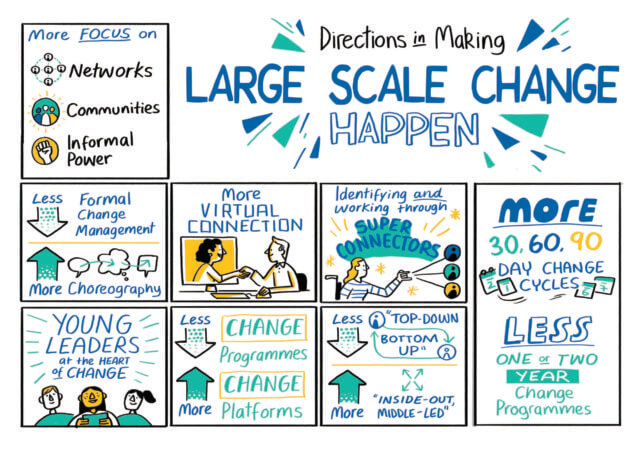

Making large scale change happen

I recently came across some principles for “making large-scale change happen“. I think they’re worth sharing.

Here’s the text version:

- More focus on networks, communities, and informal power.

- Less formal change management; more choreography.

- More virtual connection.

- Identifying and working through super connectors.

- Young leaders at the heart of change.

- Less change programs; more change platforms.

- Less top-down; more bottom-up and inside-out, middle-led.

- More 30, 60, 90-day change cycles; less one or two-year change programs.

I like and agree with all of these principles. In particular:

Number 6. focuses on creating lasting process and culture that supports and normalizes change in an organization. This is a superior approach compared to the traditional lumbering change programs that are generally irrelevant long before they are “completed”.

Number 8. emphasizes the importance of small, quick experiments. The hardest problems organizations face are chaotic and complex (the Cynefin model). Therefore, they require novel and emergent practices: experiments to learn more about how the problem areas respond to action and probes.

I have one caveat. Number 3. “more virtual connection” is certainly appropriate if it adds to the repertoire and quality of connections or reduces access privilege. But be careful not to replace important face-to-face connection opportunities with virtual ones. Until we get the holodeck, virtual doesn’t provide the quality of connection and engagement that routinely occur at well-designed face-to-face events.

How do you facilitate change? In this occasional series, we explore various aspects of facilitating individual and group change.

Image attribution: The Horizons Team at National Health Service England

Is it possible to transform

Is it possible to transform