Resolutions rarely work

“…if you make a resolution, you should formulate it so that at every point in time it is absolutely clear whether you are sticking to it or not. The clear lines are arbitrary, but they help the truce between our competing interests hold.”

I explained how this shapes my design for a closing session that supports participants making changes in their lives, based on what they’ve learned and the connections they’ve made at an event.

In this post, I’ll share a couple of additional perspectives about making resolutions.

Seth Godin on resolutions

First, there’s the inimitable Seth Godin. In December 2020, Seth posted this:

Over the next few weeks, there may be fewer urgencies than usual. That’s the nature of coming back from a break.

What if we used the time to move system deficiencies from the “later” pile to the “it’s essential to do this right now” pile?…

…Resolutions don’t work. Habits and systems can.

—Seth Godin, A different urgency

In his post, Seth suggests that one way to handle the “urgent” tasks that fill our lives is to create and fix systems that reduce our desire and need to make resolutions. We rarely do this because:

“Most of us are so stuck on the short-cycles of urgency that it’s difficult to even imagine changing our longer-term systems.”

But if we do…

“Amazingly, this simple non-hack (in which you spend the time to actually avoid the shortcuts that have been holding you back) might be the single most effective work you do all year.”

Deborah Elms on eliminating resolutions

My longtime friend Deborah Elms, has another take on resolutions—eliminate them altogether.

Thinking about resolutions for 2023?

Personally, I long ago replaced resolutions with intentions:

#Resolutions are based in our superego beating up on us for being “wrong” or deficient somehow. And we may try for a few days or weeks and then end up ignoring or fighting the resolutions.

#Intention, on the other hand, just recognizes and empowers a direction we’d like to take our life. No bullying!

“I resolve to never eat crap” (yeah right)

vs

“I intend to eat healthier” (ok, can do)

—Deborah Elms, Mastodon post

I’ve written about my attempts to build good habits and described some of the ways I’ve been successful. But I haven’t said much about the frequently significant emotional cost of (sometimes years of) attempts to make such changes in one’s life.

Deborah’s suggestion probably won’t make it easier to create the change that a (rarely) successfully kept resolution might make. But it will reduce your beating up yourself emotionally during the struggle to make the change.

And improving your peace of mind in this way can be worth a lot.

To conclude, although, resolutions rarely work…

…you can:

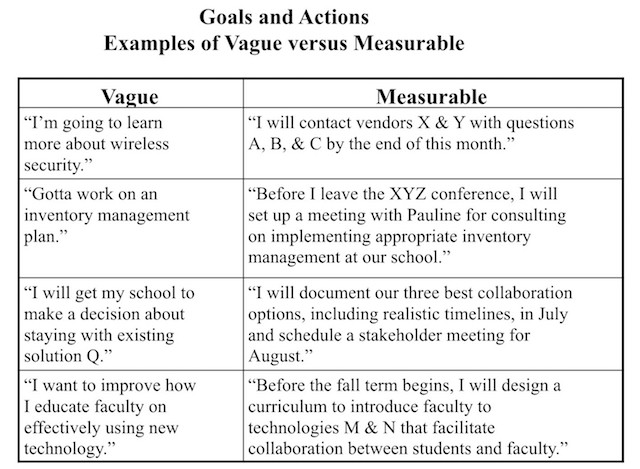

- Maximize the likelihood they will by making them measurable rather than vague;

- Reduce the need for resolutions by implementing longer-term systems that handle frequent urgent problems; and

- Change them into intentions that lower the emotional stress you feel while you’re trying to implement the change.

Do you have thoughts about the value and implementation of resolutions? If so, please share them in the comments below!

Image attribution: minifigs.me

Understanding the psychology of motivation can help us create better event outcomes. I’ll illustrate with a story about unusual traffic on this very website…

Understanding the psychology of motivation can help us create better event outcomes. I’ll illustrate with a story about unusual traffic on this very website…