volunteer as a timekeeper, and prescribe an appropriate duration for each participant’s sharing.

• People want and need to share how they’re feeling up front.

I’ve found that pretty much everything important that happens at these meetings springs from people safely sharing at the start how they feel. They learn that they’re not alone. I ask participants to come up with one to three feeling words that describe how they’re feeling: either right now, or generally, or about their personal or professional situation. They write these words large with a fine-point permanent marker on one or more pieces of paper and share them, one person at a time, on camera or verbally. (Elaborations come later.)

• Sharing what’s working is validating, interesting, and useful.

In my experience, most people have made some changes in their personal and/or professional lives. Sharing these in small groups is a supportive process that’s well worth doing.

• Consultations are a powerful small group activity.

Set aside time, if available, for a few group consults on individual challenges. Ask for volunteers. They will receive support, and their small group of impromptu consultants will feel good about helping.

• Don’t forget to provide movement breaks.

Occasional movement breaks are even more important for online than face-to-face meetings. Participants can feel trapped sitting in front of their cameras. Schedule a break every 45 minutes.

• Check before moving on to a new topic.

If you are on video, ask for an affirmative sign (thumbs up or down), or use Roman voting. On audio, ask “Who has more to contribute to this?”

• Provide a set of tips and conventions for the online platform you’re using.

Here are mine for Zoom.

• Schedule time for feedback and/or a retrospective.

Key questions: What was this like? Do we want to do this again? If so, when, and how can we improve it?

Key information should be distributed appropriately well in advance of the meeting. Include it in a single online document, and create a descriptive URL shortened link (e.g. bit.ly/ephhfeelings). I suggest you share a short promo for your why? for the meeting, followed by this “complete details” link. Because many people don’t read the details until shortly before the meeting, resend your share closer to the time of the event.

I also like to display the link printed on a card visible in my video feed, so folks who have joined the meeting can catch up. Don’t rely on a chat window for this, since latecomers will not see earlier chat comments in most meeting platforms.

Here’s a sample of what you might want to include in your pre-meeting document for a 90-minute online meeting. My comments are in curly brackets {}.

[Date and start/end time of meeting]

[Time when the host will open online meeting] {I suggest opening the meeting platform at least 15 minutes before the meeting starts. This allows people, especially first-time users, time to get online}

The meeting starts promptly at [start time]

Please check out the following three links before the meeting:

Why you should attend [meeting title] {audience, rationale, agenda, etc.}

How to join this meeting {complete instructions on how to go online}

[Meeting platform] tips {make it easy for novices to participate — here are my Zoom tips}

Please have a few blank pieces of paper and a dark color fine point permanent marker (several, if you are artistically inclined). Before we start, write large on one piece of paper where you’re calling from. On another, please write (or illustrate) one to three feeling words that describe how you’re feeling: either right now, generally, about your personal or professional situation — you choose.

We will open the meeting at 11:45 am EDT.

Please join us before 12:00 if at all possible, so we can start together promptly. We’ll try to bring you up to speed if you join late, but it may be difficult if there are many already online and it will be disruptive for them.

The exact timings will depend on how many of us are present. This plan may change according to expressed needs. All times EDT.

11:45: Online meeting opens.

11:45 – 12:00: Join the meeting.

12:00: Meeting starts. Housekeeping. Where are you from?

12:05: Sharing our feelings words together.

12:10: Preparing for sharing what’s going on for you.

12:15: Sharing what’s going on for you in an online breakout room.

12:25: Group recap of commonalities and illustrative stories.

12:35: Preparing for sharing what’s helped.

12:40: Sharing what’s helped in the online breakout room.

12:50: Break — get up and move around! {Share your screen with a countdown timer displayed so people know when to return.}

12:55: Group recap of what’s helped.

13:05 Preparing for individual consulting. {Ask for a few volunteers.}

13:10: Individual consulting in an online breakout room.

13:25: Group recap of individual lessons learned.

13:35: Group feedback on the session. Do we want to do this again? If so, when, and how can we improve it?

13:55: Thanks and closing.

14:00: Online meeting ends.

Most online meetings do a poor job of maintaining participants’ attention. I’ve found that starting with a quick opportunity for people to share how they’re feeling effectively captures attendees’ interest. And using a platform and process that allows everyone time to share what’s important keeps participants engaged. You might get feedback like this…

“I just wanted to reach out again and thank you for the call today. What an incredible conversation spanning such significant geographical areas. The perspective we gain from discussion like today is priceless. I just got off of another call with [another community] and the vibe was completely different. While everyone was respectful, everyone’s overall sense of well being was generally pretty positive. And that’s where they wanted to keep it.”

—A participant’s message to me after an online meeting last week

Please try out these ideas! And share your suggestions and thoughts in the comments below.

“I am crazy but I’m not alone.”

—participant evaluation comment

Someone wrote “I am crazy but I’m not alone” on the paper evaluation form for the first edACCESS peer conference in 1992. The next year we printed it on a banner above the entryway to the event, and it’s been edACCESS’s official motto ever since.

There’s more behind this simple phrase than meets the eye.

We live in a culture that simultaneously values “being normal” while often glorifying those who are different. A long time ago, I concluded that this dissonance is reduced when you realize that, in reality, everybody’s weird in one way or another. Yes: you’re weird, I’m weird, everybody’s weird! (Don’t believe me? Introduce me to anyone I can communicate with, and I bet I can find something about them in five minutes or less that most people would think of as weird.)

When a group of people with something in common come together to share and learn, peer conferences like edACCESS allow people to discover that things that have been driving them crazy have been driving their peers crazy too. The relief of being in an environment where it’s safe to share what you thought was your craziness alone, and discovering that you’re not alone is immense!

And that leads to my preferred variant of this powerful motto.

How many times have you thought “This issue is important to me, but no one else seems to feel the same way.” or “Am I the only person who’s having trouble with this?” Perhaps you feel stupid, or out of touch with others, i.e. alone?

When you discover that challenges you thought were unique to you are actually shared and validated by peers, you realize “I’m not crazy! Here is a community that is having similar experiences to me! I’m not alone!”

The beauty of “I’m not crazy” is that it redefines your very-real weirdness as normal, because everybody’s weird. This frees you up to work on being who you are, rather than focussing negatively on what makes you different.

And that’s a good thing.

Sadly, many so-called experiential events are phony. The promoters slap a novel environment (e.g., clowns walking around or chairs suspended from the ceiling) onto a conventional format (e.g., a social or a group discussion) and claim their event is now “experiential”.

So what are the differences between genuine and phony experiential conferences?

Here are three.

At a genuine experiential conference…

People attend conferences to learn and connect. They arrive with specific personal challenges for which they hope to get help and support. For example,

“I’m having a hard time handling my boss’s unrealistic expectations of what I can accomplish.”

“Our security system needs an upgrade and I’m overwhelmed by the choices available.”

“Are there other people here with whom I can explore how AR is going to impact our jobs?”

Hiring clowns to walk around and entertain attendees or immersing attendees in an elaborately themed environment does nothing to help attendees learn and connect around the issues and topics that matter to them. (Rare exception: an environment designed to dramatize and support the exploration of known concerns.)

Uncovering participants’ challenges, interests, expertise, experience, and passions early at the event and then building conferences that respond directly leads to genuine experiential conferences that effectively satisfy attendee needs.

If you go to a professional conference and nothing significant changes in your professional life as a result, what was the point of attending? Yes, you might have had a good time and been entertained, but you can get that faster and cheaper by eating out at a great restaurant, watching a good movie, or attending a show or concert. (And “I had a great time” is likely not the kind of justification for attending your boss wants to hear.)

Design genuine experiential conferences to deliver experiences that change professional lives by:

“Experiential” event programs today feature “experiences” like SoulCycle, axe throwing, and wine tastings. Sessions like these are, of course, experiences — as is all of life. What such sessions fail to do is build any kind of event community around the theme or constituency of the conference. So, at a phony experiential event, having a good time with colleagues qualifies the event as “experiential”.

In contrast, genuinely experiential conferences include group experiences that deepen learning and connection around pertinent material, and, in the process, build community that speaks to the wants and needs of the participants.

Examples? Hold sessions where attendees work together to solve carefully chosen topical or individual challenges. Or, include a closing session where participants share what was great about the entire event and how it could be made even better.

Putting attendees in a novel environment does not make a meeting “experiential”. Genuine experiential events use active uncovered learning formats that maximize the likelihood of meaningful learning and connection for each attendee.

There’s nothing wrong with razzle-dazzle environments, except when they (all too often) divert money, energy, and focus from what’s important. Instead, concentrate time and resources on functional meeting design that provides genuinely useful and meaningful experiences to participants.

Such a transformation is the essential work that we need in order to build a human community around the event. It becomes something special, standing out like a beacon from the humdrum conferences routinely inflicted on attendees.

The meeting feels different, is different, because it allows participants to be truly heard and seen. Because having people listen to us is a gift. And, as Seth Godin puts it:

“We like to see. But mostly, we’re worried about being seen…the culture of celebrity that came with TV has shifted. It’s no longer about hoping for a glimpse of a star. It’s back to the source–hoping for a glimpse of ourselves, ourselves being seen.”

—Seth Godin, Mirror, mirror

It takes a few minutes at the start of a gathering to create agreements that help make it a safe place for participants to:

Immediately, the conference is subtly different, full of new possibilities, some of which might have been considered risky or even taboo. Everyone in the room begins to learn about each other in ways that matter. Everyone begins to discover how they can become a part of the gathering, how they can contribute, and how they can learn about issues and challenges that personally matter.

Make it easy for participants to be safely and truly heard and seen. Your conferences will be all the better for it.

Image attribution: Flickr user paris_corrupted

“…convening communities into civil, informed, and productive conversation, reducing polarization and building trust through helping citizens find common ground in facts and understanding.”

—Jeff Jarvis, Facebook’s changes

That sounds a lot like the mission of the participant-driven and participation-rich events I’ve been championing for so long. Journalism can’t provide the connective power of face-to-face meetings. But its potential for helping individuals and communities build trust and find common ground is worthy and welcome.

Image attribution: Nectar Media