Seating while Eating at Meetings

It’s no Comedians in Cars getting Coffee, but here’s my draft script for Seating while Eating at Meetings. Let’s start with…

It’s no Comedians in Cars getting Coffee, but here’s my draft script for Seating while Eating at Meetings. Let’s start with…

Three criteria for good seating while eating

- Maximal intimacy. This is the big one. When I’m eating at a meeting I want to, well, meet people. I can eat alone any time, thank you very much. And if I want to converse with one or two other people, just about any seating configuration will work. But if I’m with five best friends, I want to be able to communicate with them without shouting or straining to hear them. And when banqueting strangers surround me, I’d like to maximize the number of new people I can effectively meet.

- Lack of distractions. I can’t meet other people when our conversation is drowned out by emcees, dinner speakers, or (aargh!) “mood” music. Or when a sponsor is displaying a promo movie on every wall in the room.

- Comfort. Please don’t make me sit on a cheap plastic chair or a wooden bench with no back support for an extended period while I nosh. It’s cruel and unusual punishment. (Meeting planners usually get this one right.) And if it’s too hot or cold, I’ll be miserable. If we’re going to be dining outside in the Sahara or the Arctic (cool!), let me know in advance so I can dress appropriately.

OK, got that? It’s time for a couple of specific suggestions.

Are you Tortured by Nights of the Round Table?

I am. The above link goes into detail, but from my audiologist-swears-my-hearing’s-normal-but-I-don’t-think-so perspective, traditional large rounds for seated meals — a staple of every meeting planner’s banquet design — conflict with criterion #1.

Typically, meals are served at 60″ rounds (eight seats per table), 66″ rounds (nine seats per table), or 72″ rounds (ten seats per table). I start having a hard time hearing everyone at 60″ rounds, and the larger sizes pretty much relegate me to talking with the two people on either side of me (and that’s assuming the table is full — often not the case with unassigned seating.)

If you’re going to use rounds, in my view, smaller ones are better. The problem is that many venues don’t stock them, so you may have to pay extra to use them. Nevertheless, consider using 54″ rounds (7 – 8 seats), 48″ rounds (6 seats), [or even 36″ rounds (4 seats) if your meal service isn’t super-formal]. Everyone is likely to be able to converse with everyone else at the table and maximal intimacy is yours!

The Fable of the Communal Table

Until relatively recently, most public dining occurred communally because only the rich could afford private dining rooms and there were far more poor folks around. Then we got hoity-toity and invented restaurants and conferences.

About ten years ago, communal tables started creeping back into restaurants. Some argued that this trend met a desire to return to a dining environment with greater “community”. The more cynical noted that establishments could now cram more people in the same space by seating them at long rectangular tables next to strangers.

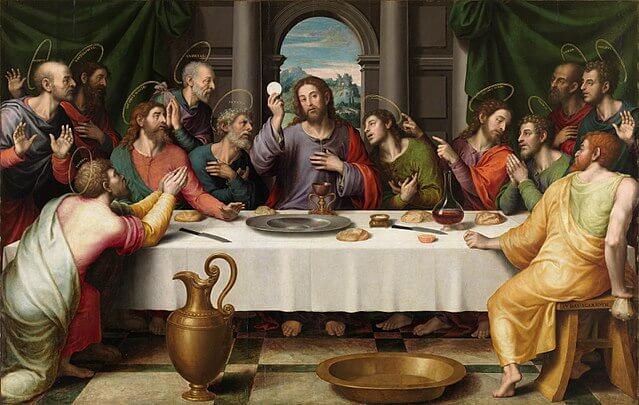

While I think communal tables are great if they’re an integral part of an authentic cultural meal where dining involves lots of moving about — e.g. as pictured below, the deliciously messy outdoor calçotada I enjoyed in Catalonia last year — at traditional conferences they are poor places to converse with others.

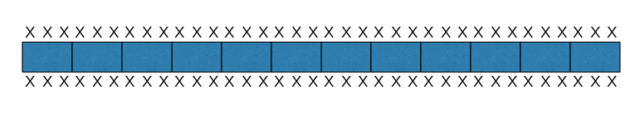

So, if you’re using rectangular tables, don’t do this:

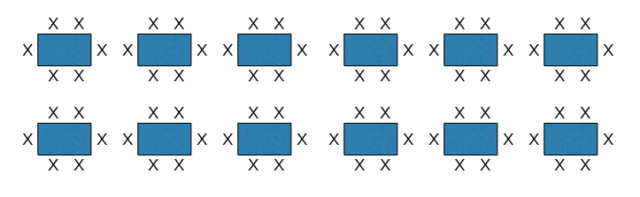

Instead, do this:

But wait, there’s more…

Sorry, I’ll admit that this is not everything you need to know about seating while eating at meetings. But it’s a start, and, like Jude, you can make it better. Please feel free to add your contributions in a comment below.

Picture of Jesus with the Eucharist at the Last Supper by Juan de Juanes – [2], Public Domain, Link

calçotada image by David Benitez

While stuck in cramped seats during a six-hour Boston to San Francisco flight, my wife gently pointed out that I had become quite grumpy. She helped me notice that my lack of body comfort was affecting my mood. Luckily for me, Celia remained solicitous and supportive, reducing my grouchiness. Once we were off the plane my spirits lightened further.

While stuck in cramped seats during a six-hour Boston to San Francisco flight, my wife gently pointed out that I had become quite grumpy. She helped me notice that my lack of body comfort was affecting my mood. Luckily for me, Celia remained solicitous and supportive, reducing my grouchiness. Once we were off the plane my spirits lightened further.