Why organizations fear connecting

Seth Godin points out that many organizations fear connecting because their leadership fears losing control. Even though the control they think they have is a myth.

“Organizations are afraid of connecting. They are afraid of losing control, of handing over power, of walking into a territory where they don’t always get to decide what’s going to happen next. When your customers like each other more than they like you, things can become challenging.

Of course, connecting is where the real emotions and change and impact happen.”

—Seth Godin, ‘Connect to’ vs. ‘Connect’

The importance of connection

A survey I conducted of attendees while writing Conferences That Work confirmed (as do many other meeting surveys) that the two most important reasons people go to meetings are to connect (80%) and learn (75%).

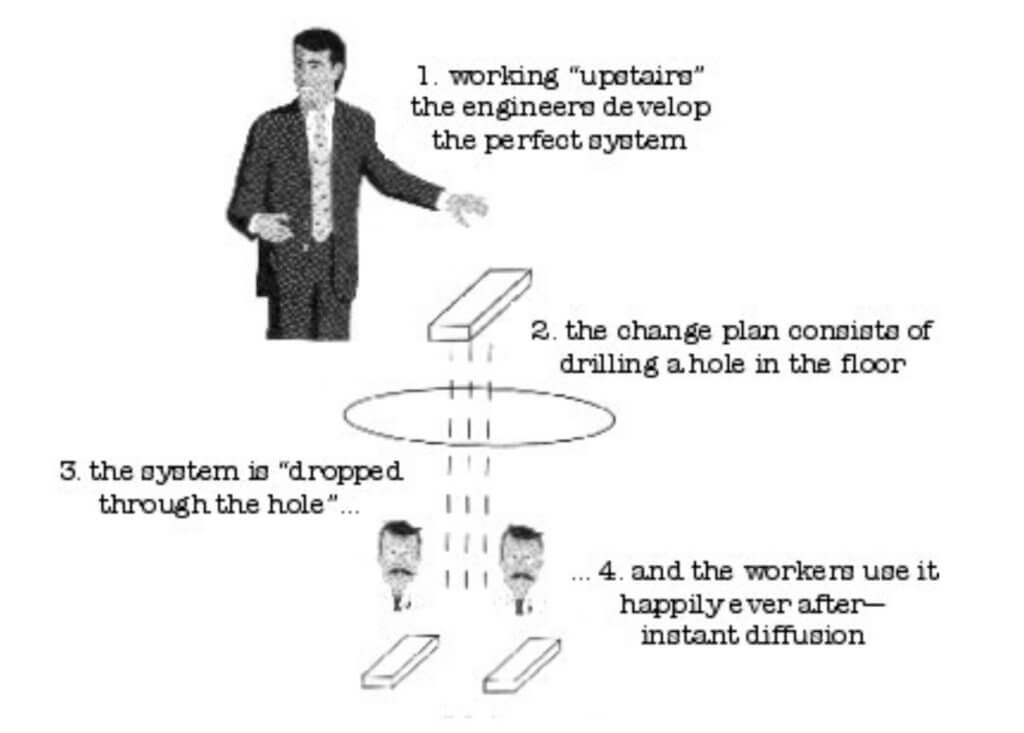

Nevertheless, many conferences are structured like this.

No one’s connecting here, except, maybe, a single speaker to his audience. The audience members aren’t connecting with each other at all.

To create connection, conferences need to be structured like this.

Here, we see people gathered together, talking, listening, and taking notes. Active learning, rather than passive reception of lecturing, is the model. Active learning is a better model for meetings because it builds connection around meaningful learning.

An organization that fears connecting:

- Employs hierarchical meetings and events, controlling what happens by using a predetermined agenda of broadcast-style lecture sessions.

- Creates a fundamental disconnect between the wants and needs of the staff and/or members and the structure of its meetings and conferences. Events that provide connection-rich sessions, allowing participants to discover their tribe and determine what they discuss, are anathema.

“Connect to” is a goal; “connect” is a verb

Seth again:

“An organization might seek to ‘connect to’ its customers or constituents…That’s different, though, than ‘connect'”

Some organizations try to obscure their control-based culture by asserting their goal is to “connect to/with” their clients. There’s plenty of plausible-seeming advice available along these lines; e.g., “How to Connect With Customers” or “5 Ways to Connect With Your Client“.

However, this goal attempts to disguise a desire for control. The leadership wants to control how the organization will “connect with” customers. Such a goal is a one-way street. It ignores the reality that, for healthy relationships, connection is a two-way process.

In contrast, a functional organization makes it easy for customers to connect about their wants and needs.

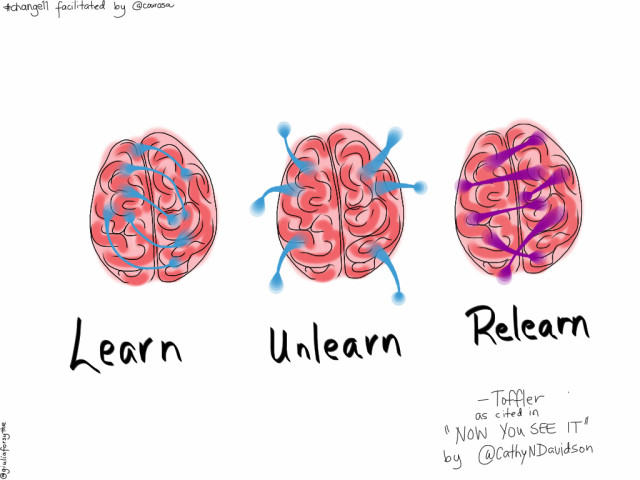

Connection is no longer a goal (noun). A functional organization connects (verb). In the same way that change is a verb, not a noun.

Creating exceptional connection—and organizations

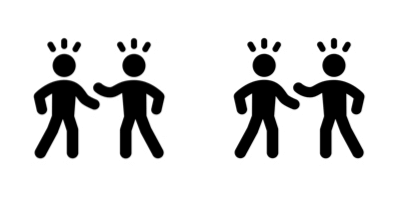

Exceptional organizations take connection to an even higher level. They facilitate connection between their constituency members, supporting the creation of tribes.

Seth, once more:

“When you connect your customers or your audience or your students, you’re the matchmaker, building horizontal relationships, person to person. This is what makes a tribe.”

Tribes—self-organizing groups bound by a common passion—are the most powerful spontaneous human groups. Tribe members pour energy into connecting around their purpose, which leads to meaningful, powerful action. Having them associated with and supported by your organization reaps substantial rewards for everyone involved.

Seek out and create organizations that don’t fear connecting.

You’ll make your world and the world a better place.

Yesterday,

Yesterday,

I find

I find

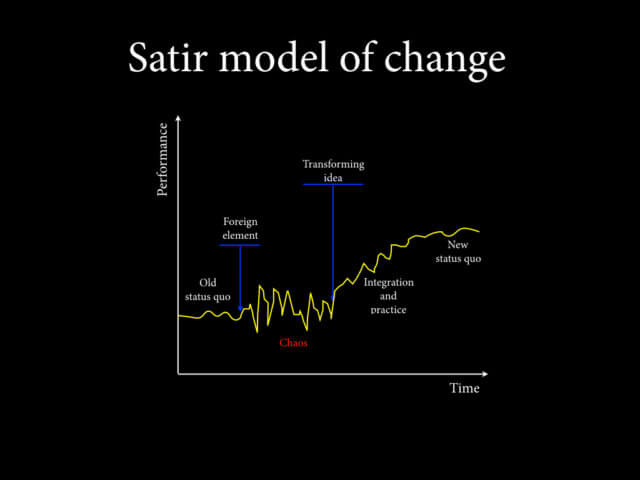

It’s tempting and understandable to concentrate on trying to manage change. After all, we are constantly experiencing change, and attempting to manage it is often unavoidable. But never lose sight of the importance of working on what to change. As Seth Godin reminds us:

It’s tempting and understandable to concentrate on trying to manage change. After all, we are constantly experiencing change, and attempting to manage it is often unavoidable. But never lose sight of the importance of working on what to change. As Seth Godin reminds us: How can we work on facilitating change in our lives?

How can we work on facilitating change in our lives?

How can we successfully work with others for change and action?

How can we successfully work with others for change and action? Watch out for folks who are quick to share opinions about what should be done, but always leave the work they propose to others.

Watch out for folks who are quick to share opinions about what should be done, but always leave the work they propose to others.

How are eventprofs feeling during COVID-19? Over the past few weeks amid the novel coronavirus pandemic, I’ve listened to hundreds of people

How are eventprofs feeling during COVID-19? Over the past few weeks amid the novel coronavirus pandemic, I’ve listened to hundreds of people  I estimate that about 85% of the event professionals I listened to shared feelings of fear, compared to about 65% of the general population. The most common description I heard was anxiety/anxious. But strong expressions like “scared”, “terrified”, and “very worried” were more common than I expected (~5-10%).

I estimate that about 85% of the event professionals I listened to shared feelings of fear, compared to about 65% of the general population. The most common description I heard was anxiety/anxious. But strong expressions like “scared”, “terrified”, and “very worried” were more common than I expected (~5-10%). About half of event professionals, and slightly less of everyone I heard, shared feeling unsettled. “Unsettled” is a mixture of fear and sadness we may feel when we experience the world as less predictable and our sense of control or comfort with our circumstances reduced.

About half of event professionals, and slightly less of everyone I heard, shared feeling unsettled. “Unsettled” is a mixture of fear and sadness we may feel when we experience the world as less predictable and our sense of control or comfort with our circumstances reduced. I was surprised that about half of the general populace mentioned feeling some form of hopefulness about their current situation. Event professionals were far less likely to share feeling this way. This discrepancy is probably because some of the non-event industry people were retirees, and others have escaped significant professional impact.

I was surprised that about half of the general populace mentioned feeling some form of hopefulness about their current situation. Event professionals were far less likely to share feeling this way. This discrepancy is probably because some of the non-event industry people were retirees, and others have escaped significant professional impact. Unlearning is crucial for change.

Unlearning is crucial for change. Events operate by stories.

Events operate by stories.