Playing games, gamification, and the gulf between them

Playing games with Bernie DeKoven

Bernie DeKoven published his classic book The Well-Played Game, (originally published in 1978) long before its time. Eventually, a generation of game designers discovered its importance and the book was reissued in 2013, five years before his death.

I was lucky enough to play games led by Bernie. I still remember my joy while playing a glorious session of the “pointless game” Prui. (Recommendation: play Prui at least once before you die. A group of people and an empty room is all you need.)

A game designer’s experience

Here’s an eloquent description of game designer and performative games artist Professor Eric Zimmerman‘s experience of playing games with Bernie in the ’60s:

“Not too long ago, I was privileged to take part in a New Games event led by Bernie. On a brisk afternoon in the Netherlands, a few dozen players stood outside in a circle. With the boundless panache of a practiced ringmaster and the eternal patience of a kindergarten teacher, Bernie taught us several games.

Bernie led by example, always reminding us that we could change the rules to suit the moment, or that we could exit the game whenever we wanted. Attuned to the spirit of the group, he flowed effortlessly from one game to another, tweaking a ruleset to make a game feel better, always somehow knowing exactly when it was time to move on.

He wove his spell. Or, rather, we wove it together. As we threw animal gestures across thin air, raced like hell with locked knees to capture enemies, and became a single blind organism with a forest of groping hands, Bernie helped us massage our play into a more beautiful shape. In a short space of time, jaded gamers, know-it-all developers, and standoffish academics became squealing, sweating, smiling purveyors of play.

‘This is amazing! I can feel the equilibrium shift and restore itself. I can’t tell which one of us is making it happen. But I feel so sensitive–I can sense the game. I can sense the way we’re playing it together. And I love it. I love being this way. I love doing this thing, playing this game with you.'”

—Eric Zimmerman, from the original Foreword to The Well-Played Game

The joy of playing

I hope it’s obvious at this point what a well-played game can be like. (Though, of course, experiencing transcends reading about a game.)

One more quote. Bernie wrote the following in 1978 about playing well:

“If I’m playing well, I am, in fact, complete. I am without purpose because all my purposes are being fulfilled. I’m doing it. I am making it. I’m succeeding. This is the reason for playing this game. This is the purpose of this game for me. The goals, the rules, everything I did to create the safety and permission I needed, were so that I could do this-so I could experience this excellence, this shared excellence of the well-played game.”

I’m hearing joy here.

Games and gamification

Merriam-Webster defines gamification as “the process of adding games or gamelike elements to something (such as a task) so as to encourage participation”.

Now, compare what you’ve just read with your experience of “gamification” of meetings.

If you’re like me, there’s no comparison between the experience of playing a game well and the experience (often negative) of participating in “gamified” conference sessions. The former is transcendent, the latter is often something to avoid.

As I wrote last week, gamification concentrates on competition and rewards to encourage participation. Proponents don’t directly address whether gamification leads to joy and fun. Instead, they imply it by including a version of the word “game”.

As game designer and author Ian Bogost put it:

“The rhetorical power of the word “gamification” is enormous, and it does precisely what the bullshitters want: it takes games—a mysterious, magical, powerful medium that has captured the attention of millions of people—and it makes them accessible in the context of contemporary business.”

—Ian Bogost, Gamification is Bullshit (2011)

Competition

Yes, competitive experiences can be fun. (Though, as I write this on the morning of Super Bowl Sunday 2020, I’m wondering how much fun the Chiefs and Buccaneer players will experience.) It turns out that including competition in a well-played game is surprisingly tricky. Bernie, who designed events and computer games in the 1970s and ’80s, wrote extensively about this, including the roles of coaches and spectators.

Rewards

Yes, rewards can be fun too, provided the rewards are, well, rewarding.

The problem is that manufactured competitive experiences usually feel fake. I’m supposed to get excited about beating some other randomly chosen team so I can win a prize I generally don’t want that much. Even if the prize is substantial — “an all-expenses paid trip to Hawaii!” — what I have to go through to “win” is unlikely to feel joyous.

And, of course, “you have to play to win.” But, as Bernie says in The Well-Played Game:

“…as I’ve seen and said so many times, if I have to play, I’m not really playing.”

Once someone requires you to “play the game”, gamification becomes little more than trying to make an obligatory task more enjoyable. Articles like this one, which touts the benefits of gamification on an already highly competitive group, are silent on the effects of a coercive learning environment on participants in general, many of whom may resent being constantly compared with their peers.

Gamification confusion

Many of the comments on last week’s post referenced using games to improve the effectiveness of learning, or adding some fun activities to an event. This is a straw man argument, because, yes, using games to achieve specific objectives, like learning something experientially or having fun is often helpful. Applied Improvisation (1, 2), about which I’ve written a fair amount, is a fine example, as are serious games. But these approaches are not gamification as it’s routinely marketed! In reality, these are game-like activities that have value in their own right, rather than band-aiding them onto existing meeting activities.

In contrast, the concept of “gamifying” something we already do at a meeting is a marketing strategy rather than something that’s useful.

Incorporating playing games well into events

Here are a couple of examples of successfully incorporating game playing, ala Bernie DeKoven, into events.

Simulations and serious games

Several years ago, I participated in a high-end business simulation during a meeting industry conference. [If anyone can provide more information on this session, please let me know!]

It included briefings and a set of high-quality videos that introduced a motorsports business situation leading to several possible choices. We split into small groups and discussed what our group thought was the best choice. We shared and discussed the group conclusions en masse and chose one of them, which led to another video segment showing the consequences and giving us another set of choices. After, I think, three choice points, the simulation ended and we debriefed and discussed the lessons learned.

The small groups didn’t create significant connection, so I wouldn’t class this as gamification, but it was a learning experience with game-like features.

I remember that creating this single example was clearly very expensive and only provided limited (though probably quite effective) learning. The session provided the same kind of experience as some interactive courseware built for education.

Applied Improvisation

Ask people what “improvisation” brings to mind, and many mention improvisation in the performing arts, aka improv. As the name suggests, applied improvisation (AI) applies improv techniques, skills, and games developed and formalized over the last hundred years to learning activities in areas like team building, social work, health care, responding to emergencies, etc. — in other words, student-centered interactive learning.

Today, AI practitioners have a rich inventory of hundreds of games, with a myriad of variations. (Some invented, as you might expect, in the moment as needed.) A skilled AI practitioner can design meeting sessions that satisfy complex needs for improved human interaction. These sessions are also a lot of fun!

The gulf between playing games and gamification

Both of the above examples require significant resources. Simulations involve careful learning design plus the creation of supporting materials. Successful AI must be led by a highly trained, skillful, and experienced practitioner.

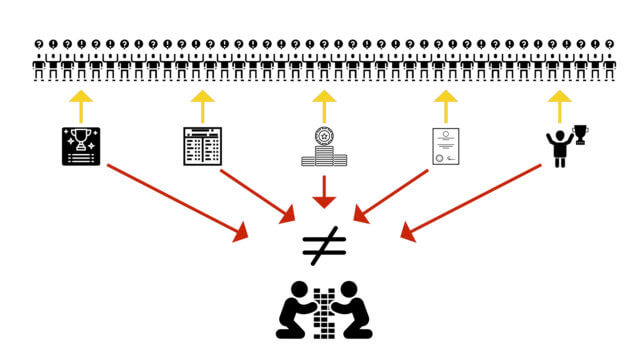

In addition, these approaches are not examples of gamification. Why? Because simulations and AI sessions are designed from the ground up to meet specific outcomes, rather than slapping achievements, badges, leader boards, and payments onto a traditional learning environment.

To conclude, incorporating playing games thoughtfully and productively into meetings is possible, and desirable. But it’s not something you can do meaningfully on a formulaic basis by adding competition and rewards, which is what proponents of gamification are selling. Caveat emptor!

Gamification “makes about as much sense as chocolate-dipped broccoli”. Education professor

Gamification “makes about as much sense as chocolate-dipped broccoli”. Education professor