Three ways to create truly surprising meetings

CoffeeGate

Two hundred people arrived for the opening breakfast at a 2015 Canadian conference to discover There Was No Coffee. The young first-time volunteer staff had forgotten to brew it.

Three days later, people were still grumbling about CoffeeGate. I bet that even today if you asked attendees what they remembered about the event, most would immediately recall the There Was No Coffee moment. A memorable moment, yes, but not a good one.

Experienced meeting planners know that every meeting has its share of unexpected surprises. While some thrive on the adrenaline rush of dealing with them, most of us work to minimize surprises by anticipating potential problems and developing appropriate just-in-case responses.

Minimizing surprises like CoffeeGate is the default behavior for meeting planners. We do not want poorly planned and/or executed events, because the inevitable result will be unhappy attendees and chaos of one kind or another.

Surprising Meetings

But not all meeting surprises are bad. Because meeting professionals want to minimize the likelihood of unexpected surprises during the execution of the events, there’s a tendency to unconsciously minimize planned surprises for the attendees. And that’s unfortunate — because planned surprises are one of the most wonderful ways we can improve attendees’ experience of the event!

Special events professionals know this. They do their best to make events surprisingly spectacular, typically focusing on food & beverage, decor, entertainment, and, occasionally, format.

In the realm of conferences and professional meetings, however, it’s easy to forget the value of surprising attendees. We’ve all been to meetings that followed the dreary welcome-presentations-meals-socials-closing remarks routine. Every minute is scheduled in advance, and attendees are told in advance everything that’s going to happen.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

To improve the attendee experience, we need to not only minimize unexpected surprises but also incorporate planned surprises into our events. And we don’t have to limit ourselves to the standard “surprising” elements that typical special events include. Here are three ways to create truly surprising meetings.

Keep the conference program secret

Each February I fly to Europe to attend the annual Meeting Design Practicum: an intense, immersive, invitation-only conference for thirty creative meeting designers.

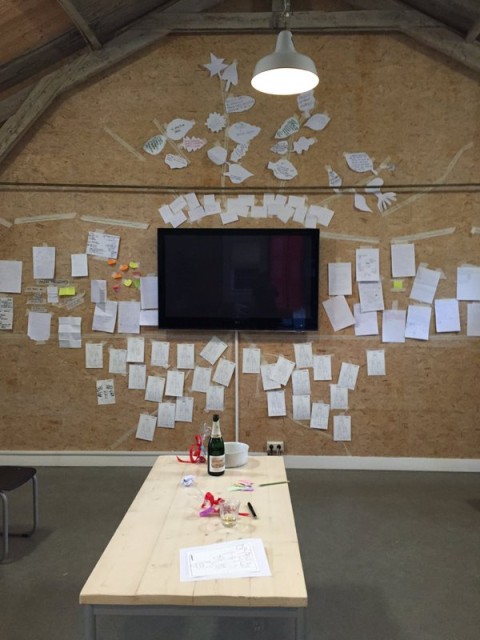

The genius of this conference is that only one person, my friend and colleague Eric de Groot, knows everything that will happen during our 48 hours together. First, Eric and his MindMeeting crew come up with a metaphor for the conference. Then they solicit individual attendees to design and facilitate (typically experimental) sessions that collectively reflect and explore the chosen frame. Participants know what they will contribute, but nothing else about the program.

For example, in 2017 we convened at a Barcelona food market. We had no idea that within a few minutes we would be partnered up and choosing exotic food items on display for our new friend to taste, let alone being whisked away in a coach an hour later to Lloret de Mar for the remainder of the conference—with the rest of the program still a mystery. As you might expect, the continuous unfolding of the entire event added greatly to participants’ enjoyment and engagement.

You probably won’t want to do this for a conventional content-focused event. But meetings where the session designs use active, interactive learning can be made far more engaging if individual presenters are prepared for their sessions but only the event organizers know everything that will occur.

Be open to surprising possibilities that appear during the event

I’ve been taking yoga classes for decades with the genial Scott Willis. Our 75-minute yoga flow is pretty standard from week to week (and for me, on balance, that’s a good thing). But yesterday, I climbed the stairs to Scott’s yoga studio and found a jar of mayonnaise on the floor. I won’t recount in detail what happened next. Suffice it to say there was general merriment for a few minutes while the origins and convoluted journey of the jar were explored and explained. A little bit of spontaneous color never hurts even a mostly predictable event. In case you were wondering, I got to bring home the jar.

Another example of being open to novel possibilities is my story of the man who brought bagpipes to my event.

[Added June 18, 2018] Traci Browne (see comments) kindly reminded me of our pleasure when we stumbled across an unexpected axe-throwing competition during a 2012 conference.

Hold sessions in metaphorical venues

Finally, we can create a genuinely surprising session by seeing what the event environment evokes. At the 2017 Meeting Design Practicum mentioned above, Manu Prina noticed a children’s playground outside our hotel, so she developed a 4-corner game played (literally!) in the sandbox! her starting point was a child’s game, with movement, simple rules, and moments of playful competition. She used it to brainstorm ideas about a problem the group was working on. The archetypal space and our memories of play as children combined to create a joyful and totally novel experience for us to work together. That’s creativity!

Make your meetings surprising — in a good way!

I hope these examples stimulate your thinking about ways to improve your event design. Besides these approaches being intuitively appealing, we also know that novel surprises stimulate learning because we are wired to notice novelty. Creating formats that surprise attendees, and in the process help them learn more effectively, is harder than, say, selecting linens. But well worth the effort!

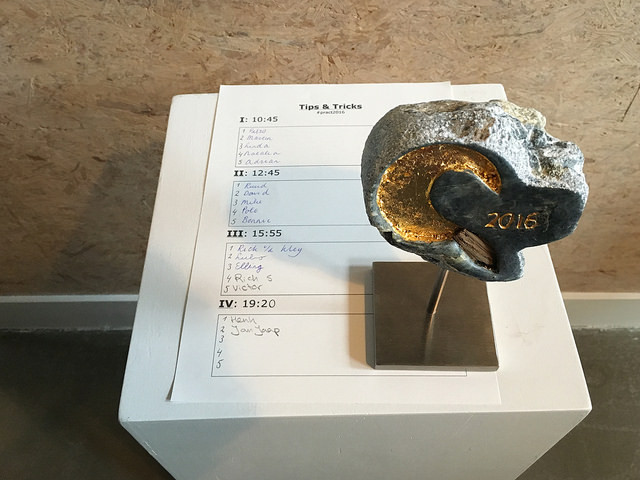

I’ve returned from a wonderful 48-hour whirlwind of experiments and play with 30 meeting designers in Utrecht, The Netherlands. We came from Europe, South America, Slovakia, and the U.S. (me) to learn, share, and connect at the first Meeting Design Practicum, hosted by Eric de Groot and his merry gang. Here are nine learnings from the first Meeting Design Practicum.

I’ve returned from a wonderful 48-hour whirlwind of experiments and play with 30 meeting designers in Utrecht, The Netherlands. We came from Europe, South America, Slovakia, and the U.S. (me) to learn, share, and connect at the first Meeting Design Practicum, hosted by Eric de Groot and his merry gang. Here are nine learnings from the first Meeting Design Practicum. I can’t give a complete survey of everything that happened at the Practicum. For one thing, I couldn’t attend every Practicum session because we often had to choose between simultaneous sessions. In addition, some of the important takeaways were already familiar to me, so I don’t include them here. Rather, I’ll share new insights that made an impression on me during our three days together. I apologize for not attributing them to specific people; suffice it to say that every single participant brought important insights and contributions to our gathering.

I can’t give a complete survey of everything that happened at the Practicum. For one thing, I couldn’t attend every Practicum session because we often had to choose between simultaneous sessions. In addition, some of the important takeaways were already familiar to me, so I don’t include them here. Rather, I’ll share new insights that made an impression on me during our three days together. I apologize for not attributing them to specific people; suffice it to say that every single participant brought important insights and contributions to our gathering.

Mom killed that idea

Mom killed that idea