Guns and Power

I grew up in England where “access by the general public to firearms is subject to some of the strictest control measures in the world.” When I moved to the United States in 1977, I didn’t realize I had chosen to live in a country where guns and power are inextricably entwined.

I grew up in England where “access by the general public to firearms is subject to some of the strictest control measures in the world.” When I moved to the United States in 1977, I didn’t realize I had chosen to live in a country where guns and power are inextricably entwined.

I’ve only fired a gun once in my life. Hiking in former Czechoslovakia in the ’60s, I met a farmer who asked if I’d like to fire his shotgun. Standing in the middle of his field, I braced the gun against my shoulder, pointed it at the sky, and fired. The blast was deafening and my shoulder hurt.

The experience did not impress me. I had no desire ever to fire a gun again.

Guns in the United States

Although a majority of United States households don’t own guns, a substantial minority do.

Owning guns is far more common in the U.S. than in any other country; there are more guns in private hands than people to hold them. The average U.S. gun owner has five guns, and about a third of all the civilian guns in the world are in the hands of Americans.

Guns and power-over

As children, we necessarily submit to power-over: the power of our parents and school. As we grow into adulthood, most cultures expect us to become more independent and possess our own power.

Unfortunately, for a host of reasons, many people fail to come into their own power. I, for example, grew up in an environment that relentlessly shamed me for making mistakes. I learned that I could only feel powerful if I did everything perfectly. It has taken decades for me to unlearn this false teaching, and work to learn who I actually am and be myself.

When we fail to come into our own power, we fear not being in control. One way to lessen this fear is to own guns as a substitute for one’s personal power.

“…most research comparing gun owners to non-gun owners suggests that ownership is rooted in fear…

—Joseph M. Pierre, Nature, The psychology of guns: risk, fear, and motivated reasoning

In the United States, gun manufacturers who “position their products as totems of manhood and symbols of white male identity” use such fear to sell guns. Here’s an ad for the Tavor semiautomatic rifle that claims the gun will restore the “balance of power” for men who own it.

Obviously, guns have legitimate uses for hunting, and I have the privilege of living in a part of the world where it’s unlikely that someone will attack me while living my life. However, the high incidence of gun ownership by privileged U.S. citizens owes a lot to the dysfunctional fear of not being in control.

Even though the reality is that no one ever actually has control, just the myth of control.

Power and pleasure

Some people, mainly men in my experience, enjoy firing guns. When asked why they typically say it’s fun or they enjoy the challenge to get good at it (see, e.g. this Quora thread).

This challenge I kind of get. Though I think there are much more interesting and useful challenges to take on than getting better at knocking something over or blowing it apart from a distance.

It’s the fun part I don’t understand.

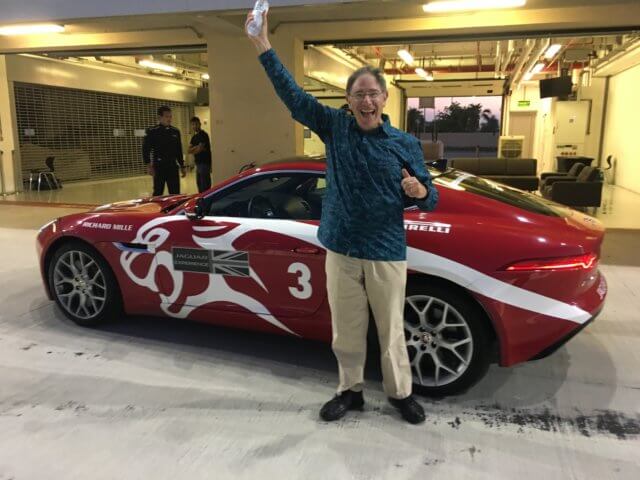

The closest I’ve come to enjoying a powerful machine is the time I drove a race car in Abu Dhabi.

Driving a race car

I had fun!

I’m cautious about trying to “explain” why driving the Jaguar for twenty minutes felt so exciting. But I think it was because my race car experience was an exaggerated version of something I do daily which is pretty miraculous — drive a car.

I couldn’t live in rural Marlboro without a car. (Here’s an account of what Vermont white settlers — who had horses at least — had to do two centuries ago to survive.) Although there are no stores in Marlboro, I can drive to nearby stores in twenty minutes. That’s a journey that in the past would have been a day’s outing in good weather. Driving is really cool.

Driving the race car took my daily driving to a whole new level. I drove faster than I’ve ever driven in my life. The race track was perfectly smooth, and the Jaguar was incredibly responsive. It wasn’t a useful experience, but it gave me a whole new and improved (sensation-wise) experience of something familiar.

Nevertheless, I have no significant desire to drive a race car again. (Though I think I’d do it if someone offered me the opportunity with no effort on my part, as happened in Abu Dhabi, that’s not likely to happen!)

Race cars versus guns

Guns are also powerful machines. But, unless you hunt for a living, there’s no analogous daily experience to shooting modern guns, which have been designed over the years to become more powerful (aka deadlier).

So why is shooting a gun “fun”? The men who say this seem to assume it’s obvious. I’ll close these musings by wondering if their desire to shoot guns arises from fear of not being in control in a United States culture that links masculinity to the wielding of power.

![The first hill is the hardest: a photograph of a man running on a flat country dirt road. Photo attribution: Jenny Hill jennyhill [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.conferencesthatwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Runner_in_Stainburn_Forest-640x426.jpg)

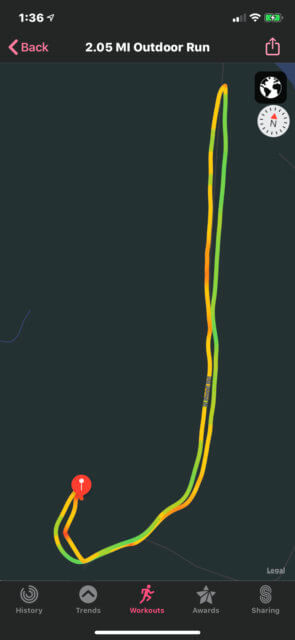

I still remember the day, several months after I started, when I ran the whole route.

I still remember the day, several months after I started, when I ran the whole route.

It’s not only the unexpected topics and activities that it turns out people want and get but also the serendipitous connections that get made. One of the things I feel best about? The lifelong friendships between seemingly unlikely souls, sparked by events I’ve had a hand in. You can’t put a price on that.

It’s not only the unexpected topics and activities that it turns out people want and get but also the serendipitous connections that get made. One of the things I feel best about? The lifelong friendships between seemingly unlikely souls, sparked by events I’ve had a hand in. You can’t put a price on that.