Do they want to be here?

We’re at a workshop, conference, or session. Do I want to be here? Do they want to be here?

Sometimes we simply don’t.

Swap the perspective

Now, you are leading a workshop, conference, or session. It’s very likely there are people present (perhaps a majority, perhaps all of them) who don’t want to be there.

How can you best serve them?

Here’s a simple answer.

A helpful exchange

A month ago, experiential trainer Shannon Hughes asked members of Facebook’s Applied Improvisation Network private group for thoughts about her frustrating experience running a workshop.

Here’s what she wrote:

“Just finished a 90-min workshop that was like pulling teeth from start to finish. Visibly distracted, clearly checking emails, no engagement or dialogue during debrief. I’m exhausted!

I know it’s no reflection on me, but I can’t help wondering if this is at all “telling” of the way the session was marketed to participants beforehand and/or whether it’s a sign these are not my ideal client.

Am I naive or acting a martyr for asking these questions? I’d love to get a convo going around how we manage our own expectations and energy when our sessions fall flat.

Thoughts?

Yours truly.

Shannon Hughes“

A helpful comment

Among many great comments, Edward Liu‘s stood out.

“Lot of good suggestions so far. The only thing I can add is from one of the best work trainings I ever did, where the first thing the instructor asked was, “who’s here because they want to be and who’s here because they were told to be?” The majority were “told to be,” which she acknowledged and said, “I was told to be here, too, here’s what I suggest to make our experience a little better for the 2 days we all have to be here” and then outlined her expectations and some basic ground rules. I can’t even remember what they were, because I was so struck by an instructor acknowledging that maybe we didn’t really want to be in the class.

She was good enough that we all wanted to be there after an hour or two, and also happened to teach a bunch of management techniques that I can now frame in applied improv terms. But I’d say her very first question was itself an improv technique: Listen to your partner, recognize what they want, and then do your best to give it to them. More often than not, trying to do that means they’ll reciprocate. In this case, your partner is the whole class and you can use the question to intuit what it is they actually want vs what you were hired to do, and then improv your way to ensuring you both get to group mind about the session as a whole as soon as you can.” [Emphasis added.]

Lots of good stuff! Here’s my take.

How to work with folks who don’t want to be here

1. Ask the key question that Edward shared:

At the start of your workshop, conference, or session, ask who chose to be here and who was told they had to be.

2. If there are people who don’t want to be here, then immediately sympathize with them! If possible and appropriate, gently find out why they had to attend.

3. Next, explore what you might be able to do to optimally meet attendees’ wants and needs:

Perhaps you can modify your workshop or session appropriately. In some cases, the Powers That Be may prescribe the entire curriculum, and there’s little or nothing you can do. But in most cases, you’ll have some latitude to adjust what happens while you’re together. If so, first use pair share to get participants thinking about what they’d ideally like to happen. Then run Post It! to hear what they’ve come up with and create a revised plan that takes the expressed wants and needs into effect.

This work is well worth doing if only to let attendees know that you’re thinking about their wants and needs right from the start. But you can almost always improve your time together by simply asking Edward’s opening question and responding sensitively to the answers you receive.

A closing story

I once taught Computer Science for a decade at a small liberal arts college. Every year, I’d teach an introductory class. One year, the class felt very different. Students were more disengaged than usual. The whole classroom environment seemed different. It took me a few weeks before I was bold enough to share my experience with the students. When I did so, I learned that a third of the class was there to fulfill a degree requirement I didn’t know about, imposed by a new joint degree program with another institution. At every class I’d taught previously, all the students had chosen my class voluntarily. I was getting a crash course in teaching students who didn’t want to be here.

I wish I’d thought to ask my students at the first class why they were there. Perhaps I could have made the class a bit better for those who had no choice.

If you are leading a workshop or session and have any suspicion that some attendees may not want to be there, ask them! Your experience and theirs may be all the better for it!

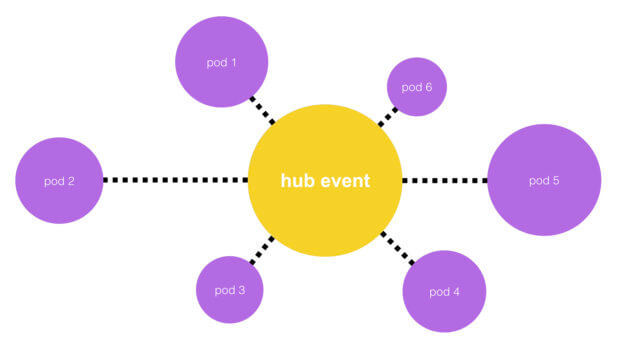

Hub and spoke is an event

Hub and spoke is an event

Is the end of an event important?

Is the end of an event important?