From broadcast to learning in 25 minutes

From broadcast to learning in 25 minutes

Last week’s Green Meetings Industry Council’s 2014 Sustainable Meetings Conference opened with a one-hour keynote panel: The Value of Sustainability Across Brands, Organizations and Sectors. Immediately after the presentation, my task was to help over two hundred participants, seated at tables of six, grapple with the ideas shared, surface the questions raised, and summarize the learning and themes for deeper discussion.

Oh, and I had twenty-five minutes!

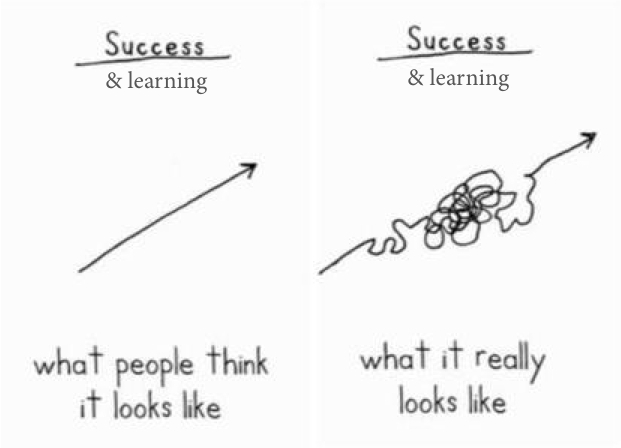

For a large group to effectively review and reflect on presented material in such a short time, we have to quickly move from individual work to small group work to some form of a concrete visual summary that’s accessible to everyone.

Here’s what I did

[Added August 2023: I documented this entire process, named RSQP, in more detail in my book Event Crowdsourcing.]

Stand up!

1) My audience hadn’t moved for over an hour, and their brains had, to varying degrees, gone to sleep. So, for a couple of minutes, I had people stand, stretch, twist, and do shoulder rolls.

Explain!

2) Next, I summarized what we were about to do. I

-

-

- Outlined the three phases of the exercise: a) working individually; b) sharing amongst the small group at their table, and c) a final opportunity to review everyone’s work in a short gallery walk.

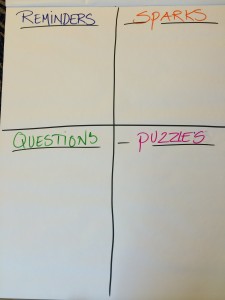

- Pointed out the tools available. Each table had a sheet of flip-chart paper (divided into a 2 x 2 matrix), 4 pads of different colored sticky notes, and a fine-tip sharpie for each person.

-

-

-

- Explained the four categories they would use for their responses. After introducing each category I asked a couple of pre-primed volunteers to share an example of their response with the participants.

- REMINDERS. “These are themes with which you’re already familiar that the keynote touched on. You might want to include ideas you think are important. And you might want to include themes that you have some expertise or experience with. More on that in a moment. Write each REMINDER on a separate blue sticky note, which will end up in the top left square of the flip chart.”

- SPARKS. “Sparks are inspirations you’ve received from the keynote; new ideas, new solutions that you can adopt personally, or for your organization, or at your meetings. Write your SPARKS on yellow sticky notes; they’ll go in the top right square.

- QUESTIONS. “These are ideas that you understand that you have questions about. Perhaps you are looking for help with a question. Perhaps you think a question brought up by the keynote is worth discussing more widely at this event. Write your questions on a green sticky note; they’ll go in the bottom left square.

- PUZZLES. “Puzzles are things you feel that you or your organization or our industry don’t understand and need help with. Write your puzzles on a violet sticky note; they’ll go in the bottom right.”

- Gave these instructions. “In a minute I’m going to give you about five minutes to work alone and create your REMINDERS, SPARKS, QUESTIONS, and PUZZLES. Don’t put your notes on the flip chart paper yet; we’ll do that communally soon. Any questions?” [There were none.] “Two final thoughts:

- 1) Words are fine, but feel free to draw pictures or diagrams too!

- 2) Consider adding your name to any of your notes. We’re going to display your notes on the wall over there. If you have expertise or experience in one of your themes, adding your name to your note will allow others who are interested in the topic to find you. Have a question or puzzle you need help with? Adding your name will allow others who can help to find you.”

- Explained the four categories they would use for their responses. After introducing each category I asked a couple of pre-primed volunteers to share an example of their response with the participants.

-

Get to work alone!

3) I gave everyone five minutes to create their notes, asking them to shoot for a few responses in each category.

Share at your table!

4) For the second phase of the exercise, I asked each person to briefly explain their notes with the others at their table, placing them on the appropriate quadrant of the flip chart as they did so. I allocated each person a minute for this and rang a bell when it was time for the next person to begin.

Review everyone’s work!

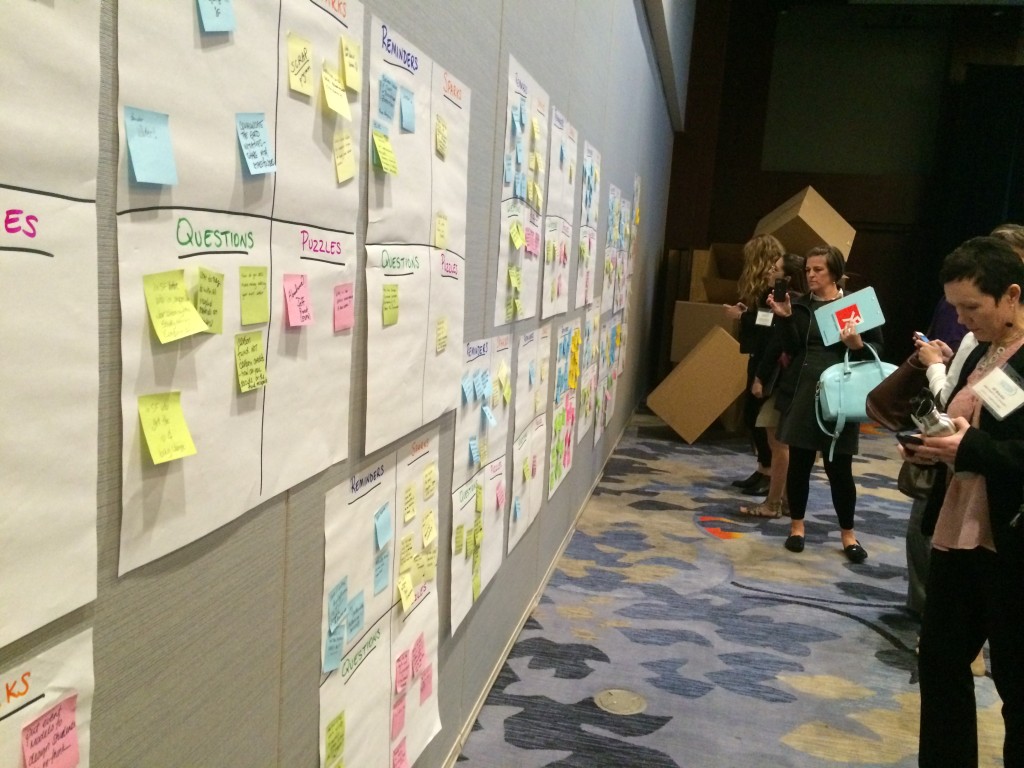

5) The final phase was a gallery walk. I asked one person from each table to go and stick their flip chart page on a large blank meeting room wall. Once done, I invited everyone to go to the gallery and explore what we had created together.

The results

Here’s one end of the resulting sharing wall.

6) Later that evening I had a small number of subject matter experts cluster the themes they saw. (If I had had more time, I would have had all the participants work on this together during my session.) The resulting clusters were referred to throughout the conference for people to browse and use as a resource. Here’s a picture, taken later, showing the reclustered items in our “sharing space”.

Yes, you can go from broadcast to learning in 25 minutes! Even when time is short, an exercise like this can quickly foster huge amounts of personal learning, connection (via the table work and named sticky notes), and audience-wide awareness of interests and expertise available in the room. Use reflective and connective processes like these after every traditional presentation session to maximize their value to participants.

Conferences need to be flexible!

Conferences need to be flexible! No one knew how to “teach programming” to fifteen-year-old kids then. Our teachers just handed us an

No one knew how to “teach programming” to fifteen-year-old kids then. Our teachers just handed us an