Look up “voting” on Google and the top search results are dominated by links about electoral voting. Making decisions (about elected leaders, opposing choices, action plans, etc.) is the first function of voting that comes to mind for most people.

In a participatory meeting environment, however, voting is most useful as a way to obtain information early in the process. It provides a “straw poll” that provides public information about viewpoints in the room and paves the way for further discussion. I call such process participatory voting.

Ways to use participatory voting

Perhaps surprisingly, voting is not a simple, well-defined process. The International Society on Multiple Criteria Decision Making lists more than four thousand articles on decision theory in its bibliography. Voting, it turns out, can be a complex and subtle business.

For most of us, “group voting” brings up the concept of voting as decision-making. But voting can be used to test learning and to elicit and share information. To guide your choice of the participatory voting techniques I’ll cover in later posts, here are short descriptions of various ways to use voting in meeting sessions.

Determining consensus

It’s often unclear whether a group has formed a consensus around a specific viewpoint or proposed action. Consensual participatory voting can quickly show whether a group has reached or is close to consensus, or wants to continue discussion. It can also pinpoint those who have significant objections to a majority position and give them the opportunity to clarify their reasons for opposition.

Making decisions

How people use voting techniques depends a lot on their presentation/facilitation/management style. If you are focusing on making a decision, voting is a tempting method to obtain an outcome. But if a vote is held prematurely, before adequate exploration of alternatives and associated discussion, the “decision” may have poor buy-in from those who voted in the minority or who feel they weren’t heard. People will rightly feel ambushed if they are asked to vote on a decision without adequate warning and opportunities for discussion.

Thus, if you plan to use voting for decision-making, explain up front the processes and time constraints you will be using before the vote. Unless the vote is purely advisory, give participants the chance to determine what they will be voting on, and how it will be framed. Such preparation lets people know their opportunities to shape discussion, and minimizes the likelihood that unexpected premature voting will cut off exploration of important creative or minority options.

Testing learning

Polling an audience is a time-tested technique, as old as teaching itself, for teachers to obtain feedback on student understanding. “Pop” quizzes, multiple-choice tests, and modern Audience Response Systems can be useful ways to test audience learning. But they have their limitations. As Jeff Hurt explains:

“[Audience Response Systems] are good for immediate feedback. They are good for ‘knowledge learning.’ Studies show they increase engagement and let someone know whether their answer is right or wrong. In short, they are good for surface knowledge. They however do not promote deep learning…which leads to higher level thinking skills such as estimation, judgement, application, assessment and evaluation of topics.”

—Facebook comment by Jeff Hurt

The participatory learning philosophy I espouse concentrates on these deeper learning skills. From this perspective, traditional voting supplies limited information when used as a testing tool.

Setting context

We know that small group discussion is key to effective learning during an event. But how do we set an initial context for discussion? Participatory voting techniques supply important information about the views, preferences, and experiences of participants, both as a group and as individuals. You can then use this information to set up appropriate discussions.

Eliciting information

Perhaps the most important benefit of participatory voting techniques is their ability to elicit important information about the people, needs, and ideas in a group and make it available to the entire group. Although you can use some voting techniques to provide anonymous or semi-anonymous information, I believe that sharing information provided by group members to group members is one of the most powerful ways to strengthen connection, openness, and a sense of community in a group.

Allowing participants to discover those who agree or disagree with them or share their experience efficiently facilitates valuable connections between participants in ways unlikely to occur during traditional meetings. Giving group members opportunities to harness these techniques for their own discoveries about the group can further increase engagement in the group’s purpose.

Determining the flow of group conversation and action

Participatory voting techniques such as card voting provide large groups the real-time feedback required to productively steer a complex conversation to best meet the needs of the group.

Planning action

Finally, we can use participatory voting to uncover group resources, interest, and commitment on specific action items from individual participants.

Some concluding observations about voting

If you’re using voting to test understanding of a concept or explore a group’s knowledge of a topic, include time for small group discussion before the vote. Pair share is a great technique for this. Provide enough time for each participant to think about their answer and then have them pair share their understanding. After the vote, you can facilitate a discussion with the entire group about the differences uncovered.

To avoid making premature decisions, use consensual voting to uncover significant alternative viewpoints. Test the depth of agreement before confirming that you have substantial agreement through decision-oriented voting.

Think about when and how you use voting. Voting on alternatives that have been inadequately explored or discussed is counterproductive.

Use public voting methods whenever appropriate—which is, in my experience, most of the time.

If people wish to “sit out” their vote when using participatory voting, support their right to do so. (Unless you are testing for consensus, in which case it’s reasonable to ask for their feedback.) Consider using anonymous voting if people seem reluctant to express an opinion.

[This post is adapted from a (longer) chapter on participatory voting in The Power of Participation: Creating Conferences That Deliver Learning, Connection, Engagement, and Action.]

Read more about participatory voting at events in Part 2 and Part 3!

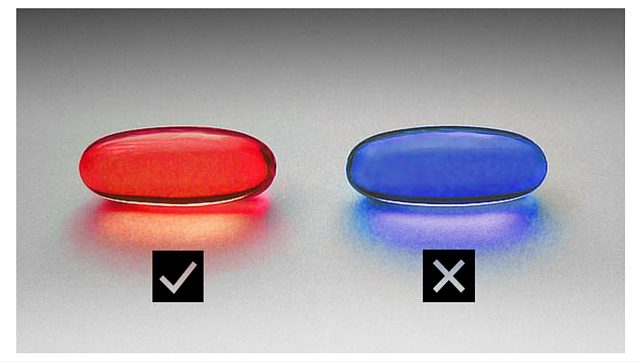

Red pill blue pill image modified by yours truly, attribution W.carter under CC BY-SA 4.0 license

Hi Adrian.

May I ask why you feel public voting methods are appropriate most of the time?

I worry about bandwagon, group think, peer pressure, social dynamics, etc. affecting how sincerely people vote if their opinion is public… especially when their boss or friends are in the room.

You have probably answered this else ware – maybe point me to the link?

Thanks so much!

Hi Jason,

Actually I haven’t written about this issue directly. This point of view is a function of the kind of group work I do, and the environment I do it in.

I think that you facilitate mainly public group work, where anyone can show up (your boss, your friends), where anything you say might be broadcast live or recorded and made available to unknown others later. Under such circumstances, it’s entirely appropriate to worry about the sometimes real repercussions of others knowing opinions you express, and anonymous voting may well be the best choice to obtain accurate information while maintain voters’ internal or external safety.

I tend to work more with communities of practice, typically association members, in situations where there is no media present, or the media is willing to agree to keeping individual POVs off the record unless an individual specifically agrees otherwise. In these environments, although there are obviously situations where some people may not want to share frank opinions (perhaps their boss is present) I’ve found that public voting is, on balance, far more useful for overall learning and for making fruitful connections amongst participants.

One more comment and resource. When participants in such gatherings are clearly worried about the ramifications of frank discussions, that is often the most useful place to work. Jeffrey Cufaude has an excellent article on the topic: http://www.ideaarchitects.org/2016/05/when-honesty-seems-risky.html