Nine practical tips for letting go in a chaotic world

I’ve no guarantees, but here are nine suggestions that almost always work for me.

1 — Notice what’s going on

Yes, we need to shut up and listen to what people say. And we need to notice what they do. But what is often harder is to listen to and notice ourselves. To notice:

- What we’re doing;

- How what we’re doing is affecting what we’re thinking and, especially, feeling; and

- How what we’re thinking and feeling is affecting what we’re doing.

A simple personal example is noticing I feel angry about a small irritation, like accidentally dropping something I’m holding. When I’m centered, an incident like that is no big deal. But when I respond with an expletive, that’s a sign that something else is going on. I’m likely carrying some anger that has nothing to do with my fumble.

Without noticing what’s going on with ourselves, we’re unlikely to be capable of letting go of anything that isn’t serving us well.

2 — Meditate regularly

Regular meditation is the key to giving me practice and supporting my need/want/desire to let go of what isn’t serving me in the moment. Though I struggled to meditate daily for many years, I’ve finally developed a daily meditation practice that serves me well. I also try to meditate when I notice incongruence in my responses to experiences (see above).

3 — “Nothing to get. Nothing to get rid of.”

While meditating, thoughts and (sometimes) feelings appear. When this happens, reminding myself that there’s “Nothing to get. Nothing to get rid of.” calms me and helps me empty my mind.

4 — “Is it necessary?”

The question “Is it necessary?” is a useful tool to examine a disturbing thought that captures your attention.

Do I need to be thinking this thought right now 😀?

Usually, the answer is “no”!

5 — Remember who you are

I have a contract with myself that I developed in 2005. Sometimes, I notice that I’m circling through thoughts and feelings about a fantasized future that is unrelated to the current moment. I remind myself of my contract — who I really am — by mentally repeating it to myself. This helps me center and stop clinging to unhealthy and unproductive thoughts and feelings.

6 — Greet what comes up with compassion

You can’t force letting go. Instead, you can accept the reality of what is happening. One way to do this is to greet what comes up with compassion. Compassion is a form of acceptance that can allow persistent thoughts and feelings to lose their force.

6 — “Let John be John.”

Sometimes you find yourself feeling worried, upset, or angry due to the actions of a specific person that affect you. A helpful way to get some distance and relief from these feelings and associated thoughts is to accept that they are the way they are. Saying to yourself “Let John be John” (substitute their name for “John” 😀) acknowledges that:

- They are not you.

- How they interact with you is always about them, and often, not about you.

- You accept their reality without it necessarily affecting yours.

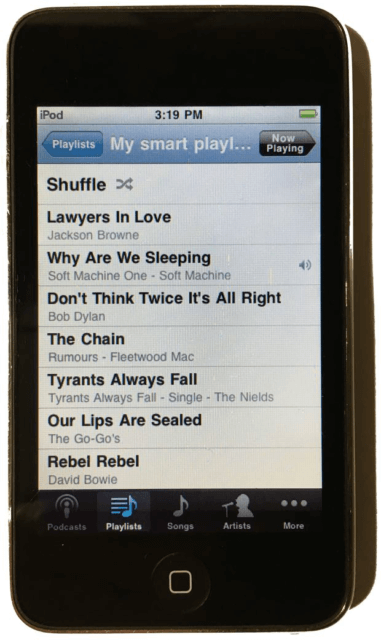

7 — Use music

Music has the strange power to change our emotional state. I don’t know of a better way to move away from persistent distracting thoughts and feelings than by listening (and sometimes dancing) to music that I love.

8 — Other concepts that may help you.

I’m using imperfect words to convey helpful approaches to letting go. Here are some other words and phrases that may strike a chord for you:

- Acceptance

- Loosening

- Surrendering

- Releasing

- Noticing the burden

- Clinging is suffering; letting go ends suffering

- Letting go is a form of love

- Letting go is an ongoing practice and process

- Letting things be as they are

9 — Finally, be kind to yourself!

We are all imperfect realizations of our perfection. I fail at all the above repeatedly. When the renowned cellist Pablo Casals was asked why, at 81, he continued to practice four or five hours a day, he answered: “Because I think I am making progress.” So, be kind to yourself!

What practical tips do you have to help you let go in this chaotic world? Please share in the comments below!

Image attribution: “The image Let Go” by JFXie is licensed under CC BY 2.0 .

Can a rehearsal be better than a concert? You be the judge!

Can a rehearsal be better than a concert? You be the judge!

Should we play music at conference socials?

Should we play music at conference socials?

For the last three months, I’ve been rehearsing for the

For the last three months, I’ve been rehearsing for the