Meeting room designs for both in-person and remote participants

Now that small hybrid meetings are commonplace, what meeting room designs work for a mixture of in-person and remote participants?

Read the rest of this entry »

Now that small hybrid meetings are commonplace, what meeting room designs work for a mixture of in-person and remote participants?

Read the rest of this entry »

The words we use for meetings matter. Unfortunately, familiar terms often perpetuate conventional meeting thinking. By changing the words we use, we can change how we think about events. Here are three examples of better words to use when talking about meetings.

The words we use for meetings matter. Unfortunately, familiar terms often perpetuate conventional meeting thinking. By changing the words we use, we can change how we think about events. Here are three examples of better words to use when talking about meetings.

When the COVID-19 pandemic began, in-person meetings vanished overnight. Suddenly Zoom became a household word. If we couldn’t safely meet face-to-face, we’d sit in front of screens.

But what should we call these internet-mediated meetings?

In July 2020, I suggested that we not call them virtual meetings. Instead, I made the case to use the word online. In essence, I pointed out that virtual has the connotations of “not quite as good” and unreal, while online is a neutral and well-established description of the meeting medium. Read the post for a detailed argument.

Though I don’t claim any credit, I’m happy to observe that meeting industry professionals and trade journals currently tend to prefer “online meeting” to “virtual meeting,” though there are some notable exceptions. Google also shows the same preference, with 5.0B search results for “online meeting” versus 1.3B for “virtual meeting.”

This is a big one and a harder switch to make. The word networking has been used so often to describe what people do at meetings that it’s tough to supplant. But describing everything that happens outside event sessions as networking subtly directs attention away from what can be the most valuable outcome of well-designed meetings: connecting with others.

We’ve biased how we talk about connection at meetings by using a word that is much more focused on personal and organizational advantage than personal and professional mutual benefits.

I lightheartedly titled my recent post on this topic, “Stop networking at meetings“. But it’s a serious suggestion. Having a mindset of encouraging and supporting connection around useful content plus a set of meeting process tools that can make it happen is a game-changer for meeting effectiveness.

Sadly, I’m a voice in the wilderness on this one. 13 years ago, I wrote Why I don’t like unconferences. As I explained in my first book, Conferences That Work, what people call an unconference is what a good conference should actually be. At unconferences, far more conferring goes on than at traditional events. I coined the term peer conference as an attempt to remove the “un” from “unconference”.

I was ignored.

This linguistic problem worsened as people decided that calling traditional events “unconferences” made them sound cool. They ignored the central feature of an unconference; that sessions are chosen at the event rather than scheduled in advance. These days I frequently see advance calls for speaker submissions at meetings advertised as “unconferences”! You even find traditional breakout sessions described as unconferences, presumably because more than one person might speak. I cover these depressing developments in These aren’t the unconferences you’re looking for.

Today, “peer conferencing” is principally used to describe an educational approach to writing in groups. So I’ve reluctantly given up trying to swim against the tide and have been using the term unconference in my recent writing.

C’est la vie.

The words we use for meetings matter. My little campaigns to reframe some language the meeting industry uses have had mixed results. What do you think of my suggestions? Are there other examples of meeting industry language you’d like to see changed? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Apropos of nothing, here, in alphabetical order, are some meeting industry terms I like. Don’t ask me why.

[Note: This event was a workshop, not a presentation. Sessions are often advertised as “workshops” that aren’t. If you want to know the difference, read this.]

I think my biggest regret about this workshop is that it felt rushed. Why? The quick answer is that I tried to include too much for the time available. But it’s more complicated than that.

Don Presant asked me to offer a CSAE session of up to an hour in length. I asked for the maximum. In retrospect, I should have asked for more time. (I might not have got it, but it never hurts to ask.) After the workshop, Don asked me how much time I would have preferred. “Two hours,” I replied immediately.

Over the years I’ve become good at keeping to the time allocated for sessions. My approach is simple; I practice what I plan to do with a stopwatch running and keep paring down what I’d thought to include until it fits. I note the elapsed time at the start of each new segment and check how I’m doing during the session, adjusting accordingly.

This workshop didn’t work out so well. I cover the logistical reasons below. But being rushed is never good. I had never tried to run a one-hour online workshop before. And one lesson I learned is that I’m not going to try to run one in just one hour again.

My workshop was designed to include two chunks of content and two participative exercises. As is usually the case in my workshops, I work at two levels. I try to make the workshop personally useful for the participants by allowing them to learn about each other. Simultaneously, participants experience and get familiar with how the formats I use work.

This workshop would have been better in person. I probably could have done it in an hour. What made it rushed online was the time taken to switch between content and participative segments, and the toll this took on the flow of the session.

If I’d run this workshop in person, I could have easily run it by myself. Online, I needed two assistants — thank you, Don and Carrie Fischer! Don did the intro and close, monitored the chat, and fed me questions. Carrie hosted the meeting on Zoom, set up multiple breakout rooms, and messaged instructions while the breakouts were in session. There’s no way I could have run this workshop without them. Yet I now realize that having one of them or a third person manage the context switches between the interactive and content portions of the workshop would have helped me a lot!

Over the last couple of years, I’ve run multiple successful two-hour or longer online workshops. Looking back at the run of shows, these workshops had a similar or fewer number of context switches between interactive and content segments. Consequently, I’m going to allocate longer time for workshops than an hour from now on.

One unexpected logistical concern occurred just before the workshop started. Instead of using CSAE’s Professional Zoom account, we had to use mine. Fortunately, my Zoom settings were set as I needed them to be, but I did worry that this would require me to take over some of Carrie’s work. Luckily, with Don and her as co-hosts, Carrie was able to handle the usual Zoom support.

Unfortunately, I was responsible for the context switches between Zoom Gallery mode and sharing my keynote presentation slides. That was a mistake; at least the way I tried to implement it.

There are several ways to share a Keynote presentation in Zoom. My favorite is to share my Keynote presentation as a virtual background in Zoom. Zoom has described this functionality as “beta” for a while, but I’ve not had any problem with it to date except for the minor bug I found this time, as described below. My “talking head” is superimposed on my slide at the size and position I choose. Here’s an example (this is my view as the presenter):

This works well for a one-off presentation in a Zoom meeting. However, it turns out to be painful to implement when you need to switch in and out of Keynote during a workshop. Here’s why:

During the hour workshop, I had to perform six context switches while facilitating: Gallery->Keynote->Gallery->Keynote->Gallery->Keynote->Gallery. I found it distracted my mental flow, especially the several steps involved in starting up a different Keynote deck each time.

In Gallery View, I used breakout rooms and a camera off/on technique for simple human spectrograms and fishbowl discussion during the last segment of the workshop. This was complicated to manage in the short time available, and I felt the quality of the workshop suffered.

I mentioned these problems to my friend and event production expert Brandt Krueger, who sympathized. He pointed out that I had encountered limitations of software-based solutions to what are essentially production issues. For example, I could run Keynote on a second machine (I have three in my office) and use a switcher to instantly switch video between the Zoom and presentation computers. (Brandt loves the ATEM Mini switcher, and I have come close to buying one on several occasions.)

I had assumed that what I’d rehearsed might take a little longer when I went live. And I expected to spend some time answering impromptu questions during the first three segments of the workshop. But I had reserved what I thought was enough time for the open-ended final discussion so I could still end on schedule.

As it turned out, I underestimated the slowdown from context switching. Answering a couple of questions brought me to the final segment about ten minutes later than I had planned. The time for the concluding discussion was shorter than I would have liked. We went over a few minutes, and I cut a final “lessons learned” pair share I had planned to include.

Although I covered everything I’d planned, the workshop felt rushed to me, and I don’t do my best work under the circumstances.

Well, that’s how you learn. I’ll do better (and allow longer to do it) next time.

There are some of the lessons I learned from this online workshop. I hope they help you avoid my mistakes. If you have other suggestions for improving the challenging exercise of running an ambitious online workshop, please share them in the comments below.

Registration is limited, so register now!

Online on Wednesday, May 11, 2022 — 12:00 – 1:00 pm PDT • 1:00 – 2:00 pm MDT • 2:00 – 3:00 pm CDT • 3:00 – 4:00 pm EDT • 8:00 – 9:00 pm BST • 9:00 – 10:00 pm CEST.

We’ve known for a long time that lectures are terrible ways to learn. Today’s attendees are no longer satisfied sitting and listening to people talking at them. If you want to hold meetings where effective learning, connection, and engagement take place, you need to build in authentic and relevant participation.

Our time together at this Participate Lab will cover:

This workshop is limited to 100 attendees, so register now!

The first novel hybrid meeting format was invented by Joel Backon back in 2010. The second is a design I’ll be using in a conference I’ve designed and will be facilitating in June 2022.

Back when hardly anyone used the term “hybrid” for a meeting, let alone participated in one, I had the good fortune to participate in a novel session “Web 2.0 Collaborative Tools Workshop” designed by Joel Backon at the 2010 annual edACCESS conference. During the session, all the in-person participants had an online experience, followed by an in-person retrospective. The online portion felt eerie…

“Some participants had traveled thousands of miles to edACCESS 2010, and now here we were, sitting in a theater auditorium, silently working at our computers.”

—Adrian Segar, Innovative participatory conference session: a case study using online tools, June 27, 2010.

Check out my original post for the details of the session, which explored the unexpected advantages of working together online even when the participants are physically present. The experience certainly opened my eyes to the power of collaboratively working on a time-limited project using online tools.

You can use this novel hybrid meeting format to explore the effectiveness of employing appropriate online tools to work on problems at an in-person event. Following up the exercise with an immediate in-person retrospective uncovers and reinforces participants’ learning.

These days it’s even easier to implement similar hybrid sessions at in-person meetings. Participants will learn a lot while exploring the advantages and disadvantages of collaborating online!

As I write this I’m designing a one-day, in-person peer conference for 150 members of a regional association. As readers of my books know, running a peer conference for this many people in one day would be a somewhat rushed affair. Unfortunately, the association practitioners simply couldn’t take off more than a day to travel to and attend the event.

Squeezing The Three Questions, session topic crowdsourcing, the peer sessions themselves, and at least one community building closing session into a single day is tough. In addition, the time pressure to quickly crowdsource good sessions and find appropriate leadership is stressful for the small group responsible for this important component.

To relieve this pressure I’ve designed a hybrid event that once again uses the same participants for both the online and in-person portions.

The day before the in-person meeting, participants will go online briefly twice, in the morning and in the afternoon. During the morning three-hour time slot, participants can suggest topics for the in-person conference. We’ll likely use a simple Google Doc for this. They will be able to see everyone’s suggestions and can offer to lead or facilitate them.

Around lunchtime, a small group of subject matter experts will clean up the topics. Then, during the afternoon three-hour time slot, participants will vote on the topics they’d like to see as sessions the following day. The evening before the conference, the small group will convene and turn the results into a tracked conference program schedule that reflects participant wants and needs. They will also decide on leadership for each session. (Read my book Event Crowdsourcing to learn in detail how to do these tasks.)

Moving the program creation online the day before the in-person event allows participants to spend more time together in person. This choice sacrifices the rich interactions that occur between participants during The Three Questions. But in my judgment, the value of creating a less rushed event in the bounded space of a single day is worth it.

[Want to read my other posts on hybrid meetings? You’ll find them here.]

I believe we’ve barely started to explore the capabilities of hybrid meeting designs. Including both online and in-person formats in a single “event” multiplies the possibilities in time and space. I’m excited to see what new formats will appear in the future!

Have you experienced other novel hybrid meeting formats? Share them in the comments below!

Here’s a rare opportunity to ask me anything about meeting design and facilitation at a unique, free, online workshop. Join me next Thursday, March 10th, 2022 at 12:00 pm EST for Ask Adrian Anything (AAA): an online participant-driven workshop on the future of events.

Though the central core is the AAA session, this is an active learning workshop. During it, you’ll experience some of the practices I use to support and build participant learning, connection, engagement, and community.

How long will the workshop last? That’s up to you! I’m willing to keep it going as long as you have questions and concerns to share. When it’s over, you’re welcome to stay and socialize online, and I’ll stick around for informal chats.

If you want to join us, it’s important you’re ready to begin at 12:00 pm EST. We’ll open the workshop platform at 11:45 am EST so you’ll have time to do the usual camera/microphone online setup boogie for a prompt start at noon EST.

This is an opportunity for you to experience one of my participant-driven workshops. You’ll learn through doing, both about other participants and how to implement what you experience into your own events.

And, like Colin Smith, the protagonist (played by Tom Courtney) of the classic 1962 film The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner, I sometimes feel alone.

Meeting via Zoom is far better than not meeting at all, but it doesn’t compare with being with people face-to-face.

I love to facilitate in-person meetings, and I miss the personal connection possible there.

But even when I facilitate in-person meetings, there are times I feel lonely. No, not while I’m working! Not when I work with clients to design great meetings, create safety, uncover participants’ wants and needs, moderate panels, crowdsource conference programs and sessions, facilitate group problem-solving, and run community-building closing sessions.

But there are times during the event when I’m not working. While the sessions I helped participants create are taking place. During breaks when I’m not busy preparing for what’s to come. And during socials.

At these times, I feel a bit like The Invisible Man.

Why? Because, though I may have facilitated and, hopefully, strengthened the learning, connection, and community of participants present, I’m not a member of the community.

In the breaks and socials, I see participants in earnest conversations, making connections, and fulfilling their wants and needs in real-time. But I’m hardly ever a player in the field or issues that have brought them together. (Usually, as far as the subject matter of the meeting is concerned, I’m the most ignorant person present.) So I don’t have anyone to talk to at the content level. I’m physically present, but I don’t share the commonality that brought the group together. It’s about participants’ connection and community, not mine.

I may have made what’s happening better through design and facilitation, but it’s not about me.

Every once in a while, participants notice me and thank me for what I did. It doesn’t happen very often—and that’s OK. My job is to make the event the best possible experience for everyone. My reward is seeing the effects of my design and facilitation on participants. If I were doing this work for fame or glory, I would have quit it long ago.

If you’re at a meeting break or social and see a guy wandering around who you dimly remember was up on stage or at the front of the room getting you to do stuff?

It’s probably me.

Paradoxically, when I facilitate online meetings there’s no “invisible man” lonely time. Whenever we aren’t online, we’re all alone at our separate computers. We can do whatever we please. We were never physically together, so we don’t miss a physical connection when we leave.

The loneliness of the long-distance facilitator is accentuated at in-person events by the abrupt switches between working intimately with a group and one’s outsider status when the work stops.

At online events, we are all somewhat lonely because no one else is physically present. Our experiences of other people are imperfect instantiations: moving images that sometimes talk and (perhaps?) listen.

It wouldn’t be a no-brainer choice, but if I had to choose between facilitating only in-person or online meetings, I’d choose the former. The intimacy of being physically together with others is worth the loneliness when we’re apart.

Image from The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner

The most popular of the in-person sessions I design and facilitate is The Solution Room (here are some testimonials). The 90 – 120 minute session, for 20 – 600 people, engages and connects participants, and provides just-in-time peer support and answers to their most pressing professional challenges. These days, wouldn’t it be great to run The Solution Room online? Well, you can!

I’ve described in detail how to run The Solution Room at in-person meetings in my last two books: The Power of Participation & Event Crowdsourcing. The latter has the most up-to-date instructions, but either book should suffice. (Don’t have a copy? For the price of a sandwich you can buy either ebook.) So this post covers just the changes you’ll need to make to hold this highly-rated plenary session on an online/virtual platform.

To run The Solution Room online you’ll need:

The Solution Room facilitator follows the “How?” section of the relevant chapter in The Power of Participation (Chapter 34) or Event Crowdsourcing (Chapter 23) with the following modifications.

In advance of the session, ask participants to have available a method of creating a drawing to share with their small group. Provide detailed options, so they know how they’re going to create their drawing and how they’ll share it.

Before starting, have your staff check that every participant is displaying their name in the participant list.

Introduce The Solution Room, and provide the link to the shared Google Sheet years-of-experience sheet (here’s my sample Sheet). Ask participants to think of their challenge, and then enter their Zoom name in the column headed by their number of years of experience.

Once everyone has entered their years of experience, your staff can calculate the number of breakout rooms needed. While you continue, staff pre-assigns participants to breakout room tables using the information in the Google Sheet.

The sample Google Sheet contains twenty participants. So if we are using a table size of seven, we will need three breakout rooms. Your staff will, therefore, go through the Sheet from the left, down each column, and then to the right, assigning each participant a number between 1 and 3. For the example, the three tables will be:

#1: Julio Melia, Marvin Brentwood, Elizabeth Strong, Gurdeep Mac, Liliana Hoffman, Ivor Rennie, Zahrah Valenzuela

#2: Harold Kormann, Fergus Roth, Khi Suliman, Bayley Sims, Arian Faulkner, Alayah Hurley, Adrian Segar, Tyriq Kenny

#3: John Smith, Mario Fernandez, Selina Hatherton, Malaika Byers, Inigo Tyler

Each table contains a mixture of years of experience, from novice to veteran.

Run the comfort spectrogram, sharing your campfire and jungle images at the appropriate times. If you have a polling instrument, ask each participant to rate their pre-exercise comfort level on working on their challenge on a scale of 1 (extremely uncomfortable) to 10 (perfectly comfortable) and to enter their rating. No polling instrument? Simply ask them to remember their rating.

While everyone is still together, give the mindmapping instructions and give participants a few minutes to create their drawings. Ask participants to turn off their cameras, raise their hands, or provide some other signal that they have finished. Tell them they can use private chat with the facilitator or staff if they have any questions.

When it’s time for table sharing to start, provide the instructions for table sharing. Answer any questions, and then move participants to their breakout room tables, or tell them their table number and have them move there.

Use broadcast messages to provide the midway, two-minute, and time’s up announcements. At the start of the last sharing round, remind tables with one empty seat to use the time for additional consulting.

Ask everyone to thank their table colleagues for their advice and support. Allow a couple of minutes for this, and then bring everyone back together.

Display the jungle and campfire images and run the second comfort spectrogram. If using a polling instrument, compare the pre- and post- comfort distributions. Otherwise, you can ask people to raise their hand for three options in turn: their comfort level increased, stayed the same, or decreased.

If desired, run the likelihood that participants will work to overcome the challenge they just shared.

Finally, if you have time and the inclination, take some sharing about the exercise, using an appropriate “who goes next” protocol.

That’s it! If you run The Solution Room online, please feel free to share your experience in the comments below.

My goals? To give people an opportunity to reminisce, share how they feel, catch up with old friends and make new ones, perhaps obtain some measure of closure, and have some fun.

We can currently only hold such gatherings online. So I’m sharing my design here, in the hope it’s helpful to others.

Given the above objectives, I worked on a design loosely based on what happens at traditional, in-person memorial services. Typically, these start with a formal set of remembrances and end with a social.

Most people have never attended an online memorial service before. So it’s important to give them an idea of what to expect. Besides explaining the program, as outlined below, we need to set expectations about what will happen during the event.

In this case, whether the school actually needed to close, how that decision was made, and the eventual closing of the school were all contentious issues. They stirred up a lot of feelings in the wider community. Orating about these (totally valid) feelings during the event would be like publicly complaining at a funeral about the poor quality of medical care the deceased received, or attacking other family members for caring poorly for the deceased. I decided that our event would not include public denigration, and included a statement to this effect in the invitations.

I also chose to call the service a “wake”, rather than a “memorial” or “funeral” for the school. Some participants who have not been actively involved with the school for decades may see the event principally as a way to share pleasant memories and catch up with old friends. The term wake evokes a more informal event and experience than that of a traditional funeral. I decided to start somewhat formally with everyone together, as in a traditional memorial service. Normally, such events transition into an in-person social, typically with food and drink available.

Many in-person memorial services allow people to “come up to the microphone” when the spirit moves them. This doesn’t work so well online with a large group. There may be frequent pauses and it’s hard to create a workable presumption as to how long people speak.

So right now, I’m assuming that we will have a prescheduled opening program. During registration, we’re asking those who want to share to give us an idea of what they might do or say. Each contributor will know in advance when it’s their turn to share, and how long they have “on mike”.

Depending on the number of people who indicate they want to speak, we may include some time at the end of the opening program for a few additional people to share.

Because this service is online, I’ve decided to add an optional transition between the formal remembrances and the ending social. To help reconnect people who have spent time together in the past, we’ll provide online “rooms” for specific groups. As the registrations come in, I will use the affiliation information included to create appropriate descriptions for these rooms. For example, we might have rooms for alumni who graduated in the 60’s or between ’90 and ’95, a room for staff, and a room for faculty. Registrants will preselect a room they’d like to join, and go there at the end of the formal session.

A year ago, there were few good options for providing an online substitute for an in-person social. Luckily, a host of new platforms have appeared this year (1) (2) that offer a great online social experience. I’ll have one of these available during the second and third phases of the service.

I decided to design the wake as a three or more hour event. It’s scheduled to be optimum for North American participants (6:00 — 9:00+ pm EDT). This timing is not great for potential European attendees. But I reluctantly felt it necessary to focus on the majority of the target audience.

We’ll use two online platforms for the wake. I will run the opening, with everyone together, in Zoom, and use Zoom breakout rooms for the following smaller group get-togethers. The online social will be available after the opening, and will use one of the platforms mentioned in the above reviews.

Attendees (~90 right now) are registering on an online platform that’s free for free events. During registration, people let us know if they’d like to share something brief with everyone at the start, and, if so, what it would be. They can also suggest ideas for activities at the event, plus offer to help with any of the logistics:

I am closing registrations five days before the event. This gives me and my volunteer assistants time to fine-tune the program, and figure out the amount of logistical support we’ll need.

One thing I’ve found invaluable in running large online meetings is a private channel for the event staff to communicate beforehand and in real-time during the event. (Meeting planners have employed wireless technology solutions to do this for decades.) I like to use a private Slack channel for this. Basic Slack has a short learning curve, has clients for every platform, and a free account is all you need.

I hope this post will help you with designing an online memorial service. Have you designed and/or run one? What did you learn? What would you like to share to make the above advice more useful? Please let us know in the comments below!

How can we create great online breakout sessions?

You attend a conference session on a topic that interests you. Perhaps you’re a novice, an expert, or someone in between. Or perhaps you want a general introduction. Perhaps you have a few specific issues you want to hear about or questions to which you’d love to get answers.

The presenter begins, and you quickly realize the session is not going to meet your needs. (Or, even worse, you sit through the whole thing, expecting your specific interests to be addressed — but they never are.)

How many other attendees are having the same experience? How many attendees are getting their wants and needs met by this session?

We will probably never know.

At traditional sessions, you might get a hint of how well the presenter met wants and needs at the end, when “there’s time for a few questions”. Whatever you discover at that point, it’s too late.

There’s a better approach.

Whether a breakout session is in-person or online, the way for a leader or presenter to make it great is to:

This approach works because it makes a transparent effort to provide an optimal session for the participants: what they actually want and need. Participants appreciate this! You might end up with a plan like this one:

“It looks like about a third of you are relatively new to [the session topic] and you’re mainly interested in an introduction. The rest of you seem most interested in spending time learning about X & Y. A couple of you have specific questions that I can answer quite quickly.

I can provide an introduction to [the session topic]. Ayesha has expertise in X, and Cyrus and I know about Y. I propose I start with an introduction to [the session topic] for ten to fifteen minutes. Then let’s turn the session over to Ayesha for fifteen minutes on X, followed by Cyrus & me for around fifteen minutes on Y. During the remainder of the session I’ll answer the two specific questions, and we’ll use any remaining time to answer final questions.

How does that sound to everyone?”

The transparency of this process is really important, because, of course, it’s impossible to create a session that’s perfect for everyone. Suppose, for example, that you have a specific need that might take up most of the session to be fulfilled…and you’re the only person who asks for this. OK, so you’re not going to get your needs met, but at least you understand why. Furthermore, a smart presenter may still be able to offer an opportunity to respond to your need: e.g., “John, we don’t have time in this session to talk about Z, but email me and I’ll send you some articles that should be helpful.”

At in-person events, it’s easy to uncover audience interests using the Post It! For Sessions technique described in Chapter 26 of my book Event Crowdsourcing. The presenter supplies a pen and sticky note to each attendee and asks them to write down one topic they would like explored, or a question they would like answered during the session. The notes are collected and categorized into broad themes, and the presenter designs a responsive session, like the one above, on the spot. (Check out the book for more details.)

With a little ingenuity, it’s simple to modify Post It! For Sessions for an online breakout session.

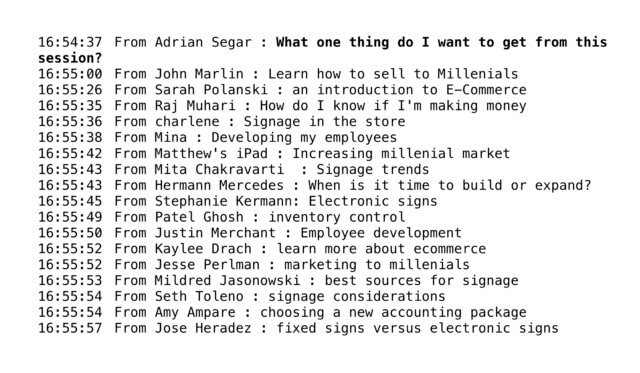

To start, ask everyone to come up with their answer to this question:

“What one thing do I want to get from this session?”

Tell them that their response can be specific or general; they get to choose what they most desire. Give them a minute to think about their answer, and ask them to post it in the online platform’s text chat.

Now, you and your participants have a much better idea of the wants and needs in the “room.”

Quickly review the requests, and ask submitters to clarify any that are unclear or vague.

Then create a brief plan for the session, based on the expressed wants and needs. Don’t feel obliged to cover everything mentioned. Describe your plan briefly, and apologize for topics you won’t be able to cover in the time available. Ask if there are subject matter experts in the room that can address some of the topics raised, and incorporate that information into your plan. Ask for feedback and adjust the plan if necessary.

Then do it!

You can create great online breakout sessions in about five minutes. Taking the time to discover what participants want and need and creating a session that meets the group’s desires as closely as possible will pay rich dividends. Try it and see!