A novel way to assess consensus

Chapter 44 of my book The Power of Participation explains how facilitators use participatory voting to provide public information about viewpoints in the room, paving the way for further discussion. In particular, we often use participatory voting to assess consensus.

It’s often unclear whether a group has formed a consensus around a specific viewpoint or proposed action. Consensual participatory voting techniques can quickly show whether a group has reached or is close to consensus, or wants to continue discussion.

Methods to assess consensus

For small groups, Roman voting (The Power of Participation, Chapter 46) provides a simple and effective method of assessing agreement.

However, Roman voting isn’t great for large groups, because participants can’t easily see how others have voted. Card voting (ibid, Chapter 47) works quite well for large groups, but it requires:

- procurement and distribution of card sets beforehand; and

- training participants on how to use the cards.

A novel way to assess consensus with large groups

I recently came across a novel (to me) way to explore large group consensus. This simple technique requires no training or extra resources. In addition, it’s a fine example of semi-anonymous voting: group voting where it’s difficult to determine how individuals vote without observing them during the process. [Dot voting (ibid, Chapter 49), is another semi-anonymous voting method.]

Want to know how it works?

By using humming!

Humming: a tool to assess consensus

Watch this 85-second video to see how it works.

I learned of this technique from the New York Times:

“The Internet Engineering Task Force eschews voting, and it often measures consensus by asking opposing factions of engineers to hum during meetings. The hums are then assessed by volume and ferocity. Vigorous humming, even from only a few people, could indicate strong disagreement, a sign that consensus has not yet been reached.”

—‘Master,’ ‘Slave’ and the Fight Over Offensive Terms in Computing, Kate Conger, NY Times, April 13, 2021

The Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF)is “the premier Internet standards body, developing open standards through open processes.” We all owe the IETF a debt, as they are largely responsible for creating the technical guts of the internet.

On Consensus and Humming in the IETF

The IETF builds consensus around key internet protocols, procedures, programs, and concepts and eventually publishes them as RFCs (Request for Comments). And, yes, there is a wonderful RFC 7282 On Consensus and Humming in the IETF (P. Resnick, 2014).

Software engineer Ana Ulin explains further:

‘In IETF discussions, humming is used as a way to “get a sense of the room”. Meeting attendees are asked to “hum” to indicate if they are for or against a proposal, so that the person chairing the meeting can determine if the group is close to a consensus. The goal of the group is to reach a “rough consensus”, defined as a consensus that is achieved “when all issues are addressed, but not necessarily accommodated”.’

—Ana Ulin, Rough Consensus And Group Decision Making In The IETF

When assessing rough consensus, humming allows a group to experience not only the level of agreement or disagreement but also the extent of strong opinions (like Roman voting’s up or down thumbs). And if the session leader decides to hold further discussion, the group will have an idea of who holds such opinions.

Voice voting

This technique to assess consensus reminds me of voice voting at New England Town Meetings, which have been annual events in my home state, Vermont, since 1762. But, though it’s possible to hear loud “Aye” or “Nay” votes, humming makes strong opinions easier to detect.

Conclusion

RFC 7282 starts with an aphorism expressed by Dave Clark in 1992 on how the IETF makes decisions:

“We reject: kings, presidents and voting.”

“We believe in: rough consensus and running code.”

Replace “running code” with your organization’s mission, and you may just have the core of an appealing approach to decision-making in your professional environment.

And let us know in the comments below if you try using humming as a tool to assess consensus!

Video “Please Hum Now: Decision Making at the IETF” courtesy of Niels ten Oever

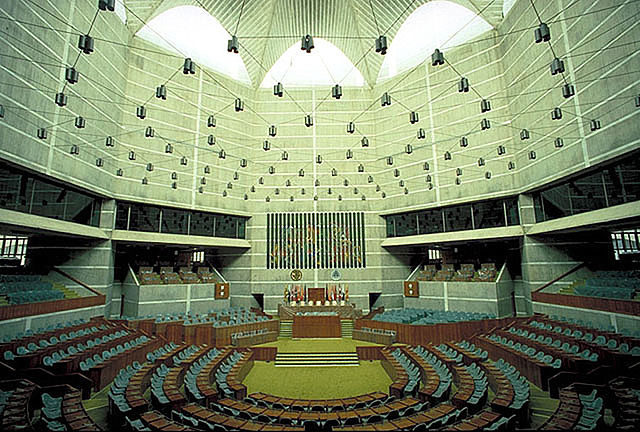

Image background by Robert Scoble