How to trust your gut

Three stories and a presentation about “How to trust your gut”.

1 • My gut meets Seth Andrew

Last week, I was about to begin an online presentation on “How to trust your gut” when a national story broke. Major news outlets (1, 2, 3) were reporting that Seth Andrew, founder of a national network of charter schools, had been arrested for allegedly stealing $218,000 from one of the schools: Democracy Prep.

Now it happens that I’ve had an intense set of community interactions with and about Seth Andrew over the last year. I first met him on Facebook on May 28, 2020, where he announced his non-profit, Democracy Builders, had purchased the Marlboro College campus where I taught for ten years.

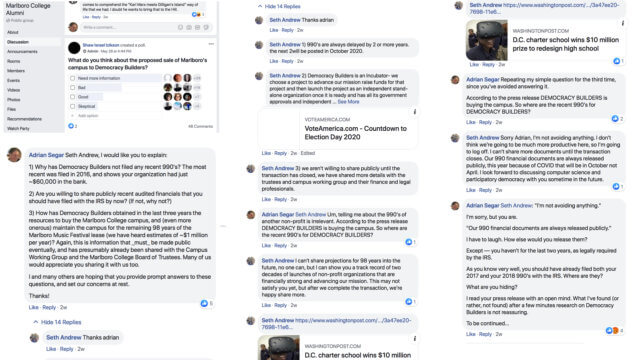

That same day, it took me just thirty minutes to get a gut feeling that this man could not be trusted. I’ve worked in and with non-profits—in board member, volunteer, and consultant roles—for decades. When I asked Seth about Democracy Builders’ missing 990s, the reports that every federally tax-exempt organization has to file with the IRS every year, he was clearly evasive and kept trying to change the subject. (In retrospect, now knowing that Seth is alleged to have stolen government funds the year before and transferred them to the exact non-profit I was asking about supplies a new perspective to his reactions.)

[Click on the image of our conversations below and scroll down to and expand my first post, to see Seth’s evasions in the public Facebook thread.]

I considered adding this illustrative tale to my presentation. But, with ten minutes until showtime and a promise that the talk would take fewer than 21 minutes, I reluctantly omitted this remarkable story about trusting my gut response to Seth Andrew.

Regardless, my presentation includes other personal stories about how trusting my gut has worked out for me.

2 • How to trust your gut

How did I come to be giving this presentation in the first place? Well, a couple of months ago, my friend, the warm and oh-so-talented association maven Kiki L’Italien, invited her Association Chat community members to share anything they wanted to talk about — in just 21 minutes. While reading her invite, “How to trust your gut” somehow popped into my head. I’ve never spoken on this topic before. Nevertheless, trusting my gut, I immediately signed up for a presentation.

During the following weeks, I realized that I had some advice to impart about trusting one’s gut and put together this presentation that you can now watch.

3 • When your gut leads you astray — the story of vaccine hesitancy

As I share in the presentation, sometimes it’s not a good idea to trust your gut. A good example of this is the current issue of vaccine hesitancy: folks delaying acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite the availability of vaccination services.

I’m not going to go into much detail, except to point out that anecdotal stories often win out over facts. While personal stories can be a powerful modality for learning, the steps involved…

- Notice the important story.

- Capture the story.

- Tease out the meaning.

…as described in the post, can be misapplied.

Especially when the stories we hear are untrue.

The reality that…

- getting the COVID-19 vaccine can protect you from getting sick and helps others in your community;

- the fast development of COVID-19 vaccines did not corners on testing for safety and efficacy; and

- side effects of COVID-19 vaccines are temporary

… has been hijacked by deeply held gut beliefs that are the heart of many people’s resistance to getting vaccinated.

For example, research has shown that “[vaccine] skeptics were much more likely than nonskeptics to have a highly developed sensitivity for liberty — the rights of individuals — and to have less deference to those in positions of power. Skeptics were also twice as likely to care a lot about the ‘purity’ of their bodies and their minds.”

Such gut feelings can be very strong, and it’s hard to override them using facts and scientific findings.

Unfortunately, relying on such gut feelings and passing up opportunities to receive a COVID-19 vaccine can have deadly consequences. There are countless stories of COVID-19 deniers dying of COVID-19. Here are a few: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5.

Don’t ignore your gut feelings, but test their veracity!

My presentation includes suggestions on what to do to check the accuracy of your gut feelings.

How to trust your gut—the presentation

Last week, I was a guest on Kiki’s show. In 20 minutes, I shared everything I’ve learned (so far) about how to trust your gut, how trusting your gut can change your life, how to get better at doing it…and when you shouldn’t.

I hope you enjoy it!

Additional presentation resources

Finally, here are two resources I mention during the presentation for learning about the importance of our gut responses. These excellent books explain in detail why our feelings, rather than our cognition generally drive us to act.

- The Happiness Hypothesis: Finding Modern Truth in Ancient Wisdom by Jonathan Haidt introduces the lovely rider and elephant analogy to explain the control relationship between our emotional and rational selves.

- Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman provides a cornucopia of research supporting the above relationship.

What have you learned about trusting your gut? Do you have stories to share? Wisdom to add? Please let us know in the comments below!

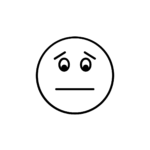

We all have different responses to adversity, and none of them are “wrong”.

We all have different responses to adversity, and none of them are “wrong”. We spend too much time distracting ourselves from what matters.

We spend too much time distracting ourselves from what matters.

How are eventprofs feeling during COVID-19? Over the past few weeks amid the novel coronavirus pandemic, I’ve listened to hundreds of people

How are eventprofs feeling during COVID-19? Over the past few weeks amid the novel coronavirus pandemic, I’ve listened to hundreds of people  I estimate that about 85% of the event professionals I listened to shared feelings of fear, compared to about 65% of the general population. The most common description I heard was anxiety/anxious. But strong expressions like “scared”, “terrified”, and “very worried” were more common than I expected (~5-10%).

I estimate that about 85% of the event professionals I listened to shared feelings of fear, compared to about 65% of the general population. The most common description I heard was anxiety/anxious. But strong expressions like “scared”, “terrified”, and “very worried” were more common than I expected (~5-10%). About half of event professionals, and slightly less of everyone I heard, shared feeling unsettled. “Unsettled” is a mixture of fear and sadness we may feel when we experience the world as less predictable and our sense of control or comfort with our circumstances reduced.

About half of event professionals, and slightly less of everyone I heard, shared feeling unsettled. “Unsettled” is a mixture of fear and sadness we may feel when we experience the world as less predictable and our sense of control or comfort with our circumstances reduced.

I was surprised that about half of the general populace mentioned feeling some form of hopefulness about their current situation. Event professionals were far less likely to share feeling this way. This discrepancy is probably because some of the non-event industry people were retirees, and others have escaped significant professional impact.

I was surprised that about half of the general populace mentioned feeling some form of hopefulness about their current situation. Event professionals were far less likely to share feeling this way. This discrepancy is probably because some of the non-event industry people were retirees, and others have escaped significant professional impact. How I got here?

How I got here? Attending a private independent school with experienced teachers and small class sizes greatly increased my likelihood of access to higher education. On graduation, I won a second scholarship to Oxford University.

Attending a private independent school with experienced teachers and small class sizes greatly increased my likelihood of access to higher education. On graduation, I won a second scholarship to Oxford University.

What’s the most important life lesson that you wish you learned ten years earlier?

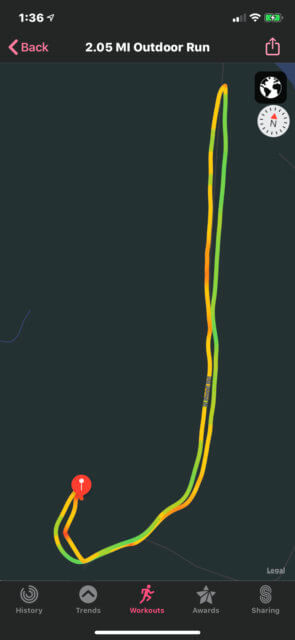

What’s the most important life lesson that you wish you learned ten years earlier? ![The first hill is the hardest: a photograph of a man running on a flat country dirt road. Photo attribution: Jenny Hill jennyhill [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.conferencesthatwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Runner_in_Stainburn_Forest-640x426.jpg)

I still remember the day, several months after I started, when I ran the whole route.

I still remember the day, several months after I started, when I ran the whole route.