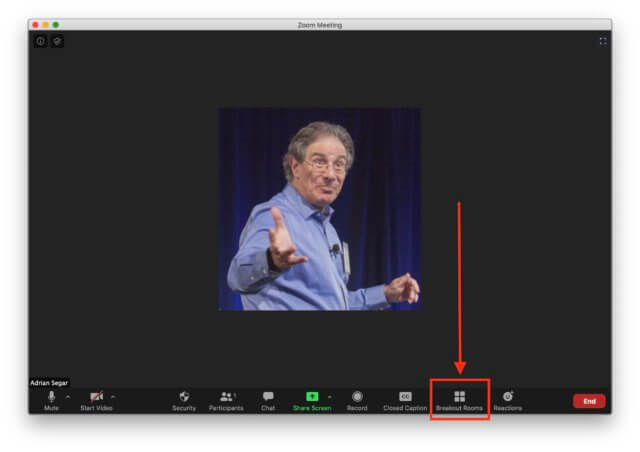

How to implement participant-driven breakouts in Zoom

I’ve been designing and facilitating participant-driven and participation-rich in-person meetings — aka peer conferences — for almost thirty years. Why? Because participants love these meetings!

Now the COVID-19 pandemic has forced meetings online. Unfortunately, most online events are still using a traditional webinar/broadcast-style approach: presenters speaking for long periods, interspersed with chat-mediated Q&A.

Why Zoom?

Zoom has rapidly become the dominant platform for online meetings. Though there are many features that would make the platform better, it’s popular for good reason. Zoom:

- has a well-chosen feature set;

- is relatively easy to use; and

- has proved very reliable despite the platform’s meteoric growth.

While Zoom is currently missing some functionality that would smooth the process flow, it’s already a viable platform for online peer conferences.

I started using Zoom in 2012, but since the pandemic began I’ve facilitated more Zoom meetings than the last seven years. And I’ve become intrigued with the possibilities of incorporating the peer processes developed for successful face-to-face meetings into online events.

I’ve written three books about why creating participation-rich conferences that deliver effective learning, connection, engagement, and action is so important, and how to do it for in-person events. So I won’t repeat myself here; read them for full details!

In-person meetings have vanished overnight. It’s time to implement what we’ve learned about great face-to-face meeting design and process into online meetings. Meetings will never be the same. When the pandemic is over, the meeting industry will have much more experience and understanding of what is possible online versus in person.

My mission is to make meetings better for everyone involved. That’s why I’m publishing this series of posts on how to implement participant-driven breakouts in Zoom.

I’ll start with an overview.

The big picture

The core reason why peer conferences work is that they become what participants actually want and need. They accomplish this in real-time — during the event — via two essential steps:

- At the start of the conference, uncover participants’ wants and needs and the resources in the room.

- Develop an optimum conference program that matches the uncovered wants and needs with the resources in the room.

Once the conference program has been developed and scheduled, you’re ready to hold the resulting peer sessions. I’ll explain how to do this in a future post.

Step #1

I’ve been implementing step #1 at in-person events for twenty-five years, using a process called The Three Questions, which is described in detail in my book Event Crowdsourcing: Creating Meetings People Actually Want and Need. In Part 2 of this post, I’ll explain how to implement The Three Questions using Zoom breakout rooms.

As in face-to-face events, I recommend allocating at least ninety minutes for step #1. If you are running an extended event (see below) with multiple sets of breakout sessions, schedule two hours. Note that these times include short breaks, as described in this post.

At the end of step #1:

- Participants will have met a useful number of other participants and learned useful information about each other, namely, details of their association with the meeting topic, their wants and needs for the meeting, and their relevant expertise and experience.

- Conference organizers will have a comprehensive list of topics, issues, and challenges that are top-of-mind for attendees, plus identified participants who can facilitate/lead/present on them.

Step #2

Step #1 generates a large amount of information about attendees’ real-time wants and needs, as well as relevant expertise and experience that can be tapped.

During step #2, conference leaders and subject matter experts use this information to create an optimum conference program. In Part 3 of this post, I’ll explain how to do this. What’s important to know is that step #2 takes time!

For a small meeting (e.g., 60 people, two one-hour time slots with three simultaneous sessions per slot ==> 6 peer sessions), creating the program might take 30 – 60 minutes.

For a larger event (e.g., 100 people, three one-hour time slots with five simultaneous sessions per slot ==> 15 peer sessions,) choosing a program might take 90 – 150 minutes.

Regardless of the time needed, conference attendees should be otherwise engaged during step #2.

You have (at least) three options at this point.

Allow attendees free time while the conference program is designed

One option is to schedule an attendee break that’s long enough to complete step #2. For example, if your attendees are from the same or contiguous time zones, consider scheduling step #1 so it ends around lunchtime for most of them. Your pre-conference schedule could then include an hour or more break for lunch while the program is developed.

Schedule a presentation for attendees during step #2

While conference leaders and subject matter experts are using step #1 information to choose and schedule peer sessions, the other participants attend a pre-scheduled presentation or session of some kind that’s long enough for step #1 to be completed.

Be sure to include at least a short break between the end of step #1 and the start of the presentation.

One minor drawback of this approach is that step #1 often involves checking the availability of participants who have relevant experience or expertise to lead a peer session, as well as their willingness to do so. Doing this (typically by private message in Zoom text chat) while these participants are involved in another session can be a little disruptive.

Schedule steps #1 and #2 on different days

A third option is to schedule your entire event over two or more days. This gives ample time for step #1 to be completed. For example, you could run step #1 for a couple of hours on Monday morning or afternoon, then complete step #2 and distribute the resulting conference program, and run the resulting peer sessions on Tuesday.

Conclusion

In this post, I’ve provided a brief recap of the benefits of peer conferences, and given a big-picture overview of how you can hold one online. Future posts will cover detailed descriptions of how to carry out steps #1 and #2 using Zoom.

Check back on this blog for upcoming posts on implementing participant-driven breakouts in Zoom. To ensure you don’t miss them, subscribe.

Should meetings be efficient?

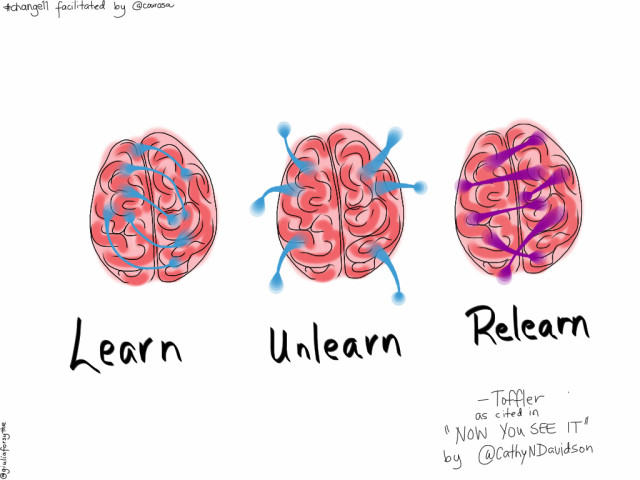

Should meetings be efficient? Unlearning is crucial for change.

Unlearning is crucial for change.

Legendary Apple designer

Legendary Apple designer  My Dutch friend and expert moderator,

My Dutch friend and expert moderator,  I often design and facilitate workshops for association members most of whom haven’t met before. The desired outcomes are for each participant to gain useful and relevant professional insights, and to make significant new connections.

I often design and facilitate workshops for association members most of whom haven’t met before. The desired outcomes are for each participant to gain useful and relevant professional insights, and to make significant new connections.