Why measurable outcomes aren’t always a good thing

What could be wrong with requiring measurable outcomes?

“Enough of this feel-good stuff! How do we know whether people have learned anything unless we measure it?”

—A little voice, heard once in a while in learning designers’ heads

Ah, the lure of measurement! Yes, it’s important. From a scientific perspective, a better understanding of the world we live in requires doing experiments that involve quantifying properties in a statistically meaningful and repeatable way. Science has no opinion about ghosts, life after death, and astrology, for example, because we can’t reliably measure associated attributes.

The power of scientific thinking became widely evident at the start of the twentieth century. It was probably inevitable that it would be applied to management. The result was the concept of scientific management, developed by Frederick Winslow Taylor. Even though Taylorism is no longer a dominant management paradigm, its Victorian influence on how we view working with others still persists to this day.

But we can’t measure some important things

I’m a proponent of the scientific method, but it has limitations because we can’t measure much of what’s important to us. (Actually, it’s worse than that—often we aren’t even aware of what’s important.) Here’s Peter Block on how preoccupation with measurement prevents meaningful change:

The essence of these classic problem-solving steps is the belief that the way to make a difference in the world is to define problems and needs and then recommend actions to solve those needs. We are all problem solvers, action oriented and results minded. It is illegal in this culture to leave a meeting without a to-do list. We want measurable outcomes and we want them now…

…In fact it is this very mindset, one based on clear definition, prediction, and measurement which prevents anything fundamental from changing.

—Peter Block, Community: The Structure of Belonging

One of my important learning experiences occurred unexpectedly in a workshop. A participant in a small group I was leading got furious after something I had said. He stood up and stepped towards me, shouting and balling his fists. At that moment, to my surprise, I knew that his intense anger was all about him and not about me. Instead of my habitual response—taking anger personally—I was able to effectively help him look at why he had become so enraged.

There was nothing measurable about this interchange, yet it was an amazing learning and empowering moment for me.

The danger of focussing on what can be measured

So, one of the dangers of requiring measurable outcomes is that it restricts us to concentrating on what can be measured, not what’s important. Educator Alfie Kohn supplies this example:

…it is much easier to quantify the number of times a semicolon has been used correctly in an essay than it is to quantify how well the student has explored ideas in that essay.

—Alfie Kohn, Beware of the Standards, Not Just the Tests

Another reason why we fixate on assigning a number to a “measured” outcome is that doing so can make people feel they can show they’ve accomplished something, masking the common painful reality that they have no idea how to honestly measure their effectiveness.

Measured learning outcomes can be relevant if we have a clear, performance-based, target. For example, we can test whether someone has learned and can apply cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) by testing them in a realistic environment. (Even then, less than half of course participants can pass a skills test one year after training.)

This leads to my final danger of requiring measurable outcomes. It turns out that measurements of learning outcomes aren’t reliable anyway!

For nearly 50 years measurement scholars have warned against pursuing the blind alley of value added assessment. Our research has demonstrated yet again that the reliability of gain scores and residual scores…is negligible.

—Professor Trudy W. Banta, A Warning on Measuring Learning Outcomes, Inside Higher Ed

Given that requiring measurable outcomes often inhibits fundamental change and is of dubious reliability, I believe we should be considerably more reluctant to insist on including them in today’s learning and organizational environments.

[This post is part of the occasional series: How do you facilitate change? where we explore various aspects of facilitating individual and group change.]

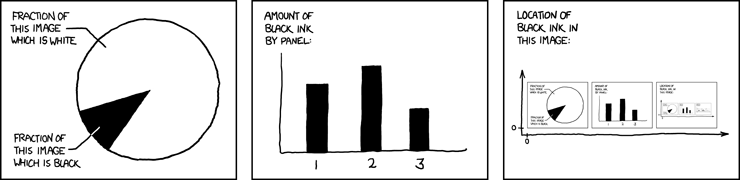

Image attribution: xkcd