Panels as if the audience mattered

I’m in San Antonio, Texas, having just run two 90-minute “panels” at a national association leadership conference. I say “panels” because in both sessions, the three “panelists” presented for less than five minutes. Yet after both sessions, participants stayed in the room talking in small groups for a long time. That’s one of my favorite signs that a session has successfully built and supported learning, connection, and engagement.

You may be wondering how to effectively structure a panel where the panelists don’t necessarily dominate the proceedings. How can we let attendees contribute and steer content and discussion in the ways they want and need? There’s no one “best” way to do this of course, but here’s the format I used for these two particular sessions.

Session goals

Each session was designed to discover and meet the wants and needs of the executive officers and volunteers of the association’s regional chapters’ members in an area of special interest. The first session focused on a key fundraising event used by all of the participants. The second covered the more general topic of chapter fundraising and sponsorship.

Room set

Room set has a huge effect on the dynamics of a session. Previous sessions in our room had used head tables with table mikes and straight-row theater seating (ugh; well, at least it was set to the long edge of the thin room.) I had the tables removed, the mikes replaced with hand mikes, and the chairs set to curved rows. We included plenty of aisles so that anyone could easily get to the front to speak (see below).

Welcome and a fishbowl sandwich

After a brief welcome and overview, I began a four-chair fishbowl sandwich format, which turns every attendee into a participant right at the start, and ensures that they end up participating too. This format is my favorite way to create amazing panels. Fishbowl allows control over who is speaking by having them move to a chair at the front of the room. Check the link for a description of this simple but effective way to bring participation into a “panel”.

Body voting

Next, I used body voting, to give participants relevant information about who else was in the room. For example, I had everyone line up in order of chapter size, so people could:

- discover where they fit in the range of chapters present (from 80 to 2,600 members);

- meet participants whose chapters were similar in size to their own; and

- give everyone a sense of the distribution of chapter sizes represented.

Additional body votes uncovered information about:

- revenue contributions from dues, events, and sponsorship;

- promotional modalities used;

- member fees; and

- other issues related to the session topic.

I also gave participants the opportunity to ask for additional information about their peers in the room. This is another powerful way for participants to discover early on that they can determine what happens during their time together. I used appropriate participatory voting techniques (see also here, and here) to get answers to the multiple requests that were made.

Panelist time!

Several weeks before the conference, I scheduled separate 30-minute interviews with the six panelists to educate myself about the issues surrounding the session topics and to discover what they could bring to the sessions that would likely be interesting and useful for their audience. After the interviews were complete, I reviewed our conversations and determined that each panelist could share the core of their contributions in five minutes. So I asked each panelist to prepare a five-minute (maximum!) talk that covered the main points they wanted to make.

During the first session, I brought up the panelists to the front of the room individually. As each panelist gave their talk, I allowed questions from the audience, and, as I should have expected, each panelist’s five minutes expanded (by a few minutes) as they responded to the questions. So for the second session, I tried something different. All three panelists sat together with me, and I asked the audience to hold questions until all three had finished. Each panelist gave a five-minute presentation, and then I facilitated the questions that followed.

In my opinion, having only one panelist at the front of the room at a time creates a more dynamic experience. But on balance, I think the second approach worked better as there was some overlap between what the panelists shared, and when questions ended there was a more natural segue to the next segment of the session.

Fishbowl

At this point, we switched to a fishbowl format. I had the panelists return to front-row audience chairs, from where they could easily return to the “speaking” chairs. (They were frequent contributors to the discussions that followed.) I identified some hot issues and listed them for participants. I then invited anyone to sit in one of the three empty front-of-the-room chairs next to me to share their innovations, solutions, thoughts, questions, and concerns. Anyone wishing to respond or discuss joined our set of chairs and I facilitated the resulting flow of conversation. Some of the themes I suggested were discussed. But a significant portion of the discussion in both sessions concentrated on areas that none of my panelists had predicted.

The capability of the fishbowl process to adapt to whatever participants actually want to talk about is one of its most attractive and powerful features. If I had used a conventional panel for either session, much more time would have been spent on topics that were not what the audience most wanted to learn about, and unexpected interests would have been relegated to closing Q&A.

Consulting

During my opening overview of the format, I explained that we might have time for some consulting on a participant’s problem toward the end of the session. We didn’t have time for this during the first session — given a break, we could have probably taken another hour exploring issues that had been raised — but we had a nice opportunity during the second session to consult on an issue for a relatively new executive officer.

Another option that I offered, which we didn’t end up exploring in either session, was to share lessons learned (aka “don’t do this!”) — a useful way to help peers avoid common mistakes.

Closing

With a few minutes remaining, I closed the fishbowl and asked participants to once again form pairs and share their takeaways from the session. The resulting hubbub continued long after the sessions were formally over, and I had to raise my voice to thank everyone for their contributions and declare the sessions complete.

When an audience collectively has significantly more experience and expertise than a few panelists — as was the case for these sessions (and a majority of the sessions I’ve attended during forty years of conferences) — well-facilitated formats like the one I’ve just described are far more valuable to participants than the conventional presentations and panels we’ve all suffered through over the years. Use them to create amazing panels, and your attendees will thank you!

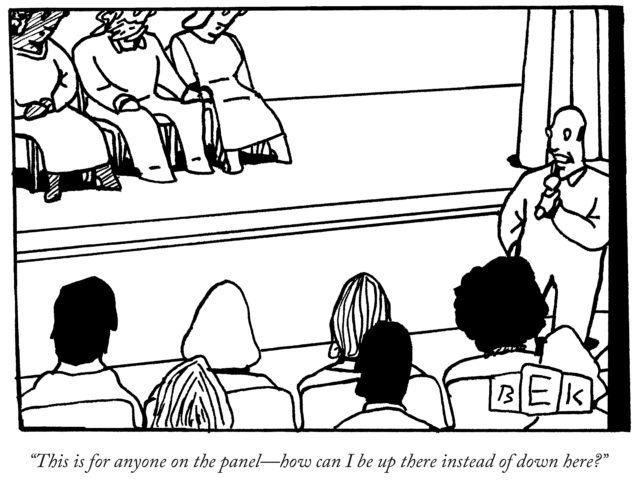

Create amazing panels!

At the conference sessions I design and facilitate, everyone is “up there” instead of “down here.” Yours can be too! To learn how to build sessions that build and support learning, connection, and engagement, sign up for one of my North American or European workshops.

Bruce Eric Kaplan cartoon displayed under license from The Cartoon Bank

Ten minutes after I’d finished facilitating a large national association meeting hour-long fishbowl sandwich discussion on solutions for a persistent industry problem, the conference education director walked in. His jaw dropped. “The attendees are still here talking to each other! That never happens!” he exclaimed.

Ten minutes after I’d finished facilitating a large national association meeting hour-long fishbowl sandwich discussion on solutions for a persistent industry problem, the conference education director walked in. His jaw dropped. “The attendees are still here talking to each other! That never happens!” he exclaimed.