Improve conference sessions and workshops with Color/Advance

At the workshop, the talented Patrick Short and Alan Montague reintroduced me to an improv game called Color/Advance. It’s a simple game for two players, a storyteller and a listener.

At any time while the storyteller tells a story, the listener can give either of two commands: “Color” or “Advance”. Color instructs the storyteller to describe whatever she is talking about in more detail. Advance tells her to continue with the story. Improvisors typically use the game to improve storytelling skills. They use the listener’s requests as feedback to determine when:

- More detail will spice up the story; and

- It’s time to continue with the plot.

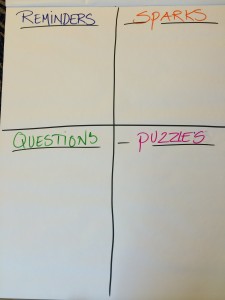

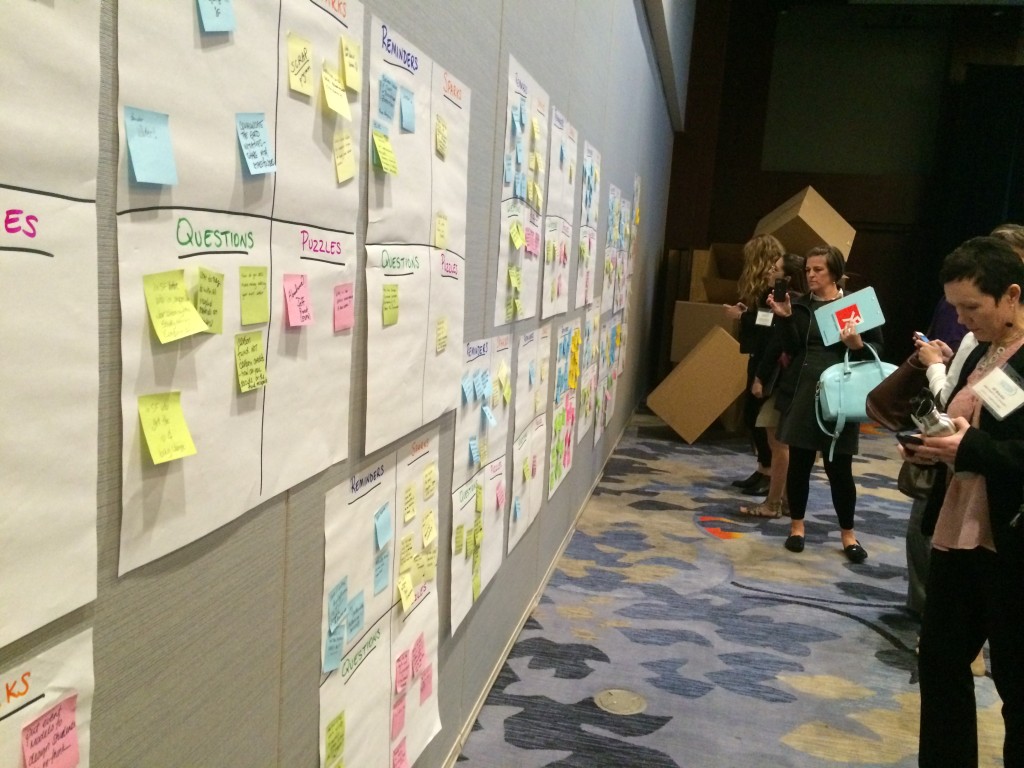

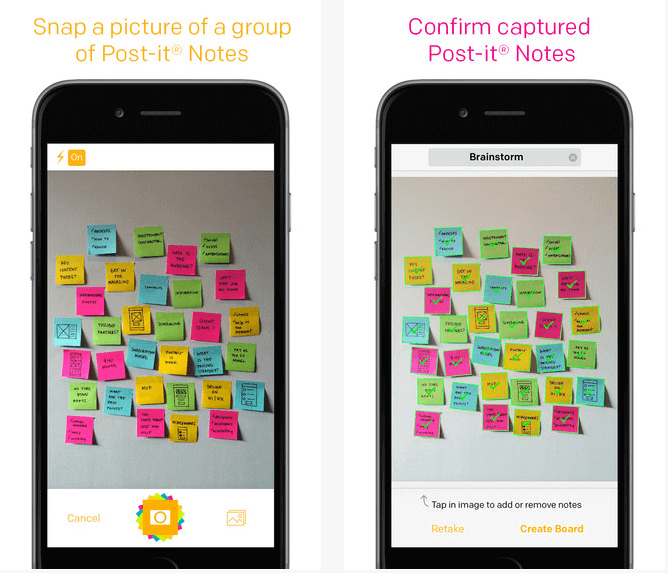

It struck me that one could use Color/Advance in a different way, as a group process tool in a conference session or workshop. Often, when I lead a meeting, I have limited information on what the participants want to get out of it. With up to about fifty participants I normally use the Post It! technique to uncover the wants and needs of the group. Then I tailor the session to fit as well as possible, covering a judiciously selected set of the topics mentioned.

This approach works very well. However there’s no standard way for attendees to indicate during the session that they would like more or less information to be shared on the current topic. It’s not unusual for people to occasionally ask for more detail. But few will spontaneously volunteer that they’ve heard quite enough about a topic and they’d like to move on to the next one.

So why not use Color/Advance as a tool for session participants to give them control over what they want to cover during a session?

Here’s what I suggest

How to use Color/Advance

After you’ve used Post It! to create an impromptu outline of the topics to include, explain that at any point anyone can say “Color!” meaning that they want more detail of what was said. Or, they can say “Advance!” which means “I’ve heard enough about this, please move on to the next topic.” Also explain that people can respectfully (and succinctly) disagree, so that the wishes of one person are not imposed on the entire group.

I love discovering how to harness human process in new ways. Body voting makes preferences and opinions public. A fishbowl allows a group to have a useful discussion. And, thanks to my experience at the AIN 2015 World Conference, we have a new tool Color/Advance for conference session or workshop participants to fine-tune the information shared to match their wants and needs.

If you have thoughts about or used this technique, please let us know in the comments!

Photo attribution: Flickr user ncindc

When facilitating,

When facilitating,