The danger of our drive to make sense

Nick Chater and George Loewenstein propose that evolution has produced a ‘drive for sense-making’. They argue that sense-making…

- …is a fundamental human motivation.

- …is a drive to simplify our representation of the world.

- …is traded off against other ‘utilitarian’ motivations.

- …helps to explain information avoidance and confirmation bias.

—The under-appreciated drive for sense-making, Nick Chater and George Loewenstein, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization

Clearly, sense-making is a vital human activity. At a fundamental level, our brains are continuously, and largely automatically, making sense of our sense organ data. At higher levels of thought, we routinely attempt to make sense of situations that confront us. If we didn’t, the world would be a confusing and perpetually dangerous place.

Our sense-making prowess allows us to build models of the present and make decisions about potential future behavior. Thus, sense-making is a key ingredient of our ability to plan and make group decisions.

The danger of our drive to make sense

There’s a flip side to our incredible ability to make sense of our perceptions and experiences. Dave Snowden, speaking about tactics used by the foresight community, says:

“The real dangers are retrospective coherence and premature convergence“

—Dave Snowden, Of tittering, twittering & twitterpating

Retrospective coherence

Dave Snowden coined the term retrospective coherence, aka Monday morning quarterbacking, when talking about the behavior of complex systems. (See Dave Snowden and Mary Boone’s classic article A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making to learn more about complex systems, a domain of the Cynefin framework.) Retrospective coherence means that, in a complex environment, it seems easy in hindsight to explain why things happened. Unfortunately, applying our sense-making abilities to complex systems doesn’t work, since cause and effect can only be determined in retrospect.

For those with short memories, the danger of retrospective coherence is that it inspires false confidence in their ability to make correct predictions. To avoid such inflation of our predictive expertise we need to scrupulously compare our predictions with actual outcomes, and admit our limitations.

Premature convergence

Premature convergence is our predilection to prematurely decide we have found the answer to a problem and stop exploring other possibilities.

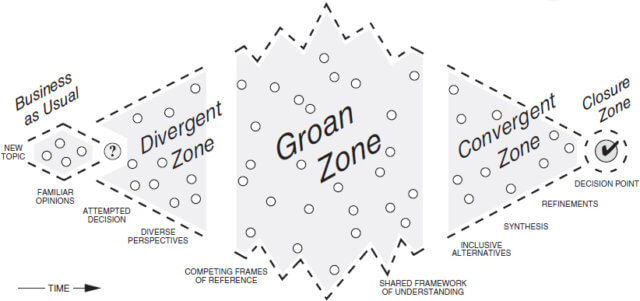

Facilitators are familiar with this human tendency, and minimize it by spending adequate time in what Sam Kaner calls the Divergent and Groan Zones.

Determining what is “adequate” time is one of the arts of facilitation.

During divergence, a facilitator supports the uncovering of relevant questions, information, perspectives, and ideas.

At some point, there’s a switch to the Groan Zone. Here, the participants discuss what’s been uncovered, develop a shared framework of understanding, and create inclusive potential solutions. At least, that’s how Kaner describes the process, though the Groan Zone has always seemed to me to have a lot in common with what Virginia Satir’s change model calls chaos.

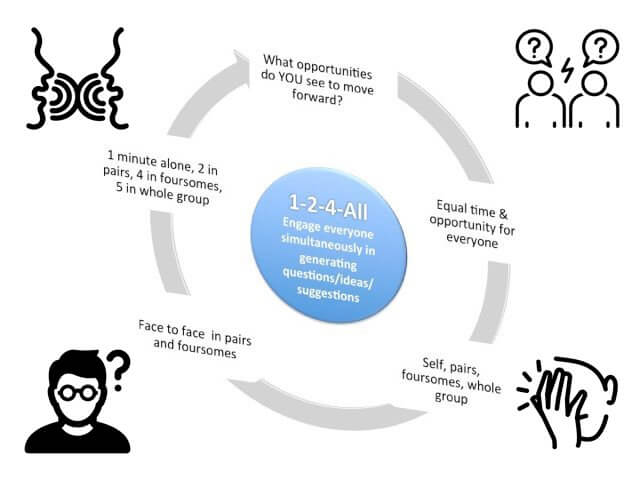

People have proposed many ways to move from groan zone to convergence, and some of them are flawed. There’s no single “right” way to move to convergence. But you’re likely guaranteed to come up with a poor conclusion if you don’t spend enough time diverging and groaning beforehand.

Stop making sense?

Despite the pitfalls outlined above, we are sense-making animals and I wouldn’t want it any other way. Stay realistic about your limitations to predict future outcomes, and take your time moving through the divergent & Groan Zone processes, and you’ll avoid the dangers of our drive to make sense.

Mostly.

While

While