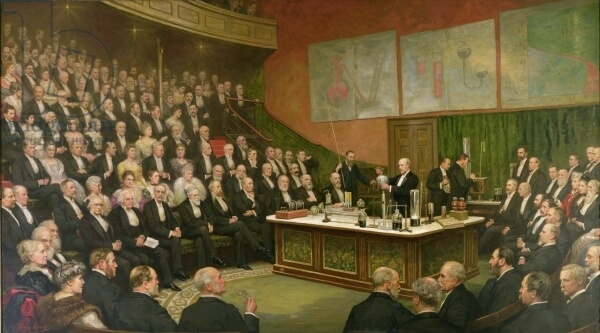

Are science conferences stuck in the Dark Ages?

An article in Wired argues that “Science Conferences Are Stuck in the Dark Ages“. Unsurprisingly, I agree — but there’s some light in the darkness!

Here are some of the points scientists Esther Ngumbi and Brian Lovett make in the article. Many will be familiar to my readers:

“…for decades, whether in Basel or Bolivia, the room has been the same: four walls, a podium, and a projector.”

“Where’s the dialog? Where’s the questioning? Where’s the innovation?”

“And what about the dry format? Does the predominant stream of posters and lectures still benefit science? Why the deluge of printed posters when we are battling climate change? Why an onslaught of 10-minute presentations and only a few slots for a robust discussion?”

“…it is easy to accept the status quo, especially if there are no immediate consequences for not changing. Unlike teaching, where we have real consequences when we fail to modernize, such as poor evaluations and losing enrollment, there are no real consequences for the professional societies organizing the meetings or for presenting scientists.”

A positive trend

After these tales of woe, Esther and Brian share a positive trend:

“The good news is that researchers, professional societies, and conference organizers are beginning to ponder on these questions.

The ‘unconference’ is one of the modern-day conferences that reflects a step in the right direction. In this format, delegates from diverse research fields set the agenda, not the conference organizers themselves. Also, because delegates set the agenda, everyone’s voice is included.”

As you probably know, I’ve been designing and facilitating unconferences for decades (though I prefer to call them peer conferences.) The key, but often unappreciated, strength of peer conferences is that the agenda is determined at the event rather than beforehand.

“Presentations of the future should include anonymous evaluations.”

I’m not sure how helpful this suggestion is, even though I suspect session evaluations are rare at science conferences. Most conferences these days include anonymous session evaluations. Unfortunately, such evaluations have very little (or even worse, misleading) impact on session selection at future events.

A vision for a better conference

“…a more perfect conference would look like this: …you arrive at a conference where everyone’s voice and ideas were included in determining the agenda. And because you feel included you are motivated to actively participate. The presentations are robust, interactive, and full of dialog. Time slots aren’t organized by scientist, but by scientific goals shared by interdisciplinary scientists. And because the presentation is interactive you come away from the presentation with new understanding of our momentum toward solving that societal problem.”

Over the years, I’ve designed successful conferences for many different kinds of organizations that incorporate all these desirable attributes. We know how to do this! Similar designs for academic conferences are less common, though I’ve consulted on the design and improvement of science conferences for clients like The Nature Conservancy and the American Heart Association.

Finally, the authors, suggest:

“Perhaps it’s time for a conference reimagining the conference format for the new decade.”

Well, Esther and Brian, my Participate! Labs are exactly what you’re asking for! I’m also a fan of the Meeting Design Practicum, an annual invitation-only European conference for meeting designers, which I’ve attended every year since it began in 2016.

Conclusion

Yes, most science conferences are stuck in the Dark Ages. The good news is that there’s plenty of light available if you know where to look. I hope that this blog and my books provide strong illumination, available to anyone who wants to improve their conferences.

[HT to Heidi Thorne who shared this article with me.]