The Future Of Conferences Is Unconferences

Meetings and conferences are perhaps one of the most important fundamental ways in which people come together and change happens. Yet this topic is rarely the focus of much academic study. So I’m pleased to discover an academic research article paper about unconference — especially since its title is: The Future Of Conferences Is Unconferences! The paper appears in the October 2023 issue of the venerable Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) Interactions journal. ACM is the world’s largest educational and scientific computing society.

Meetings and conferences are perhaps one of the most important fundamental ways in which people come together and change happens. Yet this topic is rarely the focus of much academic study. So I’m pleased to discover an academic research article paper about unconference — especially since its title is: The Future Of Conferences Is Unconferences! The paper appears in the October 2023 issue of the venerable Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) Interactions journal. ACM is the world’s largest educational and scientific computing society.

Now, I’m not a fan of the term “unconference” because:

- In many ways, unconferences were originally and now should be what are called conferences today; and

- The term “unconference” is now often used indiscriminately, typically as a hip description of events that don’t determine their programs in real-time.

Nevertheless, I’m happy that at least some in academia see the value of participant-driven and participation-rich conferences.

Here’s a summary of the paper [read and/or download the full paper here].

The Future Of Conferences Is Unconferences

The paper begins with a critique of traditional conferences that will be familiar to regular readers of this blog: one-sided communication, high costs, environmental impact, and time away from other obligations.

Consequently the authors propose a new model: locally grouped unconferences, that prioritize informal connections and participant-driven content over formal presentations, challenging the hierarchical structure of conventional conferences.

An unconference-style event for local researchers

To assess the feasibility of this model for academic research, a group of researchers in the northeastern U.S. organized an unconference-style Computer-Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW) event for local researchers. This event was free to attend and focused on interactions between researchers, with an emphasis on dynamic and meaningful interactions.

This one-day event was restricted to 70 participants, and included World Café and three 45-minute panel sessions, each featuring four panelists presenting their research findings. The panel sessions received positive feedback, though some participants noted challenges in selecting panelists and finding relevant papers for discussion.

The World Café table topics and the panelists were chosen in advance, so this wasn’t really a true unconference. However, participants reported “unanimous satisfaction”, “making meaningful connections”, and “interest in attending future similar events”.

The key elements of the unconference program included socialization, dissemination, and event organization. Socialization activities, such as an icebreaker and World Cafe-style discussions, were highly appreciated by participants for promoting engagement. However, they were less effective at identifying collaboration opportunities. [The peer conferences I’ve been running since 1992 are far more effective in this regard.] Participants found the smaller size of the event and unstructured socializing to be conducive to meaningful connections.

Size and location

The authors say that the size and location of the event are crucial. A right-sized event allows for meaningful networking without overwhelming attendees. Participants expressed a willingness to travel to other locations, provided they were easily accessible. They proposed that regional meetups should occur between quarterly and biannually to provide more regular contact with researchers. They should complement official conferences rather than compete with them. The goal is to make conferences more accessible and enjoyable, especially for junior scholars and those with fewer resources.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the paper states that a decentralized regional meetup model offers a promising alternative to traditional academic conferences. Its cost-effectiveness, emphasis on interactions, and potential for more regular contact among researchers make it a valuable addition to the academic conference landscape.

The authors believe that the success of this local unconference model suggests it can mitigate the drawbacks of traditional conferences. To promote more local gatherings, organizers can leverage the lower cost and preparation time of such events. They can also create a portal for organizers to share their experiences and knowledge, enabling others to learn from their experiences.

The authors offer these key insights:

- A localized unconference model for academic conferences can serve as a viable alternative to mitigate the inherent drawbacks of conventional conferences.

- Key to the success of such regional meetups is lower friction of organizing.

- Such regional meetups should focus more on interactions between researchers than the dissemination of knowledge.

—Soya Park, Eun-Jeong Kang, Karen Joy, Rosanna Bellini, Jérémie Lumbroso, Danaë Metaxa, Andrés Monroy-Hernández , The Future Of Conferences Is Unconferences

Software testers do peer conferences right! (They even call them a peer conference, rather than unconference, a term I

Software testers do peer conferences right! (They even call them a peer conference, rather than unconference, a term I  The words we use for meetings matter. Unfortunately, familiar terms often perpetuate conventional meeting thinking. By changing the words we use, we can change how we think about events. Here are three examples of better words to use when talking about meetings.

The words we use for meetings matter. Unfortunately, familiar terms often perpetuate conventional meeting thinking. By changing the words we use, we can change how we think about events. Here are three examples of better words to use when talking about meetings.

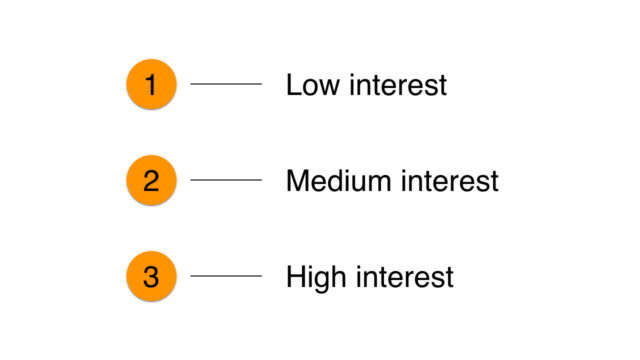

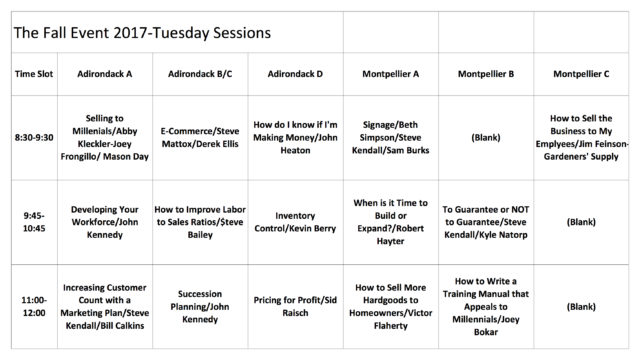

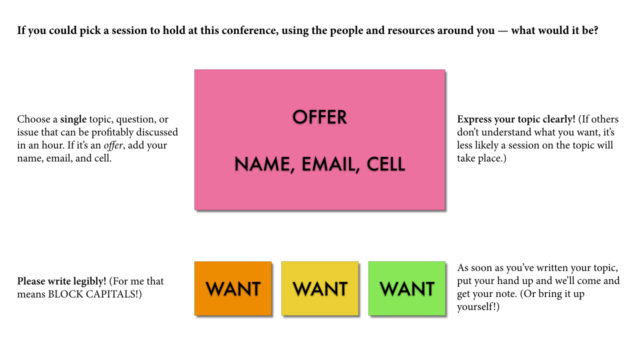

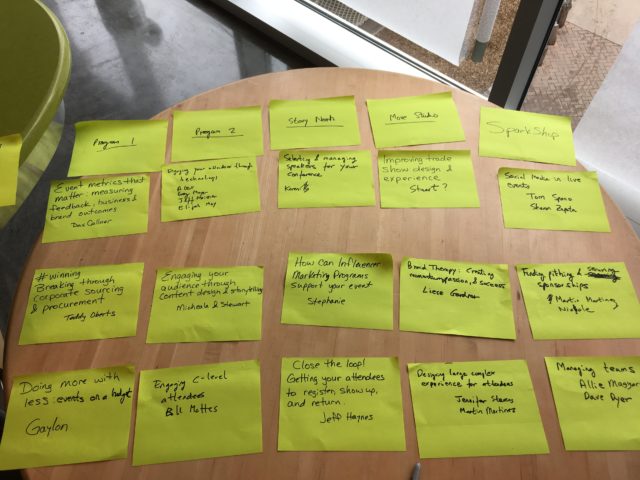

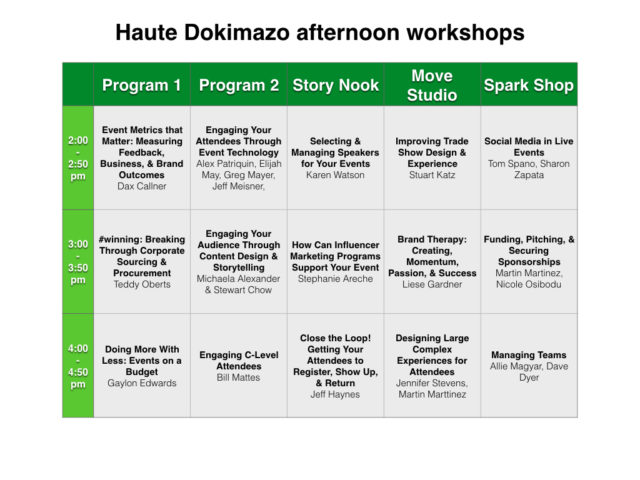

How do we build conference programs that attendees actually want and need? Since 1992 I’ve experimented with multiple methods to ensure that every session is relevant and valuable. Here’s what happened when I incorporated dot voting into a recent two-day association peer conference.

How do we build conference programs that attendees actually want and need? Since 1992 I’ve experimented with multiple methods to ensure that every session is relevant and valuable. Here’s what happened when I incorporated dot voting into a recent two-day association peer conference.

Here’s a 22-second video excerpt of the dot voting, which was open for 35 minutes during an evening reception.

Here’s a 22-second video excerpt of the dot voting, which was open for 35 minutes during an evening reception.

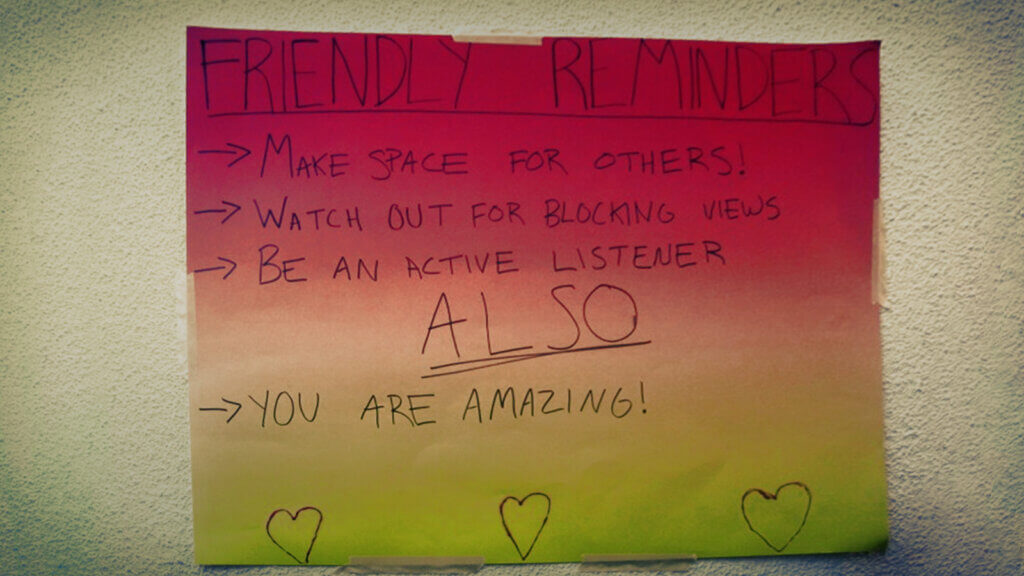

Ground rules? We don’t need ’em!

Ground rules? We don’t need ’em!