Meeting room designs for both in-person and remote participants

Now that small hybrid meetings are commonplace, what meeting room designs work for a mixture of in-person and remote participants?

Read the rest of this entry »

Now that small hybrid meetings are commonplace, what meeting room designs work for a mixture of in-person and remote participants?

Read the rest of this entry »

When the COVID-19 pandemic began, in-person meetings vanished overnight. Suddenly Zoom became a household word. If we couldn’t safely meet face-to-face, we’d sit in front of screens.

But what should we call these internet-mediated meetings?

In July 2020, I suggested that we not call them virtual meetings. Instead, I made the case to use the word online. In essence, I pointed out that virtual has the connotations of “not quite as good” and unreal, while online is a neutral and well-established description of the meeting medium. Read the post for a detailed argument.

Though I don’t claim any credit, I’m happy to observe that meeting industry professionals and trade journals currently tend to prefer “online meeting” to “virtual meeting,” though there are some notable exceptions. Google also shows the same preference, with 5.0B search results for “online meeting” versus 1.3B for “virtual meeting.”

This is a big one and a harder switch to make. The word networking has been used so often to describe what people do at meetings that it’s tough to supplant. But describing everything that happens outside event sessions as networking subtly directs attention away from what can be the most valuable outcome of well-designed meetings: connecting with others.

We’ve biased how we talk about connection at meetings by using a word that is much more focused on personal and organizational advantage than personal and professional mutual benefits.

I lightheartedly titled my recent post on this topic, “Stop networking at meetings“. But it’s a serious suggestion. Having a mindset of encouraging and supporting connection around useful content plus a set of meeting process tools that can make it happen is a game-changer for meeting effectiveness.

Sadly, I’m a voice in the wilderness on this one. 13 years ago, I wrote Why I don’t like unconferences. As I explained in my first book, Conferences That Work, what people call an unconference is what a good conference should actually be. At unconferences, far more conferring goes on than at traditional events. I coined the term peer conference as an attempt to remove the “un” from “unconference”.

I was ignored.

This linguistic problem worsened as people decided that calling traditional events “unconferences” made them sound cool. They ignored the central feature of an unconference; that sessions are chosen at the event rather than scheduled in advance. These days I frequently see advance calls for speaker submissions at meetings advertised as “unconferences”! You even find traditional breakout sessions described as unconferences, presumably because more than one person might speak. I cover these depressing developments in These aren’t the unconferences you’re looking for.

Today, “peer conferencing” is principally used to describe an educational approach to writing in groups. So I’ve reluctantly given up trying to swim against the tide and have been using the term unconference in my recent writing.

C’est la vie.

The words we use for meetings matter. My little campaigns to reframe some language the meeting industry uses have had mixed results. What do you think of my suggestions? Are there other examples of meeting industry language you’d like to see changed? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Apropos of nothing, here, in alphabetical order, are some meeting industry terms I like. Don’t ask me why.

The first novel hybrid meeting format was invented by Joel Backon back in 2010. The second is a design I’ll be using in a conference I’ve designed and will be facilitating in June 2022.

Back when hardly anyone used the term “hybrid” for a meeting, let alone participated in one, I had the good fortune to participate in a novel session “Web 2.0 Collaborative Tools Workshop” designed by Joel Backon at the 2010 annual edACCESS conference. During the session, all the in-person participants had an online experience, followed by an in-person retrospective. The online portion felt eerie…

“Some participants had traveled thousands of miles to edACCESS 2010, and now here we were, sitting in a theater auditorium, silently working at our computers.”

—Adrian Segar, Innovative participatory conference session: a case study using online tools, June 27, 2010.

Check out my original post for the details of the session, which explored the unexpected advantages of working together online even when the participants are physically present. The experience certainly opened my eyes to the power of collaboratively working on a time-limited project using online tools.

You can use this novel hybrid meeting format to explore the effectiveness of employing appropriate online tools to work on problems at an in-person event. Following up the exercise with an immediate in-person retrospective uncovers and reinforces participants’ learning.

These days it’s even easier to implement similar hybrid sessions at in-person meetings. Participants will learn a lot while exploring the advantages and disadvantages of collaborating online!

As I write this I’m designing a one-day, in-person peer conference for 150 members of a regional association. As readers of my books know, running a peer conference for this many people in one day would be a somewhat rushed affair. Unfortunately, the association practitioners simply couldn’t take off more than a day to travel to and attend the event.

Squeezing The Three Questions, session topic crowdsourcing, the peer sessions themselves, and at least one community building closing session into a single day is tough. In addition, the time pressure to quickly crowdsource good sessions and find appropriate leadership is stressful for the small group responsible for this important component.

To relieve this pressure I’ve designed a hybrid event that once again uses the same participants for both the online and in-person portions.

The day before the in-person meeting, participants will go online briefly twice, in the morning and in the afternoon. During the morning three-hour time slot, participants can suggest topics for the in-person conference. We’ll likely use a simple Google Doc for this. They will be able to see everyone’s suggestions and can offer to lead or facilitate them.

Around lunchtime, a small group of subject matter experts will clean up the topics. Then, during the afternoon three-hour time slot, participants will vote on the topics they’d like to see as sessions the following day. The evening before the conference, the small group will convene and turn the results into a tracked conference program schedule that reflects participant wants and needs. They will also decide on leadership for each session. (Read my book Event Crowdsourcing to learn in detail how to do these tasks.)

Moving the program creation online the day before the in-person event allows participants to spend more time together in person. This choice sacrifices the rich interactions that occur between participants during The Three Questions. But in my judgment, the value of creating a less rushed event in the bounded space of a single day is worth it.

[Want to read my other posts on hybrid meetings? You’ll find them here.]

I believe we’ve barely started to explore the capabilities of hybrid meeting designs. Including both online and in-person formats in a single “event” multiplies the possibilities in time and space. I’m excited to see what new formats will appear in the future!

Have you experienced other novel hybrid meeting formats? Share them in the comments below!

“It was rare, I was there, I remember it all too well.”

Listening to Taylor Swift’s lament in her beautiful and evocative “All Too Well: The Short Film” I feel my own grief well up. My last in-person engagement was a wonderful two-day workshop with several hundred cardiologists in Texas. January 28 and 29, 2020. As I’m writing this, that was twenty-two months ago.

Since then, I’ve worked with many groups online. But it’s not the same.

I’m sure you can relate. Yes, it’s wonderful to be instantly connected, with video and sound, to like-minded folks, friends, and family scattered around the country or globe. So much better than the only option in my youth — the telephone. Long-distance phone calls then cost so much that speaking to someone far away or, heaven help us, internationally was a rare treat.

But it’s not the same.

I miss doing what I love to do. Facilitating connection between people around what matters to them. Creating meetings that become what the participants want and need. The magic of the unexpected that appears when you least expect it, and, sometimes, changes peoples’ lives.

Yes, that magic can and does happen online. But, in my experience, it’s much rarer.

Online, we meet using group-focused platforms that don’t have the power, nuance, and flexibility of in-person meetings.

The platforms themselves impose additional restrictions. In Zoom, for example:

Online social platforms can provide an experience much closer to that of an in-person social. Participants can see who’s “in the room” and decide whom to talk with, either one-to-one or small group, in public or private. In the last couple of years, I’ve enjoyed holiday parties with folks who could never have practically got together in person, and these platforms are well worth exploring if you haven’t already.

But it’s not the same as hanging out with and making new friends in person.

And we’re back to the grief. “It was rare, I was there, I remember it all too well.” I see a photo of a meeting I attended with so many friends, and I miss them, and wonder if/when I’ll see them again in person rather than on a screen.

I feel it. It’s good to remember the past, to feel the pain of its absence now, to be in touch with it, to acknowledge its presence. And then I return to working on being in the present, with my grief a part of me.

Ever since my first encounter with the hybrid hub and spoke meeting topology at Event Camp Twin Cities in 2011, I’ve been a big fan of the format. Yesterday [see below], I realized that hub and spoke is a great format for purely online meetings too. But first…

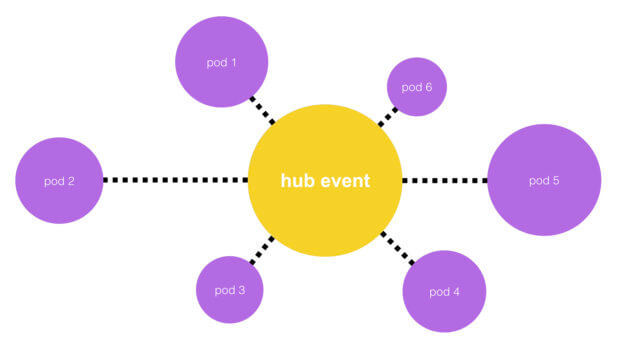

A hub and spoke meeting is one where there’s a central hub meeting or event that additional groups (aka “pods”) of people join remotely.

A terminology reminder

In-person meeting: participants are physically together.

Online meeting: participants are connected to each other via an internet platform like Zoom or Teams.

Hybrid meeting: A meeting with in-person and online components as defined above, plus additional forms explored below.

If you want maximum learning, interaction, and connection at a meeting, small meetings are better than large meetings. Using good meeting design, simply splitting a single large group of participants into multiple small groups in an intelligent way provides increased opportunities for each group’s members to connect and interact around relevant content.

Hub and spoke topology allows tremendous design flexibility for a meeting.

In-person pods can be set up at any convenient geographical location, reducing travel time and costs for pod participants while still providing the benefits of in-person interaction.

You can segment online pods to reflect specific “tribes”: groups of people with something in common. For example, think about a conference to explore the implications of a medical breakthrough. One pod could be for patient groups that the discovery will affect. Another might include medical personnel able to deliver the new technology or procedure. Yet another group could contain scientists working on the next iterations. [A hat tip to Martin Sirk for suggesting this example!]

Creating pods that reflect event participant segments allows different communities’ goals and objectives to be optimally met while sharing with all participants a common body of learning and experiences via the hub.

As noted above, using in-person pods can dramatically reduce the travel time and cost for event participants without sacrificing the benefits of meeting in person. This allows more people to attend the hub and spoke meeting, and makes it easier for them to do so.

Depending on the choices made, a hub and spoke event will take one of the following forms:

This is the classic hybrid hub and spoke format that we used 14 years ago at Event Camp Twin Cities (ECTC).

Here’s a little information about the groundbreaking ECTC. Besides the attendees at the in-person hub event in Minneapolis, seven remote pods in Amsterdam, Philadelphia, Toronto, Vancouver, Silicon Valley, and two corporate headquarters were tied into a hub feed that—due to the technology available at the time—was delayed approximately twenty seconds. As you might expect, this delay led to several communication issues between the hub and pods. I wrote about ECTC in more detail here.

There will always be some communications delay between the hub and pods, though these days it can be reduced to a fraction of the delay at ECTC. Such delays should be taken into account when designing hub and spoke events.

My recent experience of being in an online pod viewing an online hub event made me realize that online pods can be used to great effect with either in-person or online hub events.

Since February 2021, my friend, tech producer, and meeting industry educator Brandt Krueger has been hosting weekly EventTech Chats on Zoom, together with another friend, his talented co-host, “The Voice of Events”, Glenn Thayer. Yesterday, Brandt was presenting at an MPI event on hybrid meetings, so Glenn shared the event so we could kibitz. Seven of us were in a Zoom, watching a Zoom…

I commented about the recursive nature of this…

On a small group Zoom, watching a meeting industry Zoom panel. (Kinda nice, as our group can comment in our Zoom on what we’re watching.) This could be extended.

Is there a Guinness World Record for the number of Zooms watching another Zoom watching another Zoom…? pic.twitter.com/rwNmQFFdWJ

— Adrian Segar (@ASegar) July 16, 2021

…and Anh Nguyen replied that the experience was like Inception. She also mentioned Giggl, which, similarly, allows a group to interact (text and voice) on a shared internet portal. This could be useful if you don’t have a Zoom license.

The MPI meeting had over 150 viewers. We noticed that there was little interaction on the MPI Zoom chat. Our little group was much more active on chat. We were a small group with a common set of interests, and we all knew each other to some extent.

It’s clear to me that we had a much more interactive, useful, and intimate discussion than the hub event group.

Yes, this is one anecdotal example. But I hope you can see how being in a small pod of connected folks can lead to a better experience than being one of many attending the same event at a hub.

The ease, with today’s technology, of creating an online pod with whomever you please to watch and comment on a hub event, makes this an attractive option for attending the hub event directly online. (If you wanted to, of course, you could do both—as Glenn Thayer did for our pod.)

Finally, there’s no reason why a hub event can’t support a mixture of in-person and online pods. (In fact, ECTC had a small number of individual remote viewers as well, though I suspect they could only watch the hub stream.) Once the hub stream is available, one can share it with an online pod, or on a large screen with an in-person pod. Mix and match to satisfy event stakeholders’ and participants’ wants and needs!

I believe that hybrid meetings, catapulted into industry awareness by the COVID-19 pandemic, will be a permanent fixture of the meeting industry “new normal”. Once we’ve firmly established the design and production expertise needed for hybrid, hub and spoke is a simple addition that promises the many advantages I’ve described in this post.

It may take a while, but I think we are going to see a growing use of this exciting and flexible format.

What do you think about hub and spoke meetings? Have you experienced one, and, if so, what was it like? Do you expect to use this format in future events? Share your thoughts in the comments below!

And, like Colin Smith, the protagonist (played by Tom Courtney) of the classic 1962 film The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner, I sometimes feel alone.

Meeting via Zoom is far better than not meeting at all, but it doesn’t compare with being with people face-to-face.

I love to facilitate in-person meetings, and I miss the personal connection possible there.

But even when I facilitate in-person meetings, there are times I feel lonely. No, not while I’m working! Not when I work with clients to design great meetings, create safety, uncover participants’ wants and needs, moderate panels, crowdsource conference programs and sessions, facilitate group problem-solving, and run community-building closing sessions.

But there are times during the event when I’m not working. While the sessions I helped participants create are taking place. During breaks when I’m not busy preparing for what’s to come. And during socials.

At these times, I feel a bit like The Invisible Man.

Why? Because, though I may have facilitated and, hopefully, strengthened the learning, connection, and community of participants present, I’m not a member of the community.

In the breaks and socials, I see participants in earnest conversations, making connections, and fulfilling their wants and needs in real-time. But I’m hardly ever a player in the field or issues that have brought them together. (Usually, as far as the subject matter of the meeting is concerned, I’m the most ignorant person present.) So I don’t have anyone to talk to at the content level. I’m physically present, but I don’t share the commonality that brought the group together. It’s about participants’ connection and community, not mine.

I may have made what’s happening better through design and facilitation, but it’s not about me.

Every once in a while, participants notice me and thank me for what I did. It doesn’t happen very often—and that’s OK. My job is to make the event the best possible experience for everyone. My reward is seeing the effects of my design and facilitation on participants. If I were doing this work for fame or glory, I would have quit it long ago.

If you’re at a meeting break or social and see a guy wandering around who you dimly remember was up on stage or at the front of the room getting you to do stuff?

It’s probably me.

Paradoxically, when I facilitate online meetings there’s no “invisible man” lonely time. Whenever we aren’t online, we’re all alone at our separate computers. We can do whatever we please. We were never physically together, so we don’t miss a physical connection when we leave.

The loneliness of the long-distance facilitator is accentuated at in-person events by the abrupt switches between working intimately with a group and one’s outsider status when the work stops.

At online events, we are all somewhat lonely because no one else is physically present. Our experiences of other people are imperfect instantiations: moving images that sometimes talk and (perhaps?) listen.

It wouldn’t be a no-brainer choice, but if I had to choose between facilitating only in-person or online meetings, I’d choose the former. The intimacy of being physically together with others is worth the loneliness when we’re apart.

Image from The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner

“Often wondered why so many on this feed hate live events.”

“It is my opinion that this group does not support any in-person meetings or gatherings of any kind…”

” I am sad to see so many industry giants verbally destroying our industry – apparently with glee.”

Let’s explore what’s causing opinions and feelings like this in the meeting industry.

As I’ve said before, the pandemic’s impact on lives and businesses has been devastating, especially for the meeting industry. COVID-19 has virtually eliminated in-person meetings: our industry’s bread and butter. Many meeting professionals have lost their jobs, and are understandably desperate for our industry to recover. We are all looking for ways for in-person meetings to return.

Unfortunately, I and many others believe there is a strong case to make against currently holding in-person meetings. Ethically, despite the massive personal and financial consequences, we should not be submitting people to often-unadvertised, dangerous, and life-threatening conditions so we can go back to work.

I’ve been posting bits and pieces of the case against currently holding in-person meetings on various online platforms and decided it was time to bring everything together in one (long for me) post. I hope many meeting industry professionals will read this and respond. As always, all points of view are welcome, especially those that can share how to mitigate any of the following concerns.

Here are four important reasons why I think we shouldn’t be holding “large” in-person meetings right now. (Obviously, “large” is a moving target. Checking Georgia Tech’s COVID-19 Event Risk Assessment Planning Tool as I write this, a national US event with 500 people is extremely likely (>95%) to have one or more COVID-19-positive individuals present.)

Seven months ago, I explained why, in my opinion, in-person meetings do not make sense in a COVID-19 environment. I assumed that in-person meetings could, in principle, be held safely if everyone:

Even if one could meet these difficult conditions, I questioned the value of such in-person meetings. Why? Because meetings are fundamentally about connection around relevant content. And it’s impossible to connect well with people wearing face masks who are six or more feet apart!

In addition, there’s ample evidence that some people won’t follow declared safety protocols. Since I wrote that post, we have heard reports and seen examples of in-person meetings where attendees and staff are not reliably social distancing, and/or aren’t wearing masks properly or at all.

This is most likely to happen during socials and meals, where attendees have to temporarily remove masks. It’s understandably hard for people to resist our lifetime habit of moving close to socialize.

Many venues trumpet their comprehensive COVID-19 cleaning protocols. Extensive cleaning was prudent during the early pandemic months when we didn’t know much about how the virus spread. But we now know that extensive cleaning is hygiene theater (1, 2); the primary transmission vector for COVID-19 is airborne.

A recent editorial in the leading scientific journal Nature begins: “Catching the virus from surfaces is rare” and goes on to say “efforts to prevent spread should focus on improving ventilation or installing rigorously tested air purifiers”.

I haven’t heard of any venues that have publicly explained how their ventilation systems minimize or eliminate the chance of airborne COVID-19 transmission!

Why? Because it’s a complicated, and potentially incredibly expensive issue to safely mitigate. And venues are reluctant or unable to do the custom engineering and, perhaps, costly upgrades necessary to ensure that the air everyone breaths onsite is HEPA-filtered fast enough to keep any COVID-positive attendee shedding at a safe level.

Adequate ventilation of indoor spaces where people have removed masks for eating or drinking is barely mentioned in governmental gathering requirements (like this one, dated March 3, 2021, from the State of Nevada). These guidelines assume that whatever ventilation existed pre-COVID is adequate under the circumstances, as long as all parties are socially distanced. We know from research that there are locales — e.g. dining rooms with low ceilings or inadequate ventilation — where this is not a safe practice, since it’s possible for COVID-carrying aerosols to travel far further than 6 feet.

In case you are interested, current recommendations are for MERV 13 filtering throughout the venue. Does your venue offer this?

P.S. I expect there are venues that have done this work. Do you know of venues that have done the engineering to certify a measurable level of safe air on their premises? If so, please share in the comments! We should know about these conscientious organizations.

Shockingly, many in-person meetings now taking place require no pretesting of staff or attendees. (News flash: Checking someone’s forehead temperature when they enter a venue will not detect anyone who is infectious for the two days before symptoms appear, or who is asymptomatic.)

Even if everyone in the venue is tested daily, the widely used quick tests are simply too unreliable. From Nature again:

“Deeks says that a December trial at the University of Birmingham is an example of how rapid tests can miss infections. More than 7,000 symptom-free students there took an Innova test; only 2 tested positive. But when the university researchers rechecked 10% of the negative samples using PCR, they found another 6 infected students. Scaling that up across all the samples, the test probably missed 60 infected students.”

—Nature, February 9, 2021, Rapid coronavirus tests: a guide for the perplexed

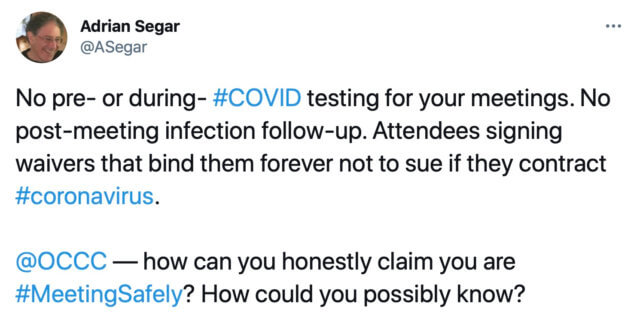

Finally, I find it upsetting that venues like the OCCC keep claiming that they are #MeetingSafely when they are doing no post-event follow-up! If an attendee contracts COVID-19 at the event, returns home and infects grandma, how would the OCCC ever know?! Under the circumstances, I think it’s misleading, dangerous, and unethical for such a venue to publicly claim that they are providing an #MeetingSafely environment.

In fact, some in-person meetings quietly acknowledge that they may not be providing a “safe” environment. One meeting venue held an in-person meeting that required waivers that forever bind attendees and their family members, and “heirs, assigns and personal representatives” not to sue if they contract COVID-19.

“I voluntarily assume full responsibility for any risks of loss or personal injury, including serious illness, injury or death, that may be sustained by me or by others who come into contact with me, as a result of my presence in the Facilities, whether caused by the negligence of the AKC or OCCC or otherwise … I UNDERSTAND THIS IS A RELEASE OF LIABILITY AND AGREE THAT IT IS VALID FOREVER. It is my express intent that this Waiver binds; (i) the members of my family and spouse, if I am alive, and (ii) my heirs, assigns and personal representatives, if I am deceased.”

—Extract from the Orlando, Florida, OCCC American Kennel Club National Championship Dog Show, December 2020, Waiver

I’m not sure how you can bind people to a contract who may not know they are a party to it. But, hey, I’m not a lawyer…

For the reasons shared above, I don’t believe we can safely and ethically hold in-person meetings right now. Consequently, it’s alarming that many venues, and some meeting planners, are promoting in-person meetings in the near future.

By now it should be clear that I stand with meeting professionals like Cathi Lundgren, who posted the following in our Facebook group discussions:

“I’m not going to be silent when someone holds a meeting in a ballroom with a 100+ people and no masking or social distancing…I own a global meetings company—and we haven’t worked since March but no matter how much I want to get back at it I’m not going to condone behaviors that are not positive for the overall health of our industry.”

—Cathi Lundgren, CMP, CAE

And here’s how I replied to the first Facebook commenter quoted at the top of this post:

“For goodness sake. I LOVE in-person events. It’s been heartbreaking for me, like everyone, to have not attended one for a year now. But that doesn’t mean I am going to risk stakeholder, staff, and attendee lives by uncritically supporting in-person meetings that are, sadly, according to current science, still dangerous to attend. When in-person meetings are safe to attend once more — and that day can’t come soon enough — you bet I’ll be designing, facilitating, and attending them.”

I hope it’s clear that I, and those meeting professionals who are pointing out valid safety and ethical concerns, don’t hate in-person meetings. Realistically, the future of in-person meetings remains uncertain, even with the amazing progress in developing and administering effective vaccines. More mutant COVID-19 strains that are resistant to or evade current vaccines, transmit more effectively, or have more deadly effects are possible. Any such developments could delay or fundamentally change our current hopes that maintaining transmission prevention plus mass vaccination will bring the pandemic under control.

I’m cautiously optimistic. But, right now, there are still too many unknowns for me to recommend clients to commit resources to future large 100% in-person events. Hub-and-spoke format hybrid meetings look like a safer bet. Regardless, everyone in the meeting industry hopes that it will be safe to hold in-person meetings real soon.

In the meantime, please don’t attack those of us in the industry who point out safety and ethical issues and the consequences of prematurely scheduling in-person meetings. We want them back too! We all miss them.

In order to overcome the many significant challenges created by the coronavirus, the meeting industry has made valiant efforts to rethink in-person meetings. The goal? To bring people safely into the same physical space, so they can meet as they did before the pandemic.

Sadly, I believe such efforts are based on wishful thinking.

It’s nice to imagine that, if we can figure out how to bring people safely together in person in a COVID-19 world, our meetings will be the same as they were pre-pandemic.

But until we create and broadly administer an effective vaccine (or we suffer the disastrous and massive illnesses and deaths that will occur obtaining herd immunity) they can’t be the same meetings.

Moreover, there are two reasons why there is no persuasive use case for holding almost any in-person meetings in a COVID-19 world.

By now we know that in order to reduce the spread of COVID-19, people near each other must:

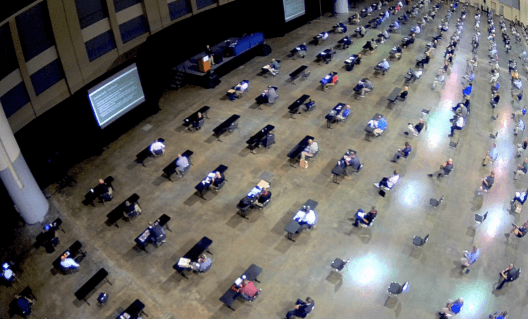

Here’s what that looks like at an in-person meeting.

Let’s set aside the significant issues of whether attendees can:

While difficult, I think we can do all these things. Well-meaning meeting industry professionals are understandingly desperate to bring back in-person meetings from oblivion. But they assume that if they can solve the above challenges, an effective meeting can occur.

In doing so, they have reverted to the old, deeply embedded notion that, fundamentally, in-person meetings are about listening to broadcast content. Since the rise of online, broadcast-format content can be delivered far more inexpensively, efficiently, and conveniently online than at in-person events.

As I have explained repeatedly in my books and on this blog (e.g., here) assuming that conferences are fundamentally about lectures ignores what is truly useful about good meetings.

Among other things, good meetings must provide personal and useful connection around relevant content.

Unfortunately, you cannot connect well with people wearing face masks who are six or more feet away!

In addition, new online social platforms (two examples) provide easy-to-learn and fluid video chat alternatives to the in-person breaks, meals, and socials that are so important at in-person meetings. Do these tools supply as good connection and engagement as pre-pandemic, in person meetings? Not quite. (Though they supply some useful advantages over in-person meetings, they can’t replace friendly hugs!) Are they good enough? In my judgment, yes! In the last few months, I’ve built and strengthened as many relationships at online meetings as I used to in-person.

Right now, the learning, connection, and engagement possible at well-designed online meetings is at least comparable — and in some ways superior — to what’s feasible at in-person meetings that are safe to attend in a COVID-19 world.

Now add the significant barriers and costs to holding in-person meetings during this pandemic. The challenges of providing safe travel, accommodations, venue traffic patterns, and food & beverage all have to be overcome. Even if credible solutions are developed (as I believe they can be in many cases), potential attendees must still be persuaded that the solutions are safe, and your meeting can be trusted to implement them perfectly.

I’ll share my own example, as a 68-year-old who, pre-pandemic, facilitated and participated in around fifty meetings each year. Since COVID-19 awareness reached the U.S. five months ago, I have barely been inside a building besides my home. I have only attended one in-person meeting during this time: a local school board meeting held in a large gymnasium with the fifteen or so masked attendees arranged in a large circle of chairs in the center of the room. I am not willing to fly anywhere, except in the case of an emergency. Everyone has their own assessment of risks taken during these times. But I will simply not risk my health to attend an in-person meeting at present. Especially when online meetings provide a reasonable substitute. I don’t think I’m alone in this determination.

I do not think that the research initiated and venue upgrades made are a waste of time, money, and effort. There may well be a time when an effective vaccine exists and is being introduced. At this point, in-person meetings may be able to start up again without the critical barriers introduced by universal masks and social distancing.

Until then, I don’t see a credible use case for holding significant in-person meetings in a COVID-19 world.

Image attribution: Erin Schaff/New York Times