Interaction is at the heart of cognition—and events!

Here’s the paper: “Beyond Single-Mindedness: A Figure-Ground Reversal for the Cognitive Sciences.”

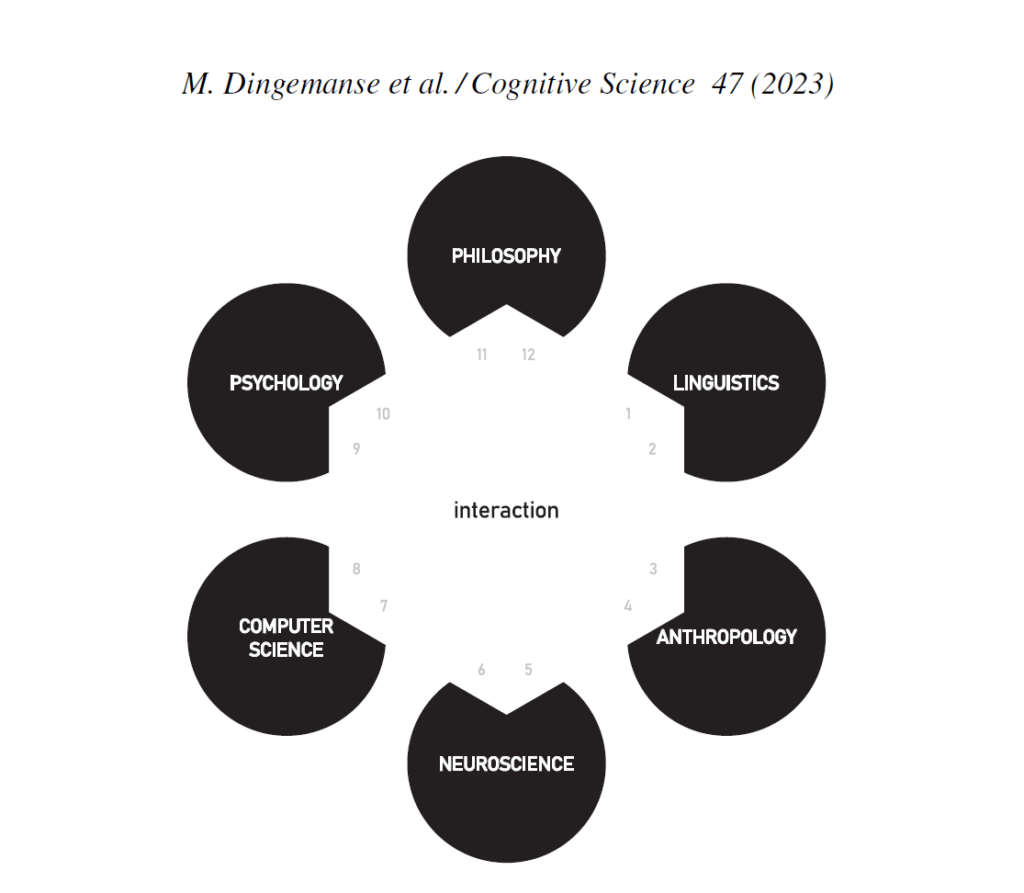

Dingemanse et al_2023_Beyond Single-MindednessThey go on to describe this new viewpoint as a “figure-ground reversal that puts interaction at the heart of cognition.” Mark Dingemanse explains and illustrates the deliberate use of “figure-ground” as follows:

“Why a figure-ground reversal rather than a ‘paradigm shift’ or an ‘interactive turn’? This is both a nod to the roots of cognitive science and a rhetorical choice: we think of the interactive stance as a perspective — a way of seeing that deserves to be a key part of the conceptual toolkit of cognitive scientists

Is there a hexagon below, or whitespace bounded by circular sectors? Gestalt switches are reversible, but hard to unsee. We want to make interaction ‘hard to unsee’ for @cogsci.”

For more details, check out Dingemanse’s website: Beyond Single-Mindedness.

Interaction is at the heart of cognition—and events!

For decades I’ve been designing meetings that support meaningful interaction to create successful learning and connection. Sadly, integrating interaction into meeting sessions is still the exception rather than the rule at most meetings, which are places where learning is restricted to listening to experts lecturing, and connecting around relevant content is relegated to hallways, meals, and socials.

Such traditional meeting models are based on cognitive learning as something that is done to a set of individual brains.

So I’m heartened to see scientists adopting a view of cognition as something that arises through interactions between people. And it doesn’t surprise me. After all, as the paper points out:

“A fundamental fact about human minds is that they are never truly alone: all minds are steeped in situated interaction.”

—Mark Dingemanse et al, Beyond Single-Mindedness: A Figure-Ground Reversal for the Cognitive Sciences, Cognitive Science, January 10, 2023

I continue to believe that interaction around meaningful content is at the heart of events. And now there’s a little extra scientific support as well!

Should we play music at conference socials?

Should we play music at conference socials? Please don’t call me a speaker. Yes, anyone who’s met me knows I like to talk. It’s true: I have been accused (justifiably at times) of talking too much. Yes, I get invited to “speak” at many events.

Please don’t call me a speaker. Yes, anyone who’s met me knows I like to talk. It’s true: I have been accused (justifiably at times) of talking too much. Yes, I get invited to “speak” at many events.