Why I’m not deleting everything

Joan Westernberg recently wrote a post on LinkedIn that caught fire. In it, she describes deleting every trace of her productivity systems: all of her meticulously constructed “second brain”, her notes, saved articles, and to-do lists. Surprisingly, she felt relief. No panic, no regret. Just clarity.

Here’s what she wrote:

‘Every note in Obsidian. Every carefully crafted “second brain.” Every Apple Note. Every to do list.

Every article on my “read later” list.

Every productivity system I’d built over years. Gone in seconds.

And I felt zero panic. Just an overwhelming sense of relief.

Here’s what I’ve learned about our obsession with “capturing everything”:

The Promise: Build a networked archive so vast it can answer questions before you ask them. Never forget. Never lose an insight.

The Reality: My “second brain” became a mausoleum. A dusty collection of old selves, frozen curiosities, and deferred thinking.

I was reading to extract, not to understand. Listening to summarize, not to absorb. Thinking in formats I could file, not insights I could live.

This is what I know about productivity systems:

→ Storing an idea isn’t the same as understanding it → A perfectly organized system can become a prison → Sometimes the map swallows the territory

My reading database had 7,000 items. It was a shrine to the person I imagined I’d become “if only I read everything.”

But I already know what I want to read. I know the shape of my attention. I don’t need a database to prove I have taste.

What deletion taught me:

Human memory isn’t an archive – it’s associative, emotional, alive. We don’t think in folders. We think in stories, connections, experiences.

The ideas that matter will return. Not because you indexed them, because they mattered. If they don’t, they didn’t.

My new system is no system:

– Write what I think (knowing it may disappear)

– Trust that important things resurface naturally

– One simple note called “WHAT” for truly essential items (a tip I picked up from David Heinemeier Hansson)

– Read what calls to me, not what I’ve obligated myself to consumeI don’t want to manage knowledge. I want to live it.

Six years sober taught me: what got me here won’t get me where I need to be next. Sometimes the most productive thing you can do is delete everything and start fresh.’

Her post resonated with many readers, especially those who felt trapped by their own systems of digital curation. She makes a case that obsessive idea capture can become a shrine to potential, not practice. A mausoleum of “old selves, frozen curiosities, and deferred thinking”, she calls it.

I understand why this resonated. We live in an age that encourages hoarding knowledge “just in case,” and makes deletion feel almost sacrilegious. I admire her courage in pressing the reset button.

But I want to add a caveat—one rooted in the experience of a different phase of life.

Joan, you’re a lot younger than me

I’m 73. To my younger self’s surprise (and delight), I’m still doing meaningful creative work. In fact, I’d argue that much of what I do today—writing, designing participatory events, making sense of complex systems—is deeper and more insightful than what I was doing at 33 or even 53.

But here’s the difference: I no longer have the memory I once did.

When I was 25, newly minted Ph.D. in hand, I could rely on my brain to hold onto what mattered. I remembered most of what I read, heard, and thought. The shape of a complex idea, the key insight from a book I’d read two years ago, or the name of a colleague I’d encountered once at a conference—I could retrieve these easily.

That’s no longer the case.

My memory today

Today, I need external systems to support my memory. Not because I’m overwhelmed or addicted to productivity, but because I can’t trust my mind to hold onto things I suspect I’ll need later:

- A really tasty chicken recipe that I stumbled across in a sea of thousands.

- A blog post draft I wrote in 2016, containing a story that haunted me.

- A compelling idea buried in an article I saved four years ago.

- A line from a book that sparked a potential tweak for one of my facilitation methods.

These days, without some kind of archive, such ideas often disappear—not over decades, but in minutes or days.

Here’s the thing: I’m not managing these notes. They don’t clutter my attention. I’m not poring over them obsessively. I’m not trying to optimize recall or catalog my intellectual life.

I just want to be able to find what I once valued if I need it again.

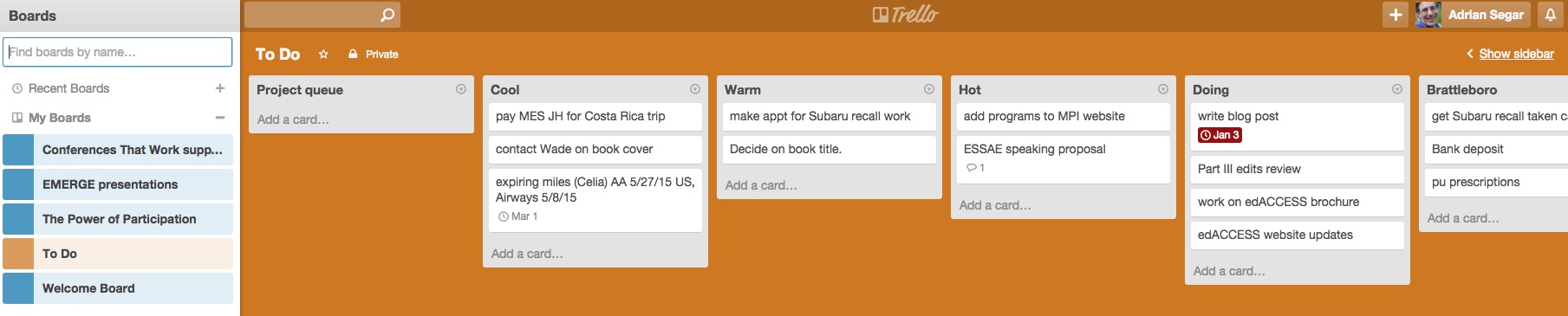

And fortunately, that’s easier than ever. Storage is cheap. Search is fast. My notes in Joplin and Apple Notes, along with well-named files and folders on my Mac, sit quietly, searchable in seconds. Ready, should a long-lost idea come knocking again.

Capturing them guards against another reality: websites rot. The online world is fragile. What you thought would always be there might vanish tomorrow.

So no—I’m not deleting everything. I’m not starting over. I’m simply acknowledging that my brain has changed, and that one of the gifts of technology is that it can help me keep creating with richness and depth, even as I forget more than I used to.

Joan’s insight that “the ideas that matter will return” is often true. But I would gently add that sometimes they return because you left a trail for them to be retrieved.

A gentle scaffolding

My system isn’t elaborate. But it’s enough.

Enough to support the creative work I still care deeply about.

Enough to help my future self rediscover what my past self found valuable.

And enough to keep me moving forward without obsessively cataloging what I’ve already done.

For some of us, there’s a season for gentle scaffolding—simple systems that hold what we can’t, so we can keep doing the work that still matters.

When we commit to a future action or outcome, we also implicitly or explicitly commit to the steps required to make it happen. This typically sets us down two paths: planning and worrying.

When we commit to a future action or outcome, we also implicitly or explicitly commit to the steps required to make it happen. This typically sets us down two paths: planning and worrying.

Recently, I had a thought-provoking conversation with association maven and friend

Recently, I had a thought-provoking conversation with association maven and friend  How to work with others to change our lives

How to work with others to change our lives We spend too much time distracting ourselves from what matters.

We spend too much time distracting ourselves from what matters.

I was hanging out at the

I was hanging out at the  I’ve replaced my treadmill desk with the next generation: a simpler, cheaper, and better alternative!

I’ve replaced my treadmill desk with the next generation: a simpler, cheaper, and better alternative!

How can we get better at doing anything?

How can we get better at doing anything?