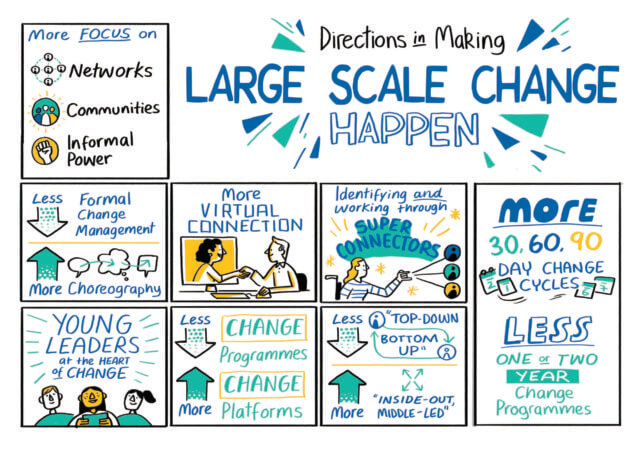

Making large scale change happen

I recently came across some principles for “making large-scale change happen“. I think they’re worth sharing.

Here’s the text version:

- More focus on networks, communities, and informal power.

- Less formal change management; more choreography.

- More virtual connection.

- Identifying and working through super connectors.

- Young leaders at the heart of change.

- Less change programs; more change platforms.

- Less top-down; more bottom-up and inside-out, middle-led.

- More 30, 60, 90-day change cycles; less one or two-year change programs.

I like and agree with all of these principles. In particular:

Number 6. focuses on creating lasting process and culture that supports and normalizes change in an organization. This is a superior approach compared to the traditional lumbering change programs that are generally irrelevant long before they are “completed”.

Number 8. emphasizes the importance of small, quick experiments. The hardest problems organizations face are chaotic and complex (the Cynefin model). Therefore, they require novel and emergent practices: experiments to learn more about how the problem areas respond to action and probes.

I have one caveat. Number 3. “more virtual connection” is certainly appropriate if it adds to the repertoire and quality of connections or reduces access privilege. But be careful not to replace important face-to-face connection opportunities with virtual ones. Until we get the holodeck, virtual doesn’t provide the quality of connection and engagement that routinely occur at well-designed face-to-face events.

How do you facilitate change? In this occasional series, we explore various aspects of facilitating individual and group change.

Image attribution: The Horizons Team at National Health Service England

We are biased against creativity. Though most people say they admire creativity, research indicates we actually prefer inside-the-box thinking.

We are biased against creativity. Though most people say they admire creativity, research indicates we actually prefer inside-the-box thinking. Almost all organization leaders today wield positional power: the power of a boss to make decisions that affect others. This is unlikely to change soon. However, the growth of the

Almost all organization leaders today wield positional power: the power of a boss to make decisions that affect others. This is unlikely to change soon. However, the growth of the  Here’s one reason I like science fiction. The other day I was rereading

Here’s one reason I like science fiction. The other day I was rereading

Do you know what happens when you stretch a rubber band? After it’s stretched, it never entirely goes back to quite the length it had before.

Do you know what happens when you stretch a rubber band? After it’s stretched, it never entirely goes back to quite the length it had before. Getting your attendees to do something new at your event can be hard. For example, Seth Godin illustrates the problem:

Getting your attendees to do something new at your event can be hard. For example, Seth Godin illustrates the problem: Is it possible to transform

Is it possible to transform