Two powerful ways to open a conference

If we’re creating conferences primarily for the benefit of attendees, rather than organizers/sponsors/presenters/etc.—yes, I know, it’s a radical concept—what are good things to do during the opening after the customary welcome and housekeeping? Although the answer depends on conference scope, desired outcomes, group composition, time available, and so on there are two approaches I find especially useful. (My books cover these and several other openings in detail.)

After agreeing on ground rules—essential in my view before doing group work—here’s an outline of two techniques I use extensively:

The Three Questions

Three questions:

- “How did I get here?”

- “What do I want to have happen?”

- “What expertise or experience do I have that others here might find useful?”

are printed on a large card given to each person. I explain that they cannot answer these questions incorrectly, share some examples of answers, allow participants a few minutes to answer them in writing on their cards, and then give everyone in turn the same amount of time to share their answers with the group. You can run The Three Questions in small groups, or with as many as 60 people in a roundtable. For large groups, it’s important to break up the sharing every 20 minutes. Run activities at each break that help group members learn more about the group.

The Three Questions make a clean break with the convention that at conferences most people listen and few speak. They publicly uncover a rich stew of ideas, themes, desires, and questions that are bubbling in peoples’ minds. And they expose the collective resources of the group—the expertise and experience that may be brought to bear on the concerns and issues that have been expressed.

(Want to learn more and can’t wait for my new book? My book Event Crowdsourcing has all the details you’ll need to run The Three Questions at your next event.)

The Solution Room

The Solution Room is an opening conference session, typically lasting between 90 and 120 minutes. It both engages and connects participants and provides peer-supported advice on their most pressing challenges. By facilitating peer interaction and consultation at the start of an event, The Solution Room creates a conference environment that embodies participation, peer learning, and targeted problem-solving. By the end of the session, every participant has had the opportunity to receive advice and support on a challenge of their choosing.

A session of 20 or more people starts with a short introduction, followed by a human spectrogram that demonstrates the amount of experience available in the room. Next, we give participants some time to think of a challenge for which they would like peer advice. A second human spectrogram follows which maps participants’ comfort level.

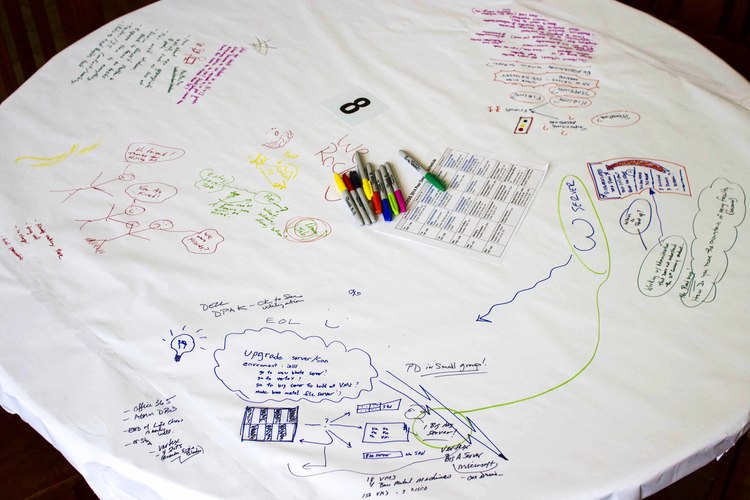

Participants are then divided into small equally-sized groups of between six and eight people. Each group shares a round table covered with flip chart paper and plenty of colored markers. Group members then individually describe their challenge on the paper in front of them using mindmapping. Each participant gets equal time to explain their issue and receive advice and support from their table peers.

When sharing is complete, two final human spectrograms close the session. They provide a public group evaluation that maps the shift in the comfort level of all the participants and the likelihood that participants will work to change what they’ve just shared.

Try ’em!

Both of these two powerful ways to open a conference allow people to learn about each other and connect around issues that are personally/professionally meaningful. In my experience, they lead to much more powerful and authentic participant engagement than the generic “icebreakers” (hate that term!) typically used.