When the funeral matters more than the dead

“We live in a world where the funeral matters more than the dead, the wedding more than love and the physical rather than the intellect. We live in the container culture, which despises the content.”

–Eduardo Galeano

Sometimes we focus so intently on the form of what’s happening that we overlook the experience itself.

As an event designer and facilitator, my role is to create and lead experiences that truly meet attendees’ needs and desires. When I do this well, the design and my facilitation fade into the background. What takes center stage is each attendee’s unique experience of connection and learning. In addition, there is the possibility of creating something wonderful collectively that none of us could achieve alone

But, too often, we fetishize the form over the experience.

The structure becomes a ritual.

The ritual becomes a performance.

And the performance becomes a hollow container.

We go through the motions. We feel awe in the imposing funeral hall, yet never truly grieve. We attend a spectacular, themed destination wedding, but never feel meaningfully connected to the couple or anyone else there. We sit in uncomfortable chairs, listening dutifully to a keynote, hoping that some insight will land, but feeling no engagement, no spark, no shift.

In 2018, I asked, “What’s most important about an event, the gift or the wrapping?” It’s a question worth revisiting. Because we are mistaking the wrapping for the gift.

What happens—or doesn’t happen—for each and every person at an event is the core human reason for being there. Yes, sometimes we must attend for political, cultural, or social obligations. But is that how we want to spend our limited time on this earth? Dutifully attending events that fail to nourish, stimulate, or connect us?

What if, instead, we could experience genuine learning, meaningful connection, and a felt sense of shared humanity?

When we pour our discretionary event budget into sensory design—the elegant venue, the curated menu, the dazzling decor—yet neglect process design, we are feeding the container culture Galeano names: a culture that devalues the content.

We can do so much better.

We can design gatherings where the meaning is not just embedded in the program, but emerges from the experience. Where facilitation replaces performance. Where attendees become co-creators. Where what matters most isn’t how things look, but how people feel, change, and connect.

Form matters. But it should serve the experience, not substitute for it.

Otherwise, we’re just dressing up the silence.

If you’ve attended—or designed—an event where the content truly eclipsed the container, I’d love to hear about it. What made it work? What did it feel like?

When we commit to a future action or outcome, we also implicitly or explicitly commit to the steps required to make it happen. This typically sets us down two paths: planning and worrying.

When we commit to a future action or outcome, we also implicitly or explicitly commit to the steps required to make it happen. This typically sets us down two paths: planning and worrying. Here’s something that

Here’s something that

I get some of my best ideas from my clients. (That’s because consulting—

I get some of my best ideas from my clients. (That’s because consulting—

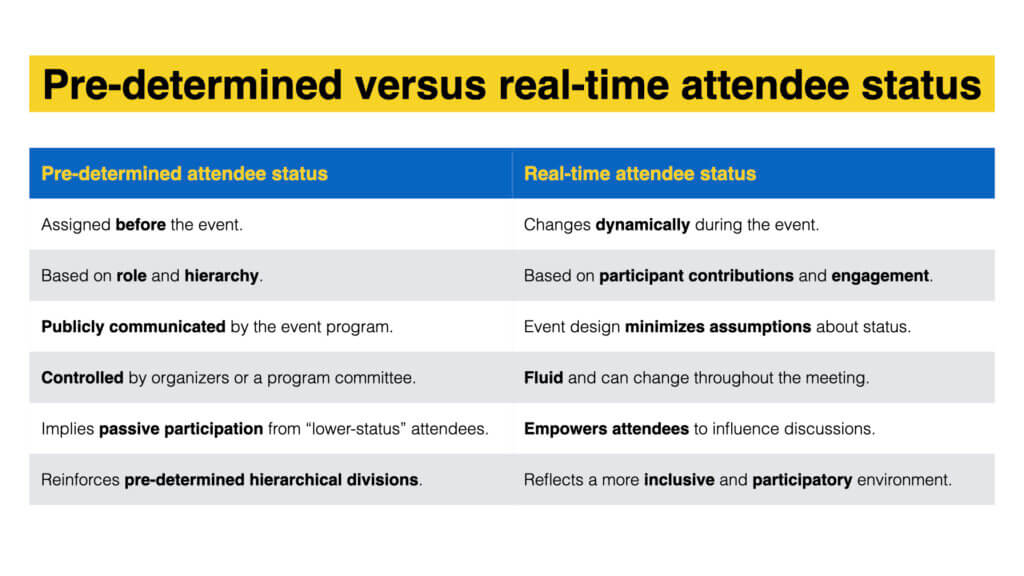

Notice that events designed to support flexible, real-time attendee status:

Notice that events designed to support flexible, real-time attendee status: