Pros and cons of consulting for large organizations

Pros of consulting for large organizations

The pros of consulting for large organizations are pretty much what you’d expect.

Credibility

When choosing a consultant it’s smart to see whom they’ve worked for (and check references). Potential clients who check out my partial client list can see that I’ve worked for huge organizations like The World Bank, The Nature Conservancy, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Having had clients like these can reassure large organizations that I may be able to help them too. Smaller potential clients may also be impressed. (I also include plenty of smaller organizations on my client list, so people know I routinely work with large and small clients.)

Status

Consulting for large, well-known organizations obviously confers a certain amount of status. If you care about that kind of thing. Which some people do.

Access to resources

Large organization clients usually have more access to useful resources than smaller clients. For example, meeting rooms, specialized support staff, and travel budgets are often plentiful and generous. That can make my work easier and more pleasant. (Note: I’ve found for-profit clients have a harder time freeing up staff support for my work than the associations that make up a majority of my client mix.)

Larger fees? Perhaps…

You’d think that larger organizations would tend to pay more generous fees, and I’m sure sometimes you’d be right. However, I don’t set my fees based on the size of the client but on the scope of the work that’s needed. Though I don’t charge the stratospheric rates that some consultants quote, very small companies can have a hard time finding the money to pay me to do a good job. (And if I can’t do a good job for them, whatever the quantity of work, I won’t sign a contract.)

In general, only a few potential clients reject me because they decide they can’t afford me. My contracts with large clients may involve more time and money than similar work for a smaller client (see below). Otherwise, since I don’t set my fees on a “what the market can afford” basis, I don’t find a significant correlation between client size and fees. Other consultants’ experiences may be different.

Cons of consulting for large organizations

The cons of consulting for large organizations are less obvious than the pros. It took me a while to discover them.

More BS

In general, I don’t enjoy consulting for large clients as much as small ones. That’s because I’ve found working with large organizations involves…well, more bullshit. The BS manifests in many ways. It’s more likely, for example, that there will be conflicts between people and departments that I have to handle as part of my work. Decision-making processes are often convoluted. Administrative and contract issues take up more time.

There are exceptions. Typically they occur when I’m working for an autonomous subunit of the entire organization where the stakeholders have the decision-making authority needed for me to do my work. Under these circumstances, it’s like working for a small client, albeit one embedded in a large organization. Unfortunately, I don’t often come across this structure. Even when I do, the organization’s environment and structure sometimes warp the goals and objectives for our work in strange ways.

Harder to talk to decision-makers

One of the most frustrating issues when consulting for large organizations is that it can be impossible to talk directly with key decision-makers. In large organizations, I often work with middle managers who are enthusiastic about what we create. But then we have to sell our approach to upper management. Senior staff typically expect to hear from their middle managers rather than me. In practice, this is very inefficient. Any questions or objections that middle management can’t answer have to be passed back to me. This does not usually end well.

My rule of thumb is that if I can get ten minutes with a senior manager, we can get a go (usually) / no-go decision. For example, working with a hospital chain CEO recently, it took a few minutes to resolve an issue that no one else in the organization was able to handle. But this is frequently impossible!

I have seen more great consulting collaborations unnecessarily scuttled via the refusal of senior management to get even briefly directly involved than for any other reason.

I’m well aware that as a consultant I have no power, only influence. So I don’t take it personally when clients don’t follow my advice. But it’s still a frustrating and wasteful experience for everyone involved—and it’s a much more common outcome at large organizations.

It’s a wash

Creating long-lasting positive change in the organization

It seems plausible that a good consultant can create more long-lasting positive change in a large organization than in a small one. After all, the former has more people to influence, and any successfully introduced change will therefore affect a larger number of people.

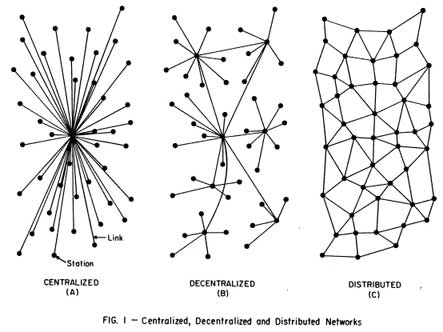

My experience tends to support Jerry Weinberg’s Law of Raspberry Jam:

Influence is like raspberry jam. The wider you spread it, the thinner it gets.

Large organizations dilute your influence for creating change because it’s spread over many people. In a small organization, I have more influence over fewer people and can help make a bigger change take place.

Here’s an example. A few years ago, I and a group of meeting designers spent a day looking into how we could improve the annual UN Climate Change Conference meeting process in order to better meet the challenges of the climate crisis. These meetings involve hundreds of countries and thousands of NGOs and people. A few hours spent reviewing the arcane procedures that have been historically used convinced me that the likelihood of a single consultant or organization affecting the outcome of these meetings was infinitesimal.

Conclusions

Personally, I prefer to consult with smaller organizations. Although the perks of working with a giant concern are rather nice, they don’t compensate for dealing with the higher level of BS that I often encounter or the increased likelihood of failing to make a positive change (despite getting paid).

I’m sure that some consultants prefer spending time in big and complex cultures. If you’re one of them and would like to share your viewpoint, please do so in the comments below. And if you agree with my preference, share that too!

Is it possible to transform

Is it possible to transform