Four important truths about conference evaluations

I don’t know any meeting planners who especially enjoy creating, soliciting, and analyzing conference evaluations. It’s tempting to see them as a necessary evil, a checklist item to be completed so you can show you’ve attempted to obtain attendee feedback. Clients are often unclear about their desired evaluation learning outcomes, which doesn’t make the task any easier. After the event you’re usually exhausted, so it’s hard to summon the energy to delve into detailed analysis. And response rates are typically low, so who knows whether the answers you receive are representative anyway?

Given all this, how important are conference evaluations? I think they’re very important—if you design them well, work hard to get a good response rate, learn from them, and integrate what you’ve learned into improving your next event. Here are four important truths about conference evaluations, illustrated via my edACCESS post-conference evaluation review:

1) Conference evaluations provide vital information for improvement

We’ve held 30 edACCESS annual conferences. You’d think that maybe by now we have a tried and true conference design and implementation down cold. Not so! Even after 29 years, we continue to improve an already stellar event (“stellar” based on—what else?—many years of great participant evaluations). And the post-event evaluations are a key part of our continual process improvement. How do we do this?

We use a proven method to obtain great participant evaluation response rates.

We think about what we want to learn about participants’ experience and design an evaluation that provides us the information we need. Besides the usual evaluation questions that rate every session and ask general information about event logistics, we ask a number of additional questions that zero in on the good and bad aspects of the conference experience. We also ask first-time attendees a few additional questions to learn about their experience joining our conference community.

We provide a detailed report of post-conference evaluations to the entire edACCESS community—not only the current year’s participants but also anyone who has ever attended one of our conferences and/or joined our listserv. The responses are anonymized and include rating summaries, every individual comment on every session, and all comments on a host of conference questions.

Providing this kind of transparency is a powerful way to build a better conference and an engaged conference community. Sharing participants’ perceptions of the good, the bad, and the ugly of your event says a lot about your willingness to listen, and makes it easy for everyone to see the variety of viewpoints about event perceptions (see below).

The conference organizers review the evaluations and agree on changes to be implemented at the next conference. Some of the changes are significant: changing the length of the event, replacing some plenaries with breakouts, etc., while some are minor process or logistical tweaks that improve the conference experience in small but significant ways.

Evaluations often contain interesting and creative ideas that the steering committee likes and decides to implement. All major changes are considered experiments rather than permanent, to be reviewed after the next event, and are announced to the community well in advance.

We evaluate our evaluations. Are we asking a question that gets few responses or vague answers that don’t provide much useful information? If so, perhaps we should rephrase it, tighten it up, or remove the question altogether. Are there things we’d like to know that we’re not learning from the evaluation? Let’s craft a question or two that will give us some answers.

Using the above process yields fresh feedback and ideas that help us make each succeeding conference better.

One final point. Even if you’re running a one-off event, participant evaluations will invariably help you improve your execution of future events. So, don’t skip evaluations for one-time events—they offer you a great opportunity to upgrade your implementation skills. And, who knows, perhaps that one-off event will turn into an annual engagement!

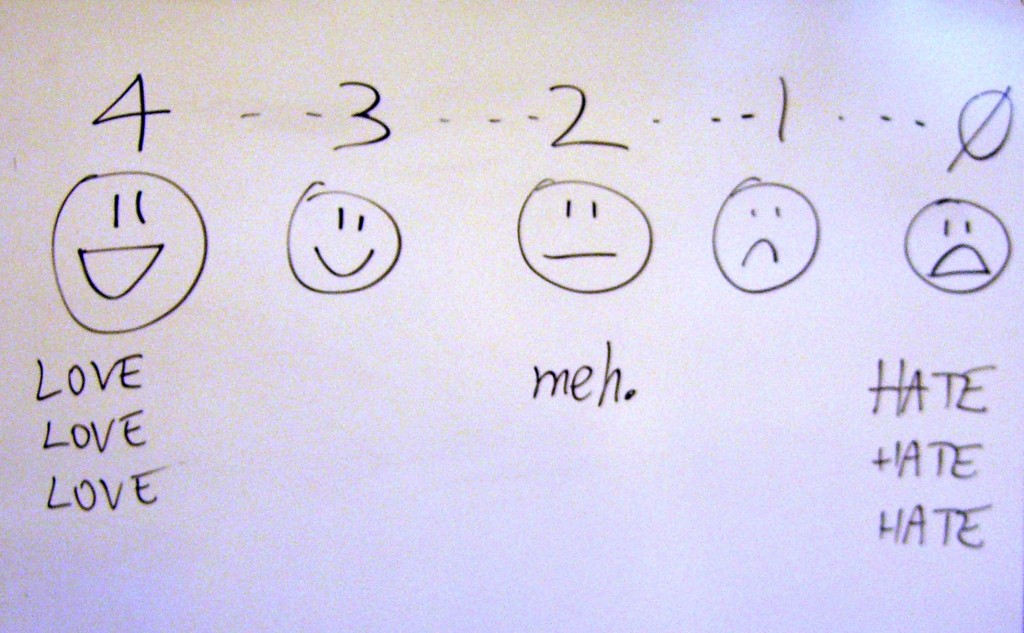

2) You can’t please everyone

“Were these people really at the same event?” Most meeting organizers have had the experience of reading wildly different evaluations of the same session or conference. While edACCESS 2013 evaluations don’t supply great examples of this, I always scan the answers to questions about the most and least useful session topics.

What I want to see is a wide variety of answers that cover most or all of the sessions. Because edACCESS is a peer conference with (at most) one conventional plenary session, I see such answers as reflecting the broad range of participant interests at the event. It’s good to know that most if not all of the chosen sessions satisfied the needs of some attendees. If many people found a specific session the least useful, that’s good information to have for future events, though it’s important to review this session’s evaluations to discover why it was unpopular.

What’s equally important is to share the diversity of the answers to these questions with participants. When people understand that a session they disliked was found to be useful by other participants, you’re less likely to need to field strident but minority calls for change—and have information to judge such requests if they do occur.

3) Dealing with unpleasant truths will strengthen your event

edACCESS evaluations contain many appreciations and positive comments on the conference format and how we run it. Sometimes, there are also a few anonymous comments that are less than flattering about an aspect of my facilitation style.

Even if the latter express a minority opinion, I work to improve from the feedback I receive. I plan to check in with the event organizing committee to get their take on the feedback. I’ll ask for suggestions on whether/how to make it less of an issue in the future without compromising the event.

Facing and learning from criticism is hard. The first response to criticism of anyone who is trying to do a good job is usually defensive. But when we confront unpleasant truths, plan to better understand them, and follow through we lay the ground for making our event and our contributions to it better.

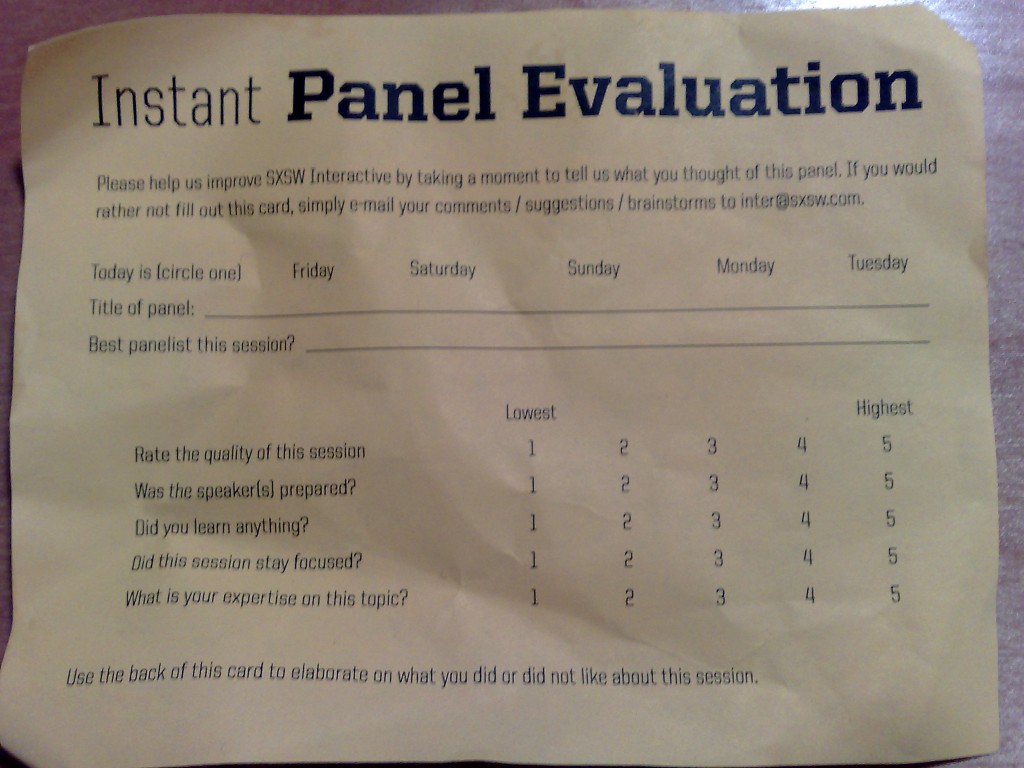

4) Public evaluation during the conference augments post-event evaluations

While it’s still rare at traditional conferences to spend time evaluating the event face-to-face, I include such a session—the Group Spective—at the close of all Conferences That Work. I strongly recommend a closing conference session that includes facilitated public discussion of the conference covering topics like What worked? What can we improve? What initiatives might we want to explore? and Next steps.

It’s always interesting to compare the initiatives brought up by this session with suggestions contained in the post-event evaluations. You’ll find ideas triggered by the discussion during the spective that may appear or may be absent from the evaluations. The spective informs and augments post-event evaluations. Some of the ideas expressed will lead to future initiatives for the community or new directions for the conference.

What experience do you have with conference evaluations, either as a respondent or a designer? What other truths have you learned about conference evaluations?

Photo attribution: Flickr user stoweboyd

Here’s a simple challenge to anyone who organizes an event and asks for evaluations.

Here’s a simple challenge to anyone who organizes an event and asks for evaluations.