Why presenters need to incorporate audience engagement

Why is it important for presenters to incorporate audience engagement?

“…it isn’t our schools that are failing: it is our theory of learning that is failing.”

— Douglas Thomas and John Seely Brown, authors of A New Culture of Learning: Cultivating the Imagination for a World of Constant Change.

An inconvenient truth

Think back on all the conference presentations you’ve attended. How much of what happened there do you remember?

Be honest now. I’m not going to check.

Nearly all the people to whom I’ve asked this question reply, in effect, “Not much”. This is depressing news for speakers in general, and me in particular as, since the publication of Conferences That Work: Creating Events That People Love, I have been receiving an increasing number of requests to speak at conferences.

When I ask about the most memorable presentations, people (after adjusting for the reality that memories fade as time passes) tend to mention sessions where there was a lot of interaction with the presenter and/or amidst the audience: in other words, sessions where they weren’t passive attendees but actively participated.

Take a moment to see whether that’s your experience too.

Social learning

Conference sessions that are designed to facilitate engagement between rather than broadcast content provide wonderful opportunities for social learning: the learning that occurs through connection, engagement, and conversations with our peers.

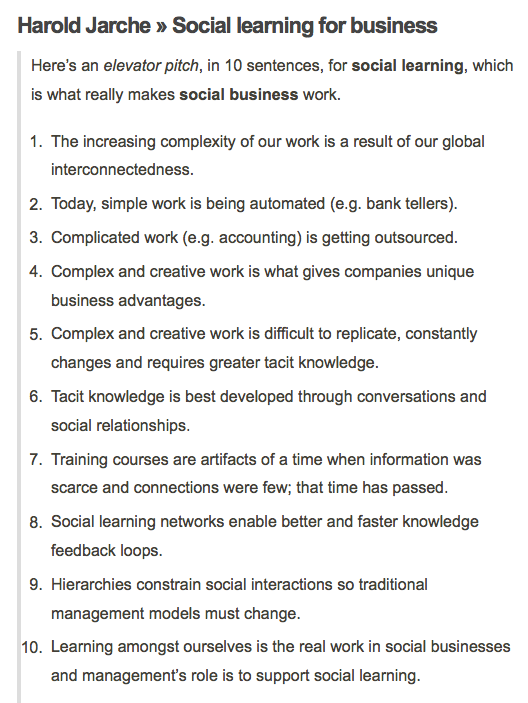

Social learning is important, and here’s why, courtesy of Harold Jarche:

There are additional reasons why supporting social learning during conference sessions makes a lot of sense:

- Active participants almost always learn and retain learning better than passive attendees.

- Participants meet and learn about each other, rather than sitting next to strangers who remain strangers during a session.

- Participants influence the content and structure of the session toward what it is they want to learn, which is often different from what a presenter expects.

- Being active during a session increases engagement, creating better learning outcomes.

- Actively participating during a session is generally a lot more fun!

A mission for conference presenters: incorporate audience engagement

Conferences provide an ideal venue for social learning; they are potentially the purest form of social learning network because we are brought together face-to-face with our peers. And yet most conference sessions, invariably promoted as the heart of every conference, squander this opportunity by clinging to the old presenter-as-broadcaster-of-wisdom model.

Of course, there are conference sessions that routinely include significant participation. Amusingly, they have a special name so they won’t be confused with “regular” conference sessions: workshops!

In my opinion, every conference session longer than a few minutes should include significant participation that supports and encourages engagement. If you’re a conference presenter, make this part of your mission—to improve your effectiveness by incorporating participation techniques into your presentations. Your audiences will thank you!

Are you a conference presenter? How much do you incorporate participation techniques into your presentations? Please share your ideas here!