We are all Donald Rumsfeld

In a Pentagon news conference on Feb. 12, 2002, United States Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld gave a now-famous response to a question about the lack of evidence linking the government of Iraq with the supply of weapons of mass destruction to terrorist groups:

“…as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say, we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don’t know.”

—Donald Rumsfeld, “There are unknown unknowns.”

For full context, here’s the whole exchange. Though it has been widely criticized as an evasive non-answer to an important question, Rumsfeld thought highly enough of his remark that he borrowed from it for the title of his controversial memoir, Known and Unknown.

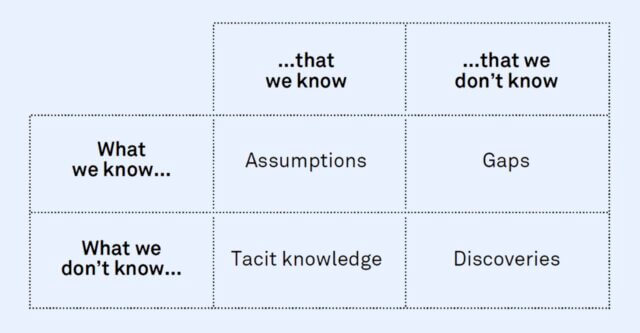

Rumsfeld’s remark includes three of the four boxes of what’s often called the Rumsfeld matrix, which pops up in all kinds of fields, such as the epistemology of knowledge, risk assessment, project management, strategic planning, and, as illustrated below, creative design.

A different take on the Rumsfeld matrix

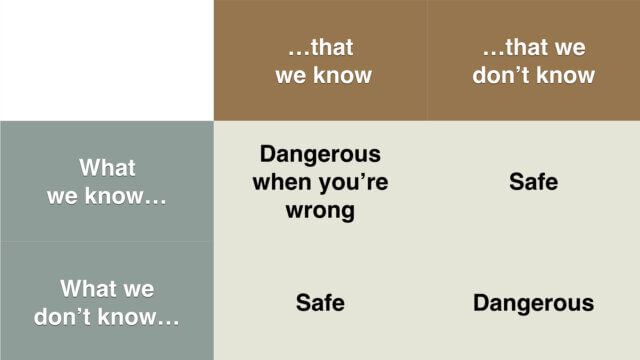

All of the examples above apply the Rumsfeld matrix to explore different kinds of analysis. What no one discusses, as far as I know(!), are the potential pitfalls of Rumsfeld’s categories. So, my take on the Rumsfeld matrix is—what if you’re wrong? Here are the consequences of incorrectly assigning one’s belief about one’s knowledge to the wrong box.

What you know you know

It’s great to know what you know. Until you’re wrong, either because you don’t actually know what you think you know, or because what you “know” is wrong.

Because everyone makes mistakes. I’m sometimes wrong about what I think I know, and since you’re probably, like me, not perfect you are too.

For example, I tell a client that I know how to do something, and then when they ask me to do it I discover that I can’t. Or, I confidently give incorrect advice.

This is obviously dangerous. Misplaced confidence in one’s knowledge has caused countless tragedies. We have a word for this: hubris.

What you know you don’t know

There are times when you’re wrong about knowing that you don’t know. Sometimes it turns out that, when the chips are down, you do know! (See the next section below.)

For example, fifty years ago I had four years of French classes in school and have barely used it since. My French is terrible. Nevertheless, every once in a while, the French word for something I would have sworn I didn’t know just pops into my head.

The good news is that believing that you don’t know something that you actually do is not dangerous. Underestimating your abilities is, at most, mildly embarrassing.

What you don’t know you know

This is the matrix box that Rumsfeld didn’t mention, though he refers to it in his memoir. Surprisingly, there’s a lot of stuff you don’t know that you know! In fact, there are probably more things that you don’t know you know than things you know you know! (I’ll wait while you figure out that sentence.) This box is about tacit knowledge, which I wrote about here.

For example, I never learned to touch type. If you asked me to list the QWERTY keyboard layout I’ve been typing on for fifty years, I’d have a hard time deriving it from memory. Despite this, I can type with three or four fingers far faster than the hunt and peck I used for the first few months on a typewriter.

Tacit knowledge is a bonus. It’s not dangerous. Thank goodness for that!

What you don’t know you don’t know

Finally, we get to the most dangerous region of the Rumsfeld matrix. When we are born, we don’t know what we don’t know. And we’re helpless, completely reliant on other humans for our survival. Slowly we pick up knowledge, making discoveries constantly. But there are always things we don’t know that we don’t know. They bedevil us our whole lives. This has been true for every culture throughout history, including ours right now.

By definition, I can’t give you a current example of what I don’t know I don’t know! That’s what makes this box so dangerous. But we can extrapolate from the past. For example, look at the history of our beliefs about what causes illness. Cultures believed that illness was caused by evil spirits and gods, or an excess of blood in the body. Today, these are rare beliefs.

In 1968, Stewart Brand wrote on the title page of his first Whole Earth Catalog, “We are as gods and might as well get good at it.” In my opinion, he was wrong, though on the back page of the final Catalog he wrote, “Stay Hungry, Stay Foolish“, which I see as a partial repudiation. What we can learn from this box is that, as Shakespeare has Hamlet say, “There are more things in Heaven and Earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” We need to remember that we don’t know all the right answers; we don’t even know all the right questions!

In other words, we need to remain humble in the face of a universe that has not shared all its secrets.

We are all Donald Rumsfeld

We are all Donald Rumsfeld. We are all susceptible to hubris and overlooking how little we actually know in the likely scheme of things. If we strive to avoid hubris and stay humble, our world will be a better place.

Image attribution: www.team-consulting.com