Knowing what you’re going to draw

Do you know what to draw? Perhaps — if someone has told you to draw it.

Do you know what you’re going to draw? That’s a different question. It implies that you have some agency to draw what and how you like.

Beginning creation

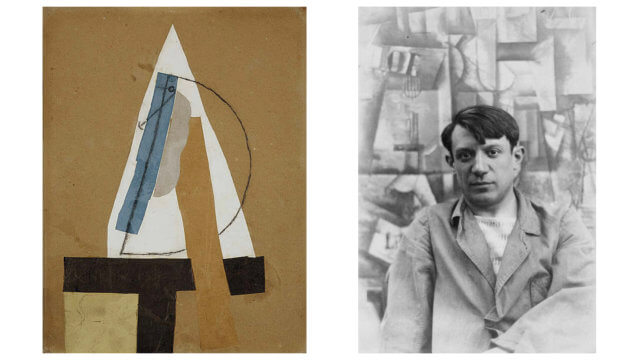

Picasso answered the second question like this:

“To know what you’re going to draw, you have to begin drawing.” —Pablo Picasso, Conversations with Picasso by Brassaï

Creating anything, there’s a moment when you begin. Picasso is saying you begin without having a completely predetermined plan of what you’re going to create and the process you will use.

This doesn’t just apply to creating what we think of as art.

Programming machines

For a quarter of a century, I wrote computer software. In that time I wrote and maintained around a million lines of code. Initially, I never thought of what I was doing as creative. I was writing instructions for a machine to process. The machine did exactly what I told it to do. How creative could that be?

My first inkling that programming might be creative came when I began teaching it. When the introductory class started, I gave students homework problems that needed perhaps ten lines of code to solve. To my surprise, I discovered that each student wrote a slightly different program. What’s more, within a few weeks I could look at one of their pieces of code and know who had written it.

As the problems got harder, it became clear that some students were more creative programmers than others.

This made me think about my own programs. I realized that I was doing creative work. Many of the programs I wrote for clients solved problems in ways that I had not foreseen when I started.

Continuing creation

Another way to look at creating something is explored in my post Process, not product. All too often, we focus on a desired finished product, rather than the moment-by-moment process of creation. This is typical when we perform mundane tasks. Needing chopped onions for a vegetable stew, we automatically slice them, one more task on the list. The mindful person is one with the chopping — they “chop wood, carry water” [XinXin Ming].

Closing creation

Finally, there is a moment when you finish creating something. Let’s be clear; creating something requires ending its creation. Billions of pages of never finished novels attest to this. Those novels never saw the light of day.

So, when do you know that something is finished? Before that moment, it was almost impossible to predict! Afterward, especially if it was a big task like writing one of my books, you may remember the moment. But don’t reinterpret that memory as something planned.

Creating something is much more mysterious than that.

Images attribution:

By <a href="//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pablo_Picasso" title="Pablo Picasso">Pablo Picasso</a> - <a rel="nofollow" class="external text" href="http://www.nationalgalleries.org/collection/artists-a-z/P/2628/artist_name/Pablo%20Picasso/record_id/2224">National Galleries, Edinburgh</a>, PD-US, Link

By <span lang="en">Anonymous</span> - <a rel="nofollow" class="external text" href="https://www.photo.rmn.fr/archive/98-021978-2C6NU0XWEWEW.html">RMN-Grand Palais</a>, Public Domain, Link

No one knew how to “teach programming” to fifteen-year-old kids then. Our teachers just handed us an

No one knew how to “teach programming” to fifteen-year-old kids then. Our teachers just handed us an