Air quality readings during my trip to Puerto Rico

So when I took a deep (masked) breath and decided to accept an invitation to design and lead a two-day meeting industry leadership summit in Puerto Rico, I decided to bring my CO2 meter with me. What would I learn about the air quality in the airports, planes, and ground transportation I used, as well as my hotel and the summit’s convention center? Well, I uncovered significant air quality concerns in places that may surprise you. Read on to find out what I discovered. But first, a brief explanation of what CO2 measurements mean.

How do CO2 levels correlate with the risk for COVID-19 infection?

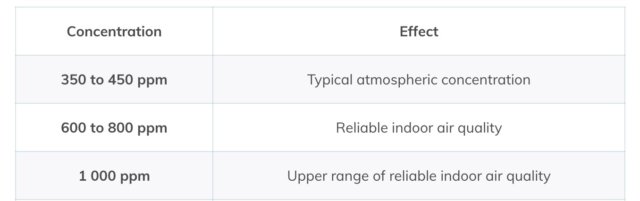

It’s complicated! Measurements of indoor CO2 concentrations can often be good indicators of airborne infection risk. But clear conclusions on the CO2 level corresponding to a given COVID-19 infection risk are currently lacking. Multiple factors influence the risk. These include exposure duration, the mixing of air in the vicinity, the exhalation volume and rate of infected individuals, and, of course, the use of masks, virus-removing air filtration, and UVC and far-UVC radiation. This article gives some idea of the complexities involved. The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) has summarized current thinking on indoor CO2. ASHRAE takes the position that “indoor CO2 concentrations do not provide an overall indication of IAQ [indoor air quality], but they can be a useful tool in IAQ assessments if users understand the limitations in these applications.”

More research is required, especially because of “the ubiquity of indoor concentrations of CO2 in excess of 1,000 [parts per million] ppm.” And ASHRAE reports that “indoor concentrations of CO2 greater than 1,000 ppm have been associated with increases in self-reported, nonspecific symptoms commonly referred to as sick building syndrome symptoms.” To summarize, currently, there is insufficient research suggesting CO2 levels that indicate a significantly increased risk for COVID-19 infection. However, many authorities have tentatively proposed maximum levels of around 1,000 ppm CO2 as guidelines.

OK, enough of this; you probably want to know what I found. Here we go!

Flying

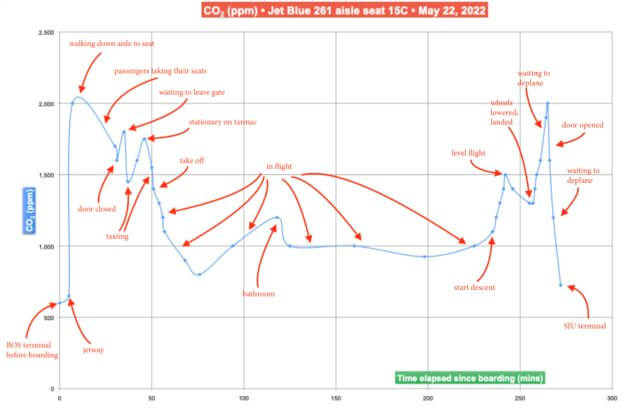

I flew JetBlue flights 261 and 462 between Boston (BOS) and San Juan (SJU). My outbound flight, on an Airbus A321, lasted 3 hours and 43 minutes. My return flight, on an Airbus A320, took 4 hours and 40 minutes. (Don’t ask.) On both flights, I had an aisle seat in row 15. As you can see from the photo at the top of this post, I perched my little CO2 meter on my knees when tray tables had to be up. The rest of the time, it nestled perfectly into the little tray table drink recess. Here’s an annotated graph of the CO2 readings I took on my outbound flight.

My key flight observations

- Boarding the aircraft led to a large spike in CO2 levels. Levels increased sharply in the jetway as I approached the passenger door. Slowly walking down a packed aisle to my seat I saw readings around 2,000 ppm. Once in my seat, the levels dropped somewhat but were still high (1,600 ppm) when they closed the door.

- Levels stayed high (above 1,500 ppm) while taxiing until we took off. We had been on the plane for about 50 minutes at this point.

- I estimate that about 30% of the passengers were unmasked, as well as most of the flight attendants.

- During the cruising portion of the flight, the CO2 level stayed at REHVA’s “upper range of reliable air quality” of 1,000 ppm. The level in the bathroom was 1,200 ppm.

- Once we started our descent, levels rose a few hundred ppm. On landing, we were at 1,300 ppm.

- During deplaning, levels soared again. I took the photo at the top of this post, showing a reading of 2,074 ppm, at this point.

- As soon as they opened the passenger door, levels dropped to around 1,200 ppm.

- On my return trip (which took close to five hours) I saw similar readings, except that:

- The cruising flight CO2 level was significantly higher (1,200 – 1,400) ppm.

- The boarding peak was lower (1,500 ppm).

- The deplaning peak was an unsettling 2,400 ppm.

To summarize, these readings are troublesome. Aircraft ventilation systems reportedly filter out aerosols, assuming that the HEPA filters are regularly replaced. However, the close proximity of passengers (both flights were full) still allows people to infect others close to them, as this NY Times article illustrates. The high readings I saw indicate that in-flight ventilation was not fully operative during embarkation and deplaning on either flight. I am glad I wore a high-quality N95 mask during both.

Airports

BOS airport levels were around 600 ppm. At SJU I saw readings between 650 – 800 ppm. Both of these are acceptable. Neither airport was especially crowded, however, and I would be cautious about assuming it’s OK to go unmasked there.

Ground Transportation

This was a shocker to me. In the U.S. during the pandemic, when driving with others I’m used to having the car windows open, at least a little. Puerto Rico was hot and humid, and the vehicles I was in had the A/C on and windows closed. My client had arranged a car and driver to pick me up from the airport and drive me to the convention center for a couple of technical rehearsals and then to my hotel. Just the two of us in a Chevy Suburban quickly raised the CO2 level to around 1,500 ppm for the 30 minutes we were together. Luckily we were both masked.

I saw the same readings during my trip to the airport at the end of the event.

But I saw the highest readings during my travel in a shuttle bus bringing us to the opening reception. There were, perhaps, 20 of us on board. Readings spiked to over 3,000 ppm! And some of the passengers were unmasked.

The conference center

The conference center was far from maximum capacity and I only saw readings well below 1,000 ppm. We held the summit in four meeting rooms with high ceilings. We left the meeting room doors open, and my meter typically showed readings between 500 – 600 ppm. If the venue had been packed or the doors closed it might have been a different story.

My hotel

I was concerned about the air quality in my (large) hotel room because I expected it to have no openable windows due to San Juan’s climate, and this proved to be the case. Over the three nights I was there I noticed the same pattern. On entering the room during the day, readings were about 600 ppm. As evening approached, the readings slowly climbed to about 900 ppm.

I had reason to be concerned.

The increase in CO2 as evening approached was probably due to increased occupancy of nearby rooms. Building heating, ventilation, and cooling (HVAC) systems typically recirculate interior air, mixing together air from all the rooms in the building. So as guests retire to their rooms in the evening, the overall CO2 concentration in every room increases.

That means that although I was alone in my room I was breathing exhalations from other guests. If any of those guests had COVID-19, it’s possible that their aerosols would travel into the air I was breathing. There was nothing I could do to protect myself other than wearing a mask the whole time I was there (which obviously included sleeping!)

Commercial HVAC systems

Commercial HVAC systems include filters to remove dust and dirt. Typical HVAC filters will not stop COVID-19 aerosols unless they have been upgraded to MERV 13 or better (e.g. HEPA). They also need to be regularly replaced to work correctly.

Whether these mitigation measures have been performed at a hotel is hard to know. My hotel was modern, but that doesn’t mean its HVAC system was well-designed and safe. I have stayed at hundreds of hotels over the years. Some of them, based on the odor of the rooms, had ventilation problems of some kind. Paradoxically, the single-unit heating and cooling systems common in inexpensive lodgings could be safer because air entering the room only comes from outside.

Concerns like these have made me cautious about staying in accommodations that don’t have windows that can be opened. That wasn’t possible in Puerto Rico, and my CO2 monitor gave me at least some reassurance that air quality levels weren’t too bad. However, many commercial lodging offerings don’t offer this option. The inspection and, if necessary, re-engineering of hotel HVAC systems is an important step to protect guest health. Yes, it costs money, but if the owners have done this work they should publicize it as a reason to stay.

For more information about this important topic, read my article about COVID-19 transmission and air quality in buildings.

Conclusion

As I write this, I’ve been isolating for four days since my return and just performed my fourth daily rapid antigen test. All have been negative. So it looks like I’ve escaped getting COVID-19 during my first major travel since the pandemic began. I recommend travelers purchase an inexpensive CO2 meter and bring it with them.

I hope the information I’ve shared in this post is helpful in warning other travelers of potentially dangerous environments. COVID-19 is far from over. As the pandemic continues, monitor your air quality while traveling—and mask up.

Travel safe!

Two-thirds of meeting planners now rank flexible meeting space as a top priority when choosing a venue, according to Destination Hotels’

Two-thirds of meeting planners now rank flexible meeting space as a top priority when choosing a venue, according to Destination Hotels’